Of course, unlike the Soviets who tried to put all the most powerful firepower on the T-27 chassis, the British who were reorganizing their military were pragmatic in applying the military value of the "Carden Lloyd" MKVI. The main idea was to use it as a mobile vehicle for a standard machine gun squad of the British Army. As for the strong internal logic behind such behavior - the British Army has always had a tradition of attaching importance to machine guns. During the heyday of the British Empire, it was precisely by virtue of the keen perception of the tactical value of machine guns that the reputation of the British Army and even the entire United Kingdom reached an unprecedented height. Take the British Army’s use of machine guns when suppressing the Mahdi Rebellion in Sudan as an example. Since the 1870s, the British Empire has begun to expand its influence to Sudan in Africa. Before the British went to Sudan, this war-torn country had always belonged to the sphere of influence of the Ottoman Empire and Egypt. In 1873, Gordon led the British army to Sudan and was appointed as the local governor. Shortly after Gordon went to Sudan, a Sudanese named Ahmed launched an uprising against the British colonists. The Sudanese claimed to be Mahdi (savior) and spread propaganda to drive the British out of Sudan. Therefore, Arabs in southern Egypt and Sudan followed him, which was known as the Mahdi Rebellion. After Mahdi launched the uprising, tens of thousands of Arab cavalry gathered around him. With their superb riding skills and sharp Damascus knives, they successfully defeated the British army led by Gordon. On January 26, 1885, Gordon died in battle after being besieged for several months. Mahdi’s army successfully captured Khartoum, the largest city in Sudan, and then announced the establishment of the Mahdi Kingdom. Shortly after Khartoum was captured, Mahdi died of illness. Before his death, he passed the throne to his subordinate Abdullah. After Abdullah ascended the throne, he defeated the separatist forces in the country and became the only monarch in Sudan. He also established a parliament in imitation of Western countries, and in order to promote economic prosperity, he ordered the issuance of the first set of currency in Sudan’s history. In 1898, nearly ten years after Gordon’s death, the Mahdi Kingdom had gradually begun to stabilize. At this time, more than 8,000 British soldiers equipped with new weapons set out from Egypt to expedition to the Mahdi Kingdom. Abdullah immediately went to fight, but he was defeated in every battle, so he led his army to prepare to defend Khartoum.

After Abdullah hid in Khartoum, a small group of British soldiers went to Khartoum to shout. Seeing that the number of British soldiers was small, Abdullah led 50,000 Arab cavalry to chase those British soldiers, and chased them all the way to an open space in Sturman, north of Khartoum, where more than 8,000 British soldiers had been waiting for a long time. Just as tens of thousands of Arab cavalry rushed to the British defense line, the British brought out 20 Maxim heavy machine guns. In just a few minutes, Abdullah’s cavalry fell one after another like autumn wind sweeping fallen leaves, and the bodies of people and horses piled up into hills. The army of the Mahdi Kingdom was hit by the dense firepower network of the British army and suffered heavy casualties, but Abdullah was still unwilling to retreat and ordered the cavalry to charge the British defense line. As a result, the charge again and again was a fearless sacrifice, and no cavalry could enter the British defense line alive. This battle with a huge disparity in strength ended with the complete retreat of the Mahdi army. About 20,000 Arab cavalry were killed, more than 5,000 were captured, and only 47 British soldiers were killed. After the battle, the British army successfully captured Khartoum, and the British Empire entered its most prosperous era.

