Predictions about complex issues such as U.S. national security and future wars are difficult to reconcile with reality. If the predictions are wrong and war does break out, it will be even bloodier and more brutal, and the consequences will be catastrophic. In the vast majority of cases, it will be U.S. soldiers and Marines who will pay the heavy price.

As the international security environment changes rapidly, it is increasingly necessary to prepare for the future. The 2018 version of the National Defense Strategy (NDS) marked a fundamental shift in the U.S. security focus to strategic competition with China and Russia: the 2022 version of the National Defense Strategy retains the core principles of the previous version: China is seen as a "step-by-step challenge" and Russia only poses a "serious threat" (because its attack on Ukraine has undermined the European and international security environment).

Although both versions of the National Defense Strategy have received broad support from both Democrats and Republicans, their recommended defense budgets are seriously "out of touch" with demand. The U.S. defense budget in recent years has been based on the prediction that the great improvement of defense capabilities such as space, cyber, and anti-access/area denial (A2/AD) is reducing the possibility of large-scale, all-domain operations. According to this view, the next war will likely include "missile-centric operations, primarily in the air and sea domains; with little demand for ground forces beyond land-based long-range firepower, force protection, and logistical support/security.

This paper makes assessments and forecasts by analyzing data on wars the United States has participated in since World War II and current force requirements, and then compares these data with defense budgets, army force requirements, and army modernization funding in recent years. The Russian-Ukrainian conflict provides relevant context for this analysis, and gives us (Editor’s Note: referring to the US military) a preliminary (albeit incomplete) understanding of modern large-scale conflicts at a time when the United States is concerned about potential emergencies in the Taiwan Strait. Ultimately, the analysis identifies "three key findings" and links them to "three key recommendations."

"Three key findings" and "three key recommendations"

