It is an ideal to give cruise missiles unlimited range, and people have long placed their hopes on the technical path of nuclear propulsion to realize this ideal, and have made many attempts to do so. In fact, nuclear-powered cruise missiles are an old concept. But old concepts do not mean outdated concepts, and today’s Russia is still obsessed with them. So what is the past and present of nuclear-powered cruise missiles? This is an interesting topic.

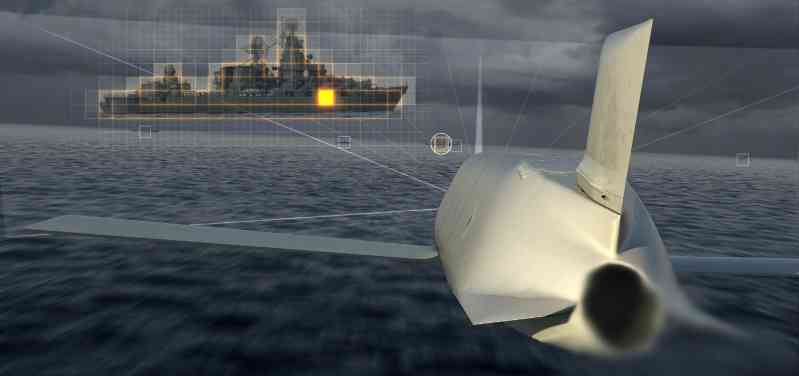

Nuclear propulsion is a form of aircraft power that superpowers have been studying tirelessly since the Cold War. In the 1950s, the United States and the Soviet Union had conducted a lot of related research with the goal of sending nuclear-powered aircraft into the sky and using it as a power system to propel aircraft. In theory, aircraft engines using nuclear fuel can almost allow aircraft to stay in the air for a long time and have unlimited range. Although none of these ideas have entered the stage of practical application, in the 2018 Russian State of the Union Address, Russia made a high-profile exposure of their "Swift" nuclear-powered cruise missile and announced that it would soon begin experiments on the Kamchatka Peninsula. This weapon is said to be able to reach more than Mach 5. Not only is its range unlimited, but it also operates at hypersonic speeds, making it difficult for any defense system to intercept it. Obviously, the ideal of using nuclear power to achieve unlimited range of cruise missiles has never been extinguished in the hearts of Russians...

Starting from the early manned nuclear-propelled aircraft

Since the invention of the airplane, people have hoped to fly higher and farther, across all mountains, rivers, and seas. So in the initial stage of the development of nuclear propulsion technology, the first thing people thought of was to build a nuclear-powered aircraft that would never land.

"Demand is the biggest driving force." The idea of using nuclear power as a power source for large aircraft was proposed as early as 1942: Enrico Fermi, the core scientist of the Manhattan Project and the father of the American atomic bomb, had discussed the possibility of this power with several other scientists.

The project was first launched in 1944. In order to maintain its air superiority over the Soviet Union after the war, the U.S. Army Air Force had conceived an experimental nuclear-powered aircraft project. In the first two years, engineers mainly studied the impact of nuclear radiation on the aircraft platform: its avionics equipment, fuselage materials, and more importantly, the impact on the crew. Initially, the designers were stuck in one technical detail after another. When the project was about to become a pure conceptual design, changes in the situation brought a major turn for the project.

In 1947, the U.S. Air Force, which had just been upgraded from the Army Air Force to an independent military service, was eager to use an unprecedented advanced project to celebrate its birth. The nuclear bomber was the best way to satisfy the imagination of people at that time, and it undoubtedly became the darling of the U.S. Air Force. In 1947, the U.S. Air Force awarded Fairchild Engine and Aircraft a contract to study the feasibility of a nuclear-powered aircraft with an endurance that could be measured in days rather than hours. The study, called NEPA (Nuclear Energy Propelled Aircraft), was conducted at Oak Ridge, Tennessee. In 1948, the Atomic Energy Commission commissioned another similar study at MIT.

The government provided tens of millions of dollars for these two projects. From early 1948 to 1951, research work was carried out in full swing, focusing on reactor technology, power transmission system, and fuselage frame. The power schemes proposed at the beginning were complicated and diverse, with dual reactors, hybrid power (chemical and nuclear), and single power systems all being put on the table. In the end, for the sake of system reliability and safety, the project adopted a single reactor design. Next, the aircraft’s power transmission system was verified, that is, how to convert the heat energy generated by the reactor into the mechanical energy required for flight, which was also the key and most significant technical obstacle to the success of the project.