The First World War more than a decade later was the golden age of machine guns. Heavy machine guns equipped with heavy gun mounts and continuous firing capabilities played a huge role in defensive operations, and the form of war changed accordingly. After World War I, there would no longer be officers waving batons and standing in the front, leading the entire team to walk slowly towards the enemy’s position in a dense formation. The spear cavalry that had traversed the Eurasian continent for thousands of years lost its value in just a few years. Traditional nomadic peoples had no other way to go except singing and dancing. In World War I, although the British Army was also confined to the mud of trench warfare, machine guns were the most important tool for it to win this bloody war in the end. After Vickers acquired Maxim in 1896, Albert Vickers improved Maxim’s design and launched the Vickers machine gun. The gun was officially adopted by the British Army in 1912 and was the standard heavy machine gun of the British Army for 56 years. Compared with Maxim’s original design, the Vickers machine gun reduced the size and weight of the receiver, strengthened the components with alloy materials, and installed a muzzle stop. The theoretical rate of fire of the gun is 450 to 500 rounds per minute, the water jacket is filled with 3.5 liters of water, and it enters a boiling state after 3 minutes of shooting, so a steam condensation barrel connected by a hose is configured. The Vickers machine gun is the most reliable of its kind and can be called a deadly weapon. In August 1916, the 100th Machine Gun Company fired continuously for 12 hours with 10 Vickers, and each gun fired an average of 100,000 rounds of bullets. It is worth noting that although the main machine gun equipped by the British Army in World War I was the Vickers water-cooled heavy machine gun improved from the Maxim design, light machine guns such as Madsen and Lewis also gained a certain degree of popularity in the British Army. Among them, the Madsen 1902 light machine gun is considered to be the earliest light machine gun in the world. Before World War I, the armies of Austria-Hungary, Tsarist Russia, France, Britain, Sweden and other countries were equipped with a lot of Madsen light machine guns. As for the Lewis light machine gun, its designer graduated from the United States Military Academy at West Point. The gun adopts the gas-operated automatic principle and the bolt rotary locking method. The bolt tail locking catch makes a semicircular movement to open and close the lock. It is equipped with a rate of fire adjustment device, with a rate of fire of 550~750 rounds per minute. However, this new light machine gun not only did not receive the attention of the US Army, but was considered by some stubborn "good leaders to be opportunistic". Therefore, Lewis deeply realized the strength of the opposition and decided to find another way out for his light machine gun. After several twists and turns, the Lewis machine gun came to Europe and became a light machine gun widely equipped by the Commonwealth Army in World War I. It was not only put on airplanes to become an aviation machine gun, but also became a sharp weapon in trench warfare with its mobility and flexibility.

After the end of World War I, most of the major British military theorists, as low-level officers at the time, personally experienced the inefficiency and waste of fighting in World War I. They were convinced that there would be a new war soon and had almost no confidence in international treaties or the League of Nations. They were obsessed with learning the "correct lessons" of World War I, reviewing the framework structure of the army, and restoring the mobility of combat. Therefore, they were more interested in light machine guns with good portability rather than heavy machine guns, and tried their best to ask the military to use light machine guns as the basic firepower of infantry units. It was also under this call that the Czech-made ZB-26 light machine gun entered the British Army’s field of vision in the early 1930s.

At the end of World War I, Czechoslovakia rose from the ruins of the Austro-Hungarian Empire. The new country soon found itself surrounded by other new countries, some of which had conflicting territorial claims, and the Czechs began to form a new army. With limited resources and the factory on the verge of bankruptcy, the three brothers, local weapons manufacturers, produced a light machine gun that could be used with infantry mobile operations. The ZB26 was adopted by the Czech Army and widely exported. More were sold to foreign buyers than to the Czech Army, and one important sub-model was the British Bren machine gun. At the time, the British Army was mainly equipped with two types of machine guns for very different tactical tasks. The battalion level used the Vickers machine gun, a relatively heavy weapon that was extremely reliable and could produce a strong fire curtain as long as there was ammunition and cooling water. But it was a complex weapon that required specially trained personnel, and the weight of the gun and its need for water and ammunition meant that it was essentially limited to static defense. The Lewis light machine gun for platoon level was designed to be light enough to provide fire support for advancing infantry, but still relatively complex and cumbersome. In the 1930s, the British began to seriously study a new weapon to replace the complex and cumbersome Lewis machine gun. They originally favored the Browning automatic rifle, which was lighter and more reliable than the Lewis machine gun, but this plan was never implemented because Britain was unwilling to spend money on weapons in peacetime. In 1930, the British Small Arms Committee decided to hold a large-scale bidding competition for the standard light machine gun used by the British Army in the future. The participating manufacturers came from many well-known arms companies in the UK and abroad. Among them, the Czech ZB-27 light machine gun was outstanding for its "exquisite design, excellent workmanship and exquisite materials", and won the favor of the British Small Arms Committee. According to the British request, the chief designer of the ZB-26 light machine gun, Favaclav Holik, went to the Royal Small Arms Factory in Enfield, England, to remove the heat sink on the barrel of the ZB-27 light machine gun, and moved the dial-type sight directly below the magazine to the side and rear of the magazine, and finally modified it to ZGB-34. The machine gun uses 7.7 mm British bullets, is 1.15 meters long, weighs 10.5 kg, has a firing rate of 500 rounds per minute, and is fed by a 30-round curved magazine. It can choose single-shot and continuous shooting, and can quickly replace the barrel. The performance of the machine gun during the test was amazing. After firing 146,802 rounds of bullets continuously, the UK decided to end the test and immediately purchased the production license of the ZGB-34 light machine gun from the Czech Republic, naming it the Bren machine gun. Its name comes from the Czechoslovak manufacturer Brno and the British manufacturer Enfield, and is composed of the letters Br from Brno and Enfeld from Enfeld.