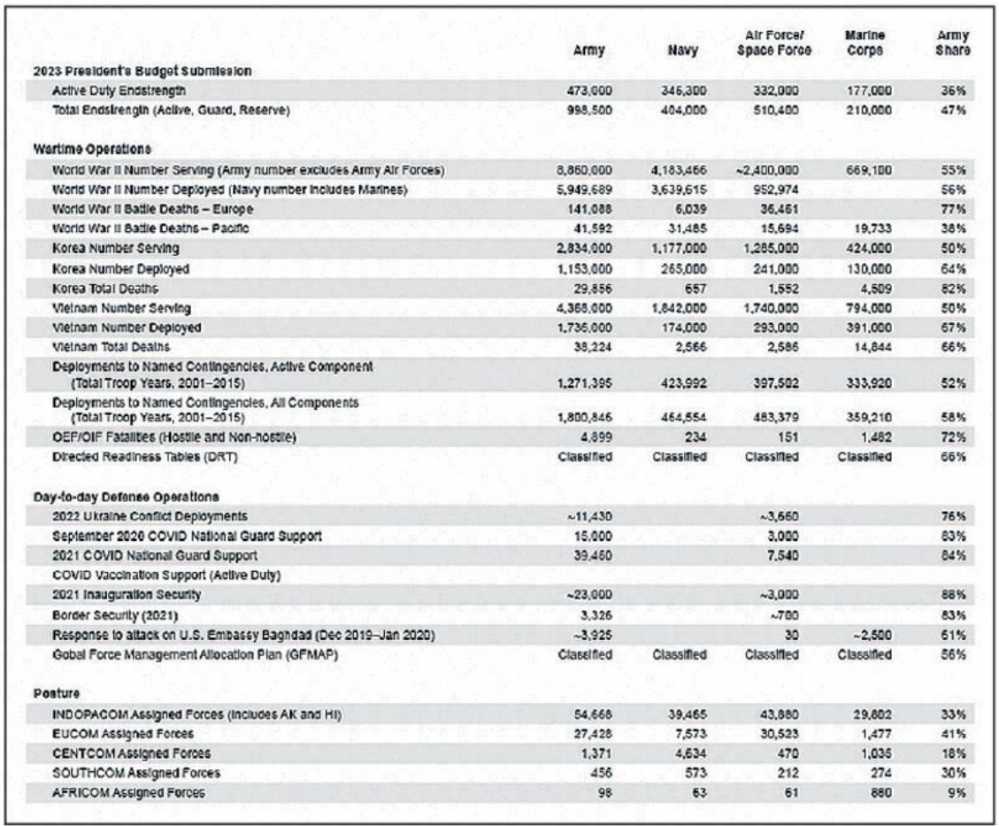

Finding One, from history The Army, which is the core of the Department of Defense’s actions in both wartime and peacetime, is now in danger of being stretched. Over the past 80 years, the Army has played a leading role in combat operations whenever the United States has gone to war. From World War II to Korea, Vietnam, and the Iraq and Afghanistan wars, the service has been deployed in about 60% of the wars, with an average of about 50% of the total number of troops involved in the war, and an average of about 70% of the wartime deaths.

However, the Army is also the backbone of the United States’ joint forces. "I use the word ’key’ because the Army has actually been the combat force that combines the joint force with key command and control capabilities, key logistics support/support capabilities, and other ’enablers’ (such as base defense, transportation, and engineering construction, etc.)," said Joe Dunford, former chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, in calling the service "key" to combat operations. ”

What is not well known is that this is also true in peacetime. Although the U.S. Army has less than 50% of the total strength of all military services, it has provided 75% of joint force support to Ukraine, 80% of the National Guard’s response to the new crown epidemic, 80% of domestic border security support operations, completed two-thirds of the combat readiness missions required by the Joint Staff, and provided more than half of the global needs of combat commands.

Despite the increasing pressure on the Army, President Biden’s 2023 defense budget cuts its funding to the lowest level since 1940, partly due to the worst recruitment crisis since the implementation of the "all-volunteer" system. The reduction in the Army’s budget not only fails to meet and maintain its needs, but also does not meet the needs of the United States. National Defense Strategy requirements.

Finding 2: The Army has become the “leader” of the U.S. Department of Defense in developing new technologies and concepts, but the modernization of the service faces greater risks due to its low priority in the defense budget.

The ultra-large-scale combat requirements detailed in this article in the historical and contemporary data analysis have a significant impact on the U.S. Army’s force, combat readiness, and modernization. Nearly 80% of the service’s budget is consumed by basically fixed combat operations and sustainment costs, which greatly reduces the flexibility to fund its modernization, and continuous inflation in recent years has further exacerbated this situation. In contrast, the U.S. Navy and Air Force spend an average of less than 60% of their budgets on combat operations and sustainment, allowing the two services to fund their respective Invest more money in necessary modernization projects.

However, the recent U.S. defense budget has failed to fully balance the modernization funding gap between the various services. Since the implementation of the 2018 version of the National Defense Strategy, the Army’s annual modernization funding has decreased by $4 billion during the 2019-2023 fiscal years, while the Navy’s annual funding has increased by $10 billion and the Air Force has increased by nearly $20 billion. It is well known that in order to build a joint force with full-domain combat capabilities, only by making sufficient investments in Army modernization can the benefits of Navy and Air Force modernization investments be maximized, and vice versa.

Despite these challenges, But the U.S. Army has begun to demonstrate the combat capabilities it can provide to the joint force if it is well funded. Over the years, the service has begun to self-fund its modernization projects by cutting development funds for lower priority projects. For example, since 2022, the U.S. Army has begun testing directed energy weapons, will equip the United States’ first hypersonic weapons company in 2023, and strive to lead the world in improving vertical take-off and landing, tanks and armored vehicles, artillery and light weapons capabilities. However, this self-funded approach has its limitations and requires sufficient investment.

Finding 3: Preliminary observations on the Russian-Ukrainian conflict support historical data that the next war, even if it occurs in the Taiwan Strait, may be a full-domain conflict, and ground forces will play their traditional core role.