The Bren machine gun adopts the gas-operated working principle and the bolt deflection locking method, that is, the rear end of the bolt is lifted up and locked into the locking groove of the receiver to achieve locking. The barrel caliber of the Bren light machine gun was changed to British 0.303 inches (7.7 mm), and it fired the standard rifle bullet of the British army. The 30-round magazine was located above the receiver and the shells were ejected from the bottom. In order to adapt to the rimmed rifle bullets used by the British army, it was changed to an arc-shaped magazine. Since the magazine was directly above the receiver, the front sight with wings and the peep sight of the gun were installed on the left side of the gun body, and a trumpet-shaped flash suppressor was installed at the barrel. The gun shortened the barrel and gas pipe, and eliminated the barrel heat sink, which is a clear difference from the ZB-26 light machine gun. There is a gas regulator at the front end of the gas pipe with 4 gears, each gear corresponds to a vent of different diameters, which can adjust the amount of gunpowder gas entering the gas guide device when the bullet is fired. When shooting, the bolt handle does not move forward and backward with the bolt. The bolt handle can be folded and folded back when marching to avoid being pulled while marching. Dust covers are installed on the openings of the receiver such as the feed port, ejection port, and bolt handle. The Bren light machine gun uses a handle and a barrel fixing bolt to quickly change the barrel. The gun uses a bipod and can also be mounted on a tripod to improve shooting stability.

The Bren machine gun is a carefully crafted weapon. The Czech machine gun is known for its fine manufacturing process. The Bren series of light machine guns developed from the Czech light machine gun naturally inherited this advantage. The Bren machine gun is also manufactured to a high standard with excellent accuracy and reliability. There are a total of 3284 assembly steps for each machine gun, which inevitably means high production costs. Each gun was initially sold for £40, but later it dropped significantly. The British Army attaches great importance to the role of the Bren machine gun as the firepower backbone of the infantry unit, and regards it as the main killing force of the entire infantry unit. Every infantry unit’s tactical action must be carried out around the Bren machine gun. In the 1930s, the British infantry squad was divided into a 7-man rifle group and a 3-man Bren group. Each rifleman had to carry a Bren magazine. In addition to the Bren light machine gun, the Bren group also brought 9 spare magazines, a machete, a mattock and spare barrels. Riflemen provide security for them and replace casualties when necessary. Becoming a Bren gunner requires a series of courses, covering tactical use, choosing the right position when shooting, and maintaining weapons. In the initial recruit training, all infantrymen learned the basics of using the Bren machine gun. Generally speaking, only the No. 1 shooter will learn some less common skills, such as mounting the weapon on a tripod, and only they will get the Bren gun expert badge worn on their sleeves. Although the Bren light machine gun has a capacity of 30 rounds, which affects the continuity of firepower, it is still a key factor in maintaining firepower for British infantry equipped with manual rifles. In the attack, the infantry squad can be divided into two parts and advance forward at a certain speed. The Bren group and the rifle group take turns to provide cover for the other group. One group must be in a state of firing at all times. Providing covering firepower is the primary task of the Bren machine gun in the attack, that is, to help the riflemen advance. In defense, the Bren machine guns are placed at the end of the fortifications so that they can fire along the attack line and allow more attackers to enter the attacked area. The main role is to provide continuous fire suppression, such as gun holes in enemy bunkers and cover small groups of scattered soldiers.