Russia’s attack on Ukraine in February 2022, the largest conventional war in Europe since World War II, provides real data and experience for this "debate" on defense strategy and defense budget priorities. Now a year into this rapidly evolving conflict, it is too early to draw conclusions, but several observations support the validity of the conclusions drawn in this article.

First, the outbreak of such a conflict in the heart of Europe demonstrates that it is difficult to accurately predict where the United States will fight next. As a global power, the United States cannot accept a situation where it takes too much risk in other important parts of the world, even as it struggles to meet the challenge of China’s increasing pressure.

Second, many of the key drivers that powered Ukrainian operations in the first nine months of the Russia-Ukraine conflict, such as long-range firepower, U.S. security force assistance, resilient communications, logistics support/support, and air and missile defense systems, are all top priorities of the U.S. Army’s modernization strategy.

Third, the Russia-Ukraine conflict clearly illustrates the importance of ground forces and shows that the current assumption that the U.S. Army will play a minimal role in Taiwan in the event of a conflict with mainland China is inaccurate. Ukraine’s situation reminds us that, first, it is difficult to achieve the political goal of controlling foreign territory without using ground forces, and second, the current forecast guiding the US defense budget that the next war will be primarily a “missile-centric” operation has been made before and has proven to be wrong.

In addition, despite the deterrent effect of Russian nuclear weapons on US policy in Ukraine, the current mainstream view is that the United States may attack Chinese military targets with nuclear weapons, or even on its own soil, when or even before the PLA begins to “liberate” Taiwan. However, a delayed US response may allow China to “liberate” Taiwan, so the Army may be sent in to restore Taiwan’s sovereignty along with the ground forces

Although it is well known that land warfare has been and will continue to be the “main event” in conflicts, the US Army’s modernization funding lags far behind other services. As Congress passes the 2023 defense budget and begins preparations for the 2024 budget authorization and appropriation cycle, based on the above "three key findings", we offer "three key recommendations’

Recommendation 1. Congress should prioritize Army modernization funding. In order to faithfully implement its National Defense Strategy and prepare for the next war, the United States must invest in the Army and its modernization in all aspects. If the investment model of the defense budget in recent years continues, the possibility of the next war in the United States will increase and more Americans will die. Based on this, the U.S. Army needs to significantly increase investment from 2024 to 2030 to achieve its modernization goals and maintain its advantage over near-peer opponents.

Recommendation 2. As the draft resumes, Congress should Ensure that the Army is restored to sustainable strength. It is unsustainable to cut Army funding to levels not seen since before World War II without reducing demand. Congress should not repeat the historical pattern of reducing the Army’s ultimate strength as the draft resumes; instead, it should develop a plan that clearly states how the Department of Defense intends to restore the Army to the level required to implement the National Defense Strategy; and it should direct the Department of Defense to develop a force structure sizing analysis framework so that it has an assessment mechanism for weighing forces.

Recommendation Three: Congress and the Department of Defense should ensure that Army and joint force funding and operations fully account for the service’s relevance in future contingencies. Ukraine’s history and current observations suggest that ground forces will play a major role in the next war. . The U.S. Congress and the Department of Defense now have many options to use the Army to strengthen deterrence. For example, they can explore opportunities to station troops in Taiwan, promote more contacts and cooperation between the Taiwan military, the Indo-Pacific Army Security Force Assistance Brigade, and the Army National Guard, and reserve key logistics support/guarantee capabilities in Taiwan. In addition, the U.S. Congress should also provide guidance and assessments on "If the defense budget forecast is wrong, what will the situation of the Taiwan Strait conflict be, what actions can be taken now to mitigate these consequences, and what size of troops are needed."

The U.S. Congress and the Department of Defense must keep in mind that Taiwan is only a potential emergency in a region. Therefore, Congress should assess and guide China’s actions to "liberate" Taiwan beyond the scope of Taiwan-including North Korea, Europe and the Middle East, as well as the Defense Department. How the budget supports preparedness for these other threats. Building a force that is too specialized for a single threat will leave the United States ill-prepared to defeat adversaries anywhere in the world. It goes without saying that the United States must build an Army that can win while protecting its soldiers for the next war.

The next war will likely be an all-domain conflict

The United States has never had a "good track record" of predicting the future, especially when it comes to complex national security issues such as war and peace. Wrong predictions have serious consequences, ultimately making war more likely and more destructive, and the consequences will be catastrophic; in the vast majority of cases, American soldiers and Marines in the field will pay a disproportionate price for wrong predictions.

One of the predictions we have made over and over again over the past century is that by shrinking the size of the ground force and cutting Army modernization funding, spending money on new technologies in the Department of Defense and other services, we will prevent the next war and make ground combat operations less likely. So far, this prediction has been wrong every time. Unfortunately, we are repeating the same mistakes. If we do not change course now, it is likely that the next war will come faster and be bloodier. Against this backdrop, it is necessary to analyze and evaluate historical and contemporary data on the needs of the U.S. Army, including the number of personnel and organizational units, the support and support capabilities of the forces for deterrence and combat operations, daily military operations and combat readiness; and the new technologies and weapons and equipment that need to be provided to the troops; considering some early observations in the Russian-Ukrainian conflict, the U.S. Army urgently needs adequate funding as the Department of Defense plans for future conflicts.

After 20 years of fighting terrorism and counterinsurgency, the 2018 National Defense Strategy sets a new course for U.S. national security policy. While we focus on fighting terrorism, China and Russia are also studying how to emulate our capabilities and methods to guide their forces to accelerate modernization investments and construction. Recognizing these worrying trends, the 2018 National Defense Strategy calls for a renewed focus on the dynamics of near-peer great adversaries. Moreover, terrorists and regional countries such as North Korea and Iran remain threats that we must be prepared to deal with. However, for the first time since the end of the Cold War, we must seriously consider fighting against technologically advanced and powerful adversaries. This has important implications for the U.S. military and its modernization. After operating in a "permissive and selective" environment for the past 20 years, U.S. forces have largely dealt with asymmetric small-scale threats and must now relearn to study large-scale combat operations. In the Pacific theater, increasing speed and range has become critical, and we need to accelerate investment in areas such as hypersonic weapons and future vertical takeoff and landing vehicles. The growing need for anti-access/area denial (A2/AD) defense capabilities is driving the development of new concepts such as "distributed operations" and "confrontational logistics" (meaning "logistics support/guarantee in a contested environment"), as well as increasing investment in improving survivability and developing advanced stealth technologies. Today, the United States is catching up and accelerating the modernization of its military to maintain its advantage over near-peer adversaries.

In fact, the U.S. National Defense Strategy has received broad bipartisan support in Congress. Recently, the basic principles of the 2018 National Defense Strategy (issued during the Republican administration) were approved in the 2022 National Defense Strategy issued during the Democratic administration; the core principle of viewing China as a looming challenge - China is the only country that may pose a sustained challenge to the U.S. military advantage, while Russia only poses a "serious threat" - has been retained. However, the 2022 National Defense Strategy does not detail what the change in direction means for specific modernization priorities, force investments, and posture requirements (i.e., force requirements for the five major theater commands of Indo-Pacific, Europe, Central, South, and Africa, and unknown for Northern Command). This is where different views and disagreements arise.

The mainstream view in Washington now is that the vast improvement in the United States’ defense capabilities in space, cyber, and anti-access/area denial are reducing the possibility of large-scale, all-domain operations. Based on this, "kinetic warfare" is transforming into "missile-centric" combat operations, mainly carried out in the sea and air domains; there is little demand for U.S. Army ground forces other than land-based long-range firepower, force protection, and logistical support

This view is not new. Over the last century, many U.S. defense policymakers and strategists made an almost unanimous prediction after every war that technological advances are fundamentally changing the nature of warfare, making all-domain operations less likely. In this view, investing enough in new technology will enable us to win the next war without going through the pain of ground combat, and offers a simple budgetary strategy: cut the size of the Army to fund investments by the Department of Defense and other services to develop new technologies. To varying degrees, this has been the policy that has followed the end of every war in the last century.