At the same time, as another measure to restore the mobility of the troops, many people in the British Army are also interested in the idea of improving the battlefield vitality of machine gun teams through mechanization and motorization. Interestingly, this inspiration was also supported in practice by the Canadian Army’s motorized machine gun brigade in World War I. The emergence of the Canadian Army Machine Gun Brigade was not actually proposed by the military, but by a group of wealthy Canadian businessmen about one month after the outbreak of World War I. They planned to pay for the formation of a unit with machine guns as the main equipment for the troops, and armored vehicles as mobile tools. The Canadian military readily agreed to the proposal of the wealthy businessmen. After all, someone paid for the equipment, and they only needed to recruit and train personnel, so why not? Moreover, the value of machine guns had been proven in the first month of the war, and Canada itself really needed to try new tactics.

On September 9, 1914, about half a month after the establishment of the Canadian Expeditionary Force, the First Canadian Motor Brigade was established. The first commander was Major General Raymond Brutier, an immigrant from France. He also had 9 officers and another 114 grassroots personnel of different levels. It was these people who formed the basis of the machine gun brigade. In the initial weapons and equipment configuration, the machine gun brigade had only 8 armored cars designed and manufactured by the Pennsylvania Automobile Company. This armored vehicle was like a van with welded steel plates, with an open top structure, a cab in front and a fighting compartment in the back. The main weapon was two machine guns arranged in front and behind the fighting compartment. They were originally American Colt M1914 machine guns, which were an improved version of the "potato digger" Colt M1895. This machine gun was not equipped too much, and was later replaced by the British Vickers machine gun. The infantry who assisted in the battle carried rifles like regular infantry. In addition, the machine gun brigade also had 6 unarmored cars for support, 4 ordinary cars, which might be used for material transportation and communication, and an ambulance. Because of the relationship between Canada and Britain at that time, the First Machine Gun Brigade of Canada soon went to Britain as part of the Commonwealth Army to prepare for combat. However, the arrival of the brigade made the British worried. At that time, the concept of mechanization was still in its infancy, and the war was mainly based on infantry, artillery and cavalry. Tanks had not yet appeared. The commander did not know what combat unit such a highly mechanized force should belong to, nor did he know what combat missions they should perform. In the end, the brigade was treated as a cavalry unit to perform tasks. They cooperated with almost all the troops around them. With their high-speed mobility, they were widely involved in offensive operations, retreats, defenses and other battles. Using the mobility of cars, it is possible to quickly organize machine gun positions in a certain place with the help of the rich transportation routes in Europe, which is especially important in the retreat when the overall situation is unfavorable. The First Machine Gun Brigade fought for 3 years, and their achievements were recognized by the army. So in early 1918, Canada decided to expand its scale and form the Second Machine Gun Brigade. The two brigades were each equipped with 40 machine guns, and were equipped with support and medical units. They also shared a 300-man bicycle infantry unit to cooperate in combat. This configuration was considered to be highly mechanized during World War I. No wonder some people called this unit the pioneer of mechanization in the Commonwealth Army.

The Second Machine Gun Brigade had combat capabilities in early 1918. It fought side by side with the First Brigade and played a vital role in blocking the spring counter-offensive launched by the German army. In addition, in the late 1920s, the British War Office and the General Staff began to worry more and more about the reduction in the number of British Army troops, the deterioration of equipment, and the inability to fulfill possible obligations. Compared with before 1914, the planned expeditionary force to fulfill obligations outside Europe was much smaller in scale and less prepared to go to the battlefield at any time. It was under these unfavorable conditions that the British Army conducted a series of remarkable mechanized mixed force experimental exercises between 1927 and 1931.