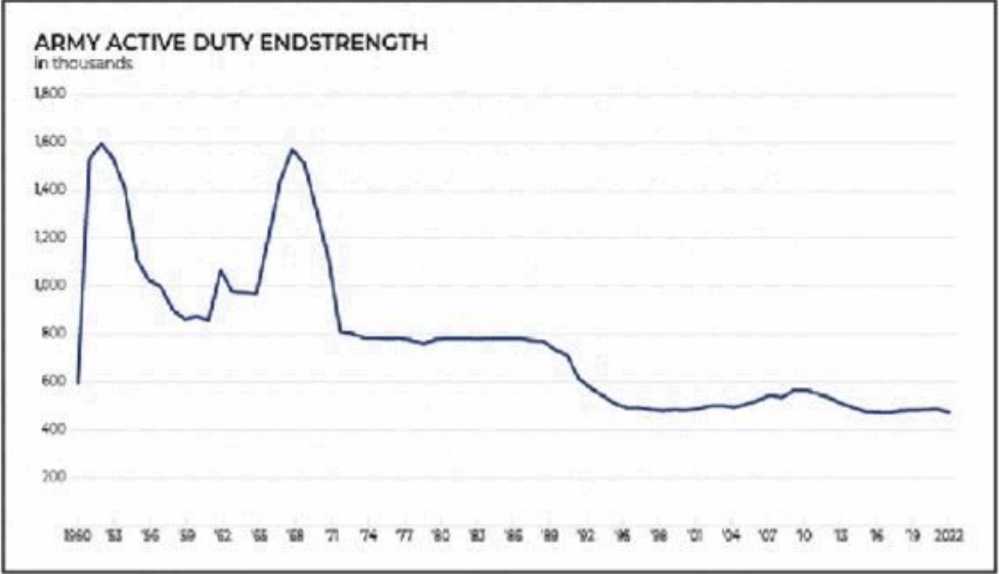

The end of World War II and the advent of nuclear weapons is one of the best examples. Statements published in American newspapers and journals in the late 1940s included: "The age of the infantry is gone. The service has gone extinct like the dodo. Yet this rather elementary fact seems to have escaped the attention of traditionalists in hiding who still stubbornly cling to their preference for the ’swarming’ infantry." "The age of the ground service is ending. Warfare has changed. The scientists have taken over strategy, and the military will sooner or later understand this. The era of fighting wars with these services is gone." American defense policymakers acted accordingly. While all military forces (i.e., the various services) faced major cuts after the war, the Army’s ground force personnel numbers fell by more than 90% between 1945 and 1950 (from about 6 million to just under 600,000). Modernization investments were even more skewed toward the other services: from 1948 to 1950, the Army received only about $1.4 billion, the Navy received $4.7 billion (2.4 times the Army), and the Air Force received $6.5 billion (3.7 times the Army).

While the advent of the atomic age and the advent of the Cold War justified the heavy investments in the U.S. Air Force and Navy, we now know that the drastic reductions in the size of the Army and the serious underinvestment in its ground force modernization programs were not based on an accurate assessment of the future, which led to extremely serious consequences. At the start of the Korean War, the Army received only 30% of the defense budget, but accounted for 40% of the total active U.S. military strength; during the war, the service provided 50% of the combat forces, deployed 64% of the troops, and suffered 82% of the total U.S. military deaths. The outcome of the Korean War might have been different (that is, American lives might have been saved) if the United States had focused on modernization, combat capability, and readiness of its ground forces as it did in the peacetime before the Korean War.

The recurring view that the next war will not be an all-domain conflict, despite the lessons of history, has had a "good market," and has been wrong every time. It is particularly ironic that the United States’ current focus on the Pacific theater is being used to some extent to prove this prediction wrong again - the United States has fought three wars in the Pacific in the past 100 years, all of which were large-scale land wars.

Some of the views do offer some credible predictions: there will be a war in the future, and it will likely be an all-domain conflict, with the U.S. Army providing the majority of the troops and suffering the greatest casualties. History shows that failure to prioritize ground combat readiness does not reduce the likelihood of conducting ground combat operations; rather, it increases the likelihood

Funding Trends in the U.S. National Defense Strategy

The 2018 National Defense Strategy suggests that defense spending needs to grow by 3% to 5% in real terms to fully implement the U.S. National Defense Strategy. The reality is that the actual spending capacity of the Department of Defense’s top budget has declined from 2019 to 2023, and the budget request for fiscal year 2023 is more than $200 billion lower than what is needed to achieve a 5% actual increase.

However, this decline in spending capacity does not include the Department of Defense itself and other military services. From fiscal years 2019 to 2023, the U.S. Army lost nearly $40 billion in purchasing power, while the Department of Defense and other military services basically achieved balance or slight growth. The budget funding growth is mainly in the fields of nuclear modernization and space, which are necessary investments for the United States to implement the National Defense Strategy. The challenge is that investments are needed in virtually all areas to maintain an advantage over near-peer competitors, deter their aggression, and win the war if deterrence fails. As noted above, a budgetary strategy that assumes the risk of ground combat does not make ground combat less likely.

To examine more specifically the mismatch between the NDS funding trends and the need to build a joint force capable of all-domain operations, this article will focus on force and modernization. To understand these investment areas, the Department of Defense budget can be broken down into core funding categories: President Biden’s fiscal 2023 defense budget request includes $177 billion for the Department of the Army; in contrast, the Department of the Navy receives $231 billion, the Department of the Air Force $234 billion, and the Department of Defense and the services share $131 billion. The total budget submitted by the Department of Defense is $773 billion.

However, such a comparison can be misleading because the Department of the Navy includes the Navy and the Marine Corps, the Department of the Air Force includes the Air Force and the Space Force, and $40 billion of the Air Force budget is used for other national security needs. Adjusting for these differences, the Navy requested $181 billion and the Air Force $170 billion. In other words, the top budgets for the three services are roughly equal.

Each service’s budget can be divided into major appropriation items, including military personnel, operation and maintenance/maintenance, research and development/test and evaluation, procurement, military construction, and some miscellaneous items. Among them, the largest appropriation items will be divided into two categories: one is combat operations and continuous support projects, including military personnel and operation and maintenance, which refers to the personnel, combat operations, combat readiness and equipment support operating costs of each service department; the second is modernization projects, including research and development, test and evaluation, and procurement, etc., which are intended to provide a measure for future investment in new and replacement equipment. The remaining appropriation items average about $4 billion, accounting for 2% of each service department’s budget, and this article does not discuss these issues further.

Army Forces: The Heart of DoD’s Combat and Peace Operations

As the Secretary of the Army noted at an Atlantic Council event, “We are operating around the world every day.” It is widely acknowledged that the Army provides the most troops and incurs the most casualties when war breaks out, but it is less recognized that this is also true in peacetime.

Over the past two years, the Army, with less than 50% of the active-duty strength of all services, provided 75% of U.S. joint force support operations in Ukraine; 80% of its National Guard COVID-19 response operations; 80% of border security support operations; and completed two-thirds of the readiness missions requested by the Joint Staff, as well as providing more than half of the global requirements of combatant commands. However, the Army has no control over these requirements, which are external demands imposed on the service. These huge external demands have a significant impact on the Army’s force size, readiness, budget funding, and modernization.

President Biden’s 2023 defense budget includes funding for 473,000 U.S. Army soldiers to eventually serve on active duty. This means that the service will have 12,000 fewer troops on active duty this year than in 2022, the smallest final active duty force for the Army since 1940.

With a 12,000-troop reduction, the Army will have the smallest active-duty force since 1940.