For example, the so-called mechanized forces that conducted the first round of formal exercises on Salisbury Plain in August 1927 were a hodgepodge of armored vehicles, light and medium tanks, cavalry, tractor-drawn artillery, and infantry transported by trucks and half-track vehicles. The brigade commander, Colonel Jack Collins, divided the brigade into three groups, "fast", "fast" and "slow", according to the road speed of their respective vehicles, which was not in line with their off-road capabilities. As Liddell Hart reported in the Daily Telegraph, the result was a long column that meandered for 52 kilometers, often huddled in bottlenecks. The lack of radio communications and effective anti-tank guns (replaced by colorful flags) were just two of many serious shortcomings. Even so, the exercise still proved the superiority of mechanized forces over traditional infantry and cavalry. In the 1928 exercises, the unit, renamed "Armored Corps", was equipped with 150 radio sets, but the applicable tanks and vehicles were still always There was a shortage of only 16 light tanks available, and these lacked turrets and were armed only with machine guns. Although excellent replacements for the old Vickers medium tanks were designed, their development was hampered by a lack of funds, and the use of motorised transport by infantry prevented them from keeping up with the tanks off-road. However, the most successful aspect of the 1928 exercise was the successful performance of the well-rehearsed roundabout manoeuvre. The pinnacle of the British Army’s mechanised experiments in the early 1930s was the exercises held by the 1st Royal Tank Brigade in 1931. Unlike all its predecessors, this unit was composed entirely of tracked vehicles. Another important feature was that each company within each tank battalion consisted of a part medium tank and a part light tank, demonstrating the effectiveness of both types of tanks. Tanks can work together. By combining radios and colored flags as a means of communicating between tanks, Brigadier General Charles Broad developed a method of drill that allowed the brigade of about 180 tanks to move as a whole under his command. Broad led the brigade through the fog for miles across Salisbury Plain, appeared on time for the observation site, and marched past the reviewing Army Council with "superb precision", and the exercise ended in a great success.

The three detachments of "Fast" and "Slow", however, did not match their off-road capabilities. As Liddell Hart reported in the Daily Telegraph, the result was a long column that meandered for 52 kilometers, often huddled in bottlenecks. The lack of radio communications and effective anti-tank guns (replaced by colorful flags) were just two of many serious shortcomings. Even so, the exercise still demonstrated the superiority of mechanized forces over traditional infantry and cavalry. For the 1928 exercises, the unit, renamed the "Armored Corps", was equipped with 150 radio sets, but suitable tanks and vehicles were still in short supply. Only 16 light tanks were available, and they lacked turrets and were equipped only with machine guns. Although excellent replacements for the old "Vickers" medium tanks were designed, lack of funds hampered their development, and the use of motorized transportation by infantry could not keep up with the tanks off-road. However, the most successful point of the 1928 exercises was the successful performance of the roundabout maneuvers that had been repeatedly practiced beforehand. The pinnacle of the British Army’s mechanization experiments in the early 1930s was the 1931 exercises of the 1st Royal Tank Brigade. Unlike all its predecessors, this unit was composed entirely of tracked vehicles. Another important feature was that each company within each tank battalion consisted of a portion of medium tanks and a portion of light tanks, demonstrating that the two types of tanks could operate together. By combining radios and colored flags as a means of communicating between tanks, Brigadier Charles Broad developed a drill that enabled the brigade of about 180 tanks to move back and forth as a unit under his command. Broad commanded the brigade to march several miles across Salisbury Plain in heavy fog, appear on time for the observation site, and march past the reviewing Army Council with "superb precision", so that the exercise ended in a great success.

At least as important as these early mechanized field exercises, the British military also published the first official guide to mechanized warfare in 1929, which was Broad’s The pamphlet, Mechanised Armoured Arrays, was widely known as the "Purple Primer" because of the colour of its cover. This manual had a major influence on the British doctrine of mechanised warfare in the 1930s and was also carefully studied in Germany. The core of Broad’s thinking was that tanks should be used primarily in the offensive to exert their firepower and assault power, and therefore ideally they should be used in independent arrays. Although Broad was understandably cautious, the picture he outlined - independent use of armoured forces to break through enemy lines, cut off their communications and disrupt their rear - was indeed a fantasy given the performance and organisation of tanks at the time. Unless all arms of the British Army were able to achieve armoured mechanisation, this would inevitably involve the issue of armoured mechanisation of the infantry. After this short period of ambitious experimentation, the push and inspiration from military leaders waned significantly, partly due to the increasing caution and conservatism of Sir George Milne, the Chief of the Imperial General Staff. By the time he finally retired in 1933, there were still only four fully-formed tank battalions, and only two of the 20 cavalry regiments had replaced horses with armored vehicles. As with traditional military conservatism, the fiscal crisis of 1931 severely restricted military spending, greatly hindering further innovation and experimentation. Even so, the British Army’s preference for light machine guns after World War I, the impressive Canadian Motor Machine Gun Brigade in World War I, and a series of mechanized unit experiments on Salisbury Plain, all these factors combined to have an impact when the opportunity for rearmament arrived in the mid-1930s, and the result was an attempt to combine the Bren machine gun team with the "Carden Lloyd" MK VI.