Demands for Army units

This final decline in active duty strength occurs when the demands on the U.S. Army are large and growing. To illustrate the role of the service and the burden it bears relative to its force size, the chart shows the various demands on the U.S. Army units and their proportion of those demands (the chart also includes data for the Navy, Air Force/Space Force, and Marine Corps), as well as data for several major combat operations, daily operations, and situational requirements. The first part of the chart shows the final active force corresponding to the amount of money allocated to the Army in President Biden’s 2023 defense budget (i.e., 473,000). As mentioned above, this size of final active force is the smallest since 1940, accounting for about 36% of the final active force of all services; if the National Guard and Reserve forces are included, the final active force is 998,500, accounting for about 47% of the final active force of all services.

In addition, the chart also shows several major wars that the United States has recently participated in. A striking pattern over the past 100 years is that in every major war, the Army has an average of about 50% of its troops participating in the war, with a deployment ratio of as much as 2/3, and about 70% to 80% of the deaths. The largest deviation was in the Pacific Theater during World War II, when the number of deaths among the services was more evenly distributed. Even so, one might still think that the US Navy and Air Force suffered the heaviest blows. In fact, the Army also suffered a disproportionately large number of deaths. Empirical predictions of the needs of the next war will be based on these relevant data.

These statistics prompted Secretary of Defense Mattis to establish the Close Combat Lethality Task Force in 2018. In his memo announcing the formation, he stated: “The creation of this task force is driven by my commitment to improving the readiness, lethality, survivability, and resiliency of our historical close combat ground formations, which historically have suffered approximately 90 percent of casualties, yet our personnel policies, training methodologies, and equipment have not kept pace with changes in available technology, human factors science, and talent management best practices.”

As discussed above, despite Secretary Mattis’s attempts to increase the focus on the U.S. Army’s ground forces, Washington is pushing budget priorities with the view that this pattern will not repeat itself in the next war.

There is a belief that combat operations are shifting to the sea and air domains, and we can take risks with ground combat forces. This contradicts the Department of Defense’s own combat plans.

The Joint Staff’s Directed Readiness Table provides guidance to the U.S. military services on the number of troops that must be deployed with a high level of readiness when the current combat plan is initiated. These data are confidential, but the Army’s force ratio has been made public, accounting for about 66% of these combat readiness requirements. Data related to the temporary deployment of troops by the U.S. Army to support several recent crises. As mentioned above, the U.S. Army has provided approximately 70% to 90% of the troops for several major deployment operations in the past few years.

The deployed forces of the U.S. Army are also evident in the Global Force Management Allocation Plan data. The plan is a basic standard provided by the Department of Defense for force deployments for the next year, which is designed to track deployments throughout the year (as crises and other factors adjust the plan). While GFM data is classified and the Army has less than half of the total strength of all the services, the service is required to deploy about 56% of its forces under the plan. This number changes throughout the year, but is not expected to be lower than this proportion.

Finally, the U.S. military’s force requirements for long-term deployments under the GFM plan. Not surprisingly, the European and Indo-Pacific theater commands have the largest force requirements. Perhaps surprisingly to some, the Army has deployed the most troops in the Indo-Pacific theater command area of responsibility (including troops stationed in Alaska and Hawaii). The service’s forces deployed to these two theater commands are roughly proportional to its final active force strength.

Other overseas theater commands have relatively small forces deployed in their areas of responsibility because they rely more on temporary deployments. Currently, the U.S. military presence in the Middle East is mainly composed of Army soldiers; South America and Africa are also areas where the service has deployed a large number of troops, such as 1,000 Army National Guardsmen deployed in the Horn of Africa.

The role of the Army

The role of the U.S. Army can be divided into carrying out combat missions, meeting daily needs, and supporting general services (including combat and non-combat services). Once war breaks out, the service’s leading, central, and coordinating role in combat operations will become prominent. However, in peacetime, the focus turns to (supporting) new war theories, and the lessons of past wars fade away. In response to this phenomenon, the focus of our recent and current debates is the potential Taiwan Strait issue. As one expert recently said: "It is very likely that U.S. decision-makers will require the Army to play a role in this conflict other than what has been presented so far, namely launching missiles or providing "advice" to Taiwan’s senior military departments; instead, the U.S. Army may find itself either defending Taiwan from China’s "liberation" or helping to retake Taiwan after China (due to close proximity and first-mover advantage) wins the initial high-tech game."