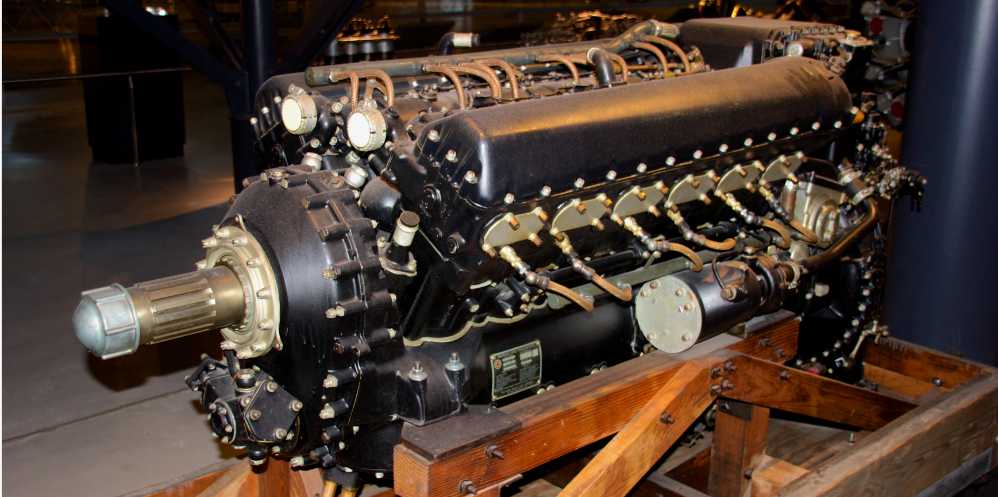

In 1935, Vickers Armstrong launched the initial prototype, the VA.D50 machine gun carrier. From the outside, this new product was not exciting. The VA.D50 inherited the narrow interior characteristics of the "Carden Lloyd" MKVI, with only enough space in the front for two people to sit. The engine and reverse gearbox were directly used from Ford, and were compactly placed in the middle and rear of the vehicle body respectively. The suspension system of the D50 was improved on the basis of the "Carden Lloyd" MKVI, using a balanced coil spring structure, which was excellent at that time, but what really made it outstanding was its steering system. Previously, the "Carden Lloyd" series of tankettes often had steering failures, and sometimes even accidents where the steering results were the opposite of the operation, but this problem was successfully solved by John Carden, the chief designer of Vickers. Through the principle of sliding steering, he changed the steering operation to be mainly completed by the steering wheel, rather than the frequent involvement of the vehicle clutch as before. It was precisely because of this that the D50 carrier performed very well in terms of turning radius and other performance, and finally won the recognition of the testers on the scene. The D50 not only passed the undulating roads smoothly, but also had a smaller turning radius than any other similar vehicle of the same period. The significance of this vehicle lies in determining the personnel configuration specifications for machine gun carriers. The D50 is nominally a multi-purpose vehicle, a so-called universal transport vehicle, But the main design focus is to carry a complete machine gun crew. There were two methods of personnel configuration at the time, the crew and the machine gun crew were independent of each other or the crew served as machine gunners. The advent of VA.D50 convinced the British Army that the latter configuration was more practical. D50 further increased the military’s enthusiasm for ultra-light general-purpose transport vehicles/machine gun carriers. The success of the VA.D50 machine gun carrier further increased the enthusiasm of the British military. They decided to equip VA.D50 on a small scale while asking Vickers to develop a better machine gun carrier. After being accepted by the military, Vickers first delivered the first batch of machine gun carriers to the British War Department. The vehicle is 3.6 meters long, 2.1 meters wide, and 1.6 meters high. It is a very pocket-sized model. If a standard-sized British armored soldier stands on it Next to it, the roof reaches just to the chest. The new model uses the engine, transmission and suspension system of the D50, with 3 road wheels on each side, the idler in front and the driving wheel in the back. The 1st and 2nd road wheels share a suspension, and the 3rd road wheel uses an independent suspension. The new model is equipped with a 62.5-kW Ford V8 water-cooled gasoline engine, mechanical transmission with a 4-speed gearbox, a fuel tank capacity of 90 liters, a maximum road speed of 48 km/h, and a maximum reserve range of 225 km. The car body is composed of 4 armor plates, the top is completely open, the armor is 4~10 mm thick, and the bottom armor is 3 mm thick. It is the weakest part of the car and it is difficult to resist attacks from mine fragments. The cockpit and the carrier compartment are separated by a partition, with the driver on the right and the machine gunner on the left. The vehicle weighs 3.75 tons and has a standard crew of 3~4 people, including One person is the driver, and 2~3 people are machine gunners. The standard armament is a Vickers 7.7mm water-cooled heavy machine gun, or a Boyce anti-tank gun. In December 1935, the military officially named the vehicle the MKI No. 1 machine gun carrier. However, the No. 1 vehicle was only a pre-production model. The designers quickly modified its machine gun position and developed the 4.5-ton MKI No. 2 vehicle, which was officially equipped to the troops in late 1937. The machine gunner’s cabin was changed from the original position flush with the front of the vehicle to protrude from the front of the vehicle, and the armor thickness was increased to 12 mm. Although this change greatly facilitated the machine gunner, it affected the driver’s left line of sight. In addition, the Vickers water-cooled heavy machine gun carried was not only large in size, but also too heavy and difficult to remove from the vehicle quickly, which greatly affected the evaluation of the use of this vehicle. Although the British Army also tried to replace these improved MKI machine gun carriers with other weapons, such as mortars and 2-pound anti-tank guns, the results were very unsatisfactory. However, all these troubles tended to dissipate as the mass production of the Bren machine gun was put on the agenda. In September 1937, the first British-made Bren Mk1 light machine gun rolled off the production line at the Enfield factory. Mass production officially began in 1938, and the production rate increased to 300 per week. In 1938, the John Inglis factory in Toronto, Canada also began to produce Bren machine guns. The MKI machine gun carrier carries a Vickers 7.7mm water-cooled heavy machine gun, and it takes three people to carry its body, tripod and ammunition box. In comparison, the Bren light machine gun that can be carried by a single soldier is much lighter and more flexible, and it also meets the design intention of the machine gun carrier to cooperate with infantry operations. So after putting the lightweight Bren machine gun on the MKI machine gun carrier, the British Army was sure that they had obtained the equipment they needed.

Conclusion

The official name of the Bren machine gun carrier is "Universal Carrier (Universal Carrier) The Bren Carrier was originally called the "Bren Gun Carrier", but people prefer to call it the "Bren Carrier". The car was first equipped by the British Army in 1936, and then widely served in many countries. The total production exceeded 90,000 (other sources say 84,000), and it was used until the 1960s. In World War II, the Bren Carrier not only played a full role, from Europe to North Africa, from Southeast Asia to the Pacific, its figure could be seen everywhere, and it was given a variety of tasks: providing machine gun and mortar fire support for infantry, conducting reconnaissance and search, towing artillery, transporting supplies and wounded, carrying out anti-tank tasks, providing artillery observation, etc. The Bren Carrier has received mixed reviews. Some people praise it as a "panacea", while others think it is simply vulnerable, but it is undeniable that the car is one of the most attractive subcompact armored vehicles in the history of weapons.