In short, if the Army cannot play its traditional leading role, the United States is unlikely to participate in large-scale combat operations in the near future. If the service lacks the troops and modern equipment it needs, the United States will be at a distinct disadvantage, as it did in the Korean War.

If anything, the operational demands on the Army are increasing. As the Marine Corps’ ground combat capabilities in the tank and armored vehicle field decline, the Army will be asked to compensate. Future operations in urban areas and contested environments, as well as the need for tank and armored forces to protect both the European and Pacific theaters, now fall squarely on the Army.

In peacetime, the day-to-day role of military forces focuses on deterring adversaries (i.e., trying to prevent or delay the next war) and preparing for war. Not surprisingly, the Army plays a major role in these demands. Experience shows that the service’s military presence and the size of its deployed forces are the most powerful conventional deterrent. Looking at past conflicts and those in conflict, RAND researchers found that heavy ground forces provided the most deterrent effect, while air and naval forces provided little deterrent effect; they also found that heavy ground forces and air defense forces/weapons provided the same deterrent effect when deployed in general combat areas of concern (but not necessarily on the front lines of a potential conflict).

In 2022, Admiral Aquilino, the current commander of the U.S. Indo-Pacific Command, said: "The U.S. military has an operational advantage in our operational design. Forces located west of the International Date Line can provide in-depth defense, enabling the joint force to respond decisively to emergencies in the region. Relatively dispersed combat forces can both improve survivability and reduce risks, and can quickly switch from defense to offense when deterrence fails. A forward and rotationally deployed joint force with appropriate combat power is the most reliable way to demonstrate determination, ensure the security of allies and partners, and provide the President of the United States and the Secretary of State with a variety of options."

The U.S. Army can provide the President and the Secretary of Defense with operational flexibility, especially when taking joint actions with the Navy and the Air Force, which can be adjusted for specific situations, thereby more or less improving combat effectiveness. To some extent, cutting the final active strength of the Army by 12,000 has limited the options of senior leaders.

In addition, the military leaders of many countries in the Pacific theater grew up from the army forces of their respective countries, and the U.S. Army is best able to establish lasting relationships with these allies and partners. These military leaders tend to regard the Army as the most reliable and lasting partner (a partner that can bring resources and keep its promises). Establishing a strong and credible deterrence in this theater requires a modernized U.S. Army with a good combat readiness to maintain and develop these relationships and work with these countries to enhance the capabilities needed to maintain regional stability.

Another factor that increases its demand is that the U.S. Army has always been the main executor of universal services on the battlefield, which is related to its leading role in coordinating combat operations.

The universal services that the U.S. Army needs to perform mainly include: land-based air and missile defense; fire support; base defense; transportation; fuel distribution; general engineering construction; intra-theater medical evacuation; logistics management; communications support; chemical, biological, radiological and nuclear defense, and explosive ordnance disposal. Other universal services are mainly concentrated in defense agencies responsible for reporting to the Office of the Secretary of Defense and in field activities. For example, the Defense Logistics Agency, the Chemical and Biological Defense Program, and the Defense Health Program. But even these common services are often supported primarily by the Army behind the scenes (such as the research and acquisition activities of the Chemical and Biological Defense Program for vaccines, protective equipment, and other defense measures). The Chemical and Biological Defense Program is at the heart of Operation Warp Speed and the development of the COVID-19 vaccine; although it needs to report to the Under Secretary of Defense for Acquisition and Support and has a dedicated person to supervise it, most of the program’s projects are executed by the Army.

All of these requirements constitute the fixed consumption costs of the U.S. Army. Regardless of its final active force strength, the service still needs to perform these common services. Therefore, when its final active force strength is reduced, the U.S. Army will have to cut from its direct combat personnel.

(To be continued)