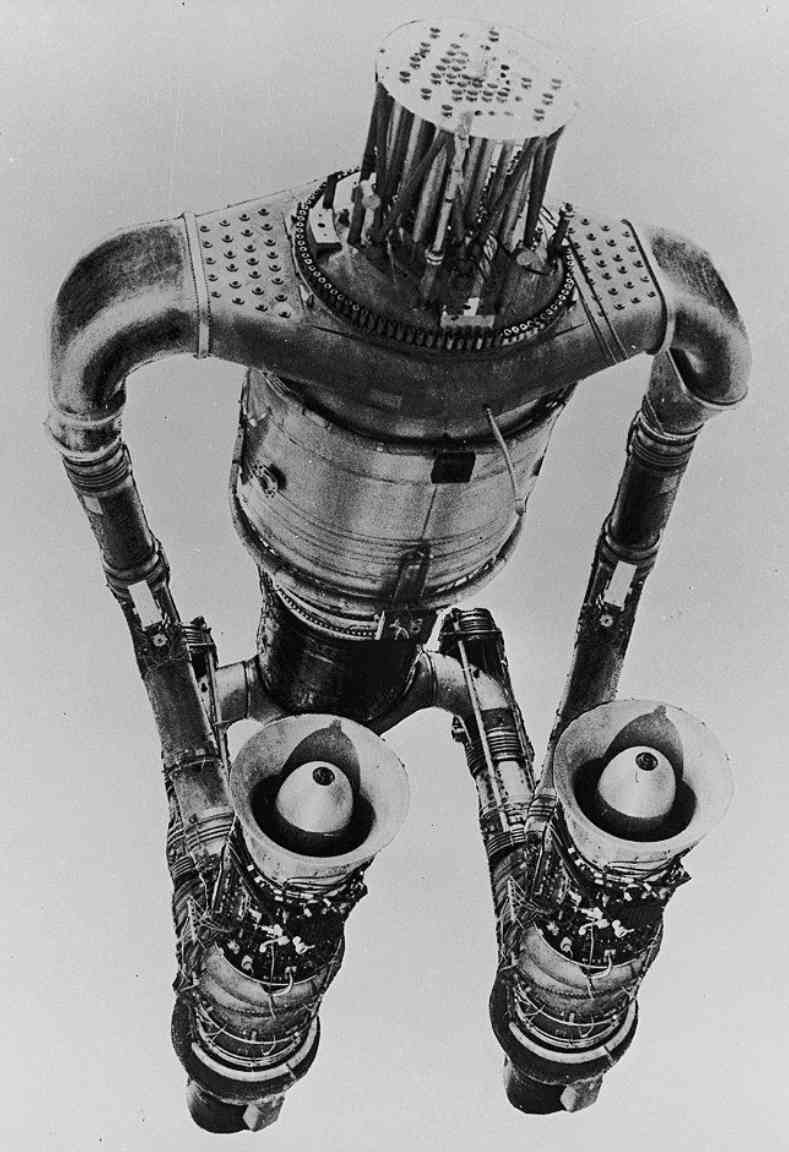

In 1949, the project team tested some nuclear power systems of nuclear bombers, mainly conducting heat transfer tests (HTRE) on three types of reactors to verify the most efficient reactor heat transfer type. After a series of tests, the HTRE-3-nuclear power hot direct cycle engine configuration became the first choice for the project. After the air enters the turbojet engine through the compressor, it enters the core area of the reactor directly through a high-pressure air inlet for heating. In such a structure, high-speed air flow directly serves as the cooling medium of the reactor core to cool the high-temperature liquid metal outside the core; then, the high-temperature and high-pressure gas medium enters another high-pressure zone air inlet, and is distributed to the supercharger turbines of each engine through the diversion of the high-pressure zone; finally, the high-pressure and high-temperature airflow is ejected from the exhaust port or drives the propeller to generate thrust.

This power system is a hybrid power system. The engine uses chemical fuel when the aircraft takes off and lands, and switches to nuclear power after climbing to a high altitude and waiting for the core to reach the nuclear reaction temperature. Another option that has been considered is the nuclear power heat indirect cycle configuration. In this configuration, air does not enter the reactor core directly, but passes through a heat exchanger. The heat energy generated by the reactor vaporizes the working medium (liquid metal or water), and the medium and air exchange energy in the heat exchanger. The air is heated into a high-temperature and high-pressure airflow and directly enters the engine turbine, and then is discharged from the exhaust port to provide power for the aircraft; the working medium cools down in the heat exchanger and returns to the high-temperature core to form a cyclic working state. Of the two options, the designers prefer the direct heat cycle method, which has a simple structure, light weight, and is easy to manufacture; more importantly, there is not much time left for the project team, and the direct cycle also meets the design requirements, so it was adopted.

After determining the power and energy transmission form of the aircraft, the designers began to study how to shield the impact of nuclear radiation on the crew and avionics equipment. The initial plan imitated the protection of ground nuclear reactors, and used cadmium, solidified paraffin, beryllium oxide and steel plates to make protective layers in turn. The idea is to focus on the protection of the reactor, while no protective measures are taken for the crew and avionics equipment on the same aircraft. Technically, this is a robust traditional method, but when the aircraft is on the ground and in the air, the rapid changes in the core environment, such as low pressure, vibration, acceleration, etc., will make this protection no longer reliable. Later, based on the comprehensive consideration of protection and performance, it was decided to adopt multiple protection technology. After adopting this technology, the protection of the whole aircraft is divided into two parts, and the core compartment and the crew compartment are protected at the same time, that is, the protection weight of the core compartment is greatly reduced, and the protection of the crew compartment is strengthened. Even if there is a leak in the core, the safety of the crew can be guaranteed to the maximum extent. In early 1951, the US Air Force concluded that the research results of NEPA have clearly indicated that it is possible to start developing actual nuclear propulsion devices. In 1954, the US Air Force decided to start manufacturing an actual nuclear-powered aircraft, the project name is WS-125A. Pratt & Whitney and General Electric were selected as the main engine contractors at the same time, and Lockheed and Convair were responsible for manufacturing the fuselage.

WS-125A is a high-altitude subsonic bomber, but it will have supersonic cruise capability in the future. As part of the project, engineers need to test the effects of reactor radiation on aircraft instruments, equipment, and fuselage, and study corresponding shielding measures. To this end, the Air Force allocated a B-36H strategic bomber prototype 51-5712 to the project for radiation testing on May 11, 1953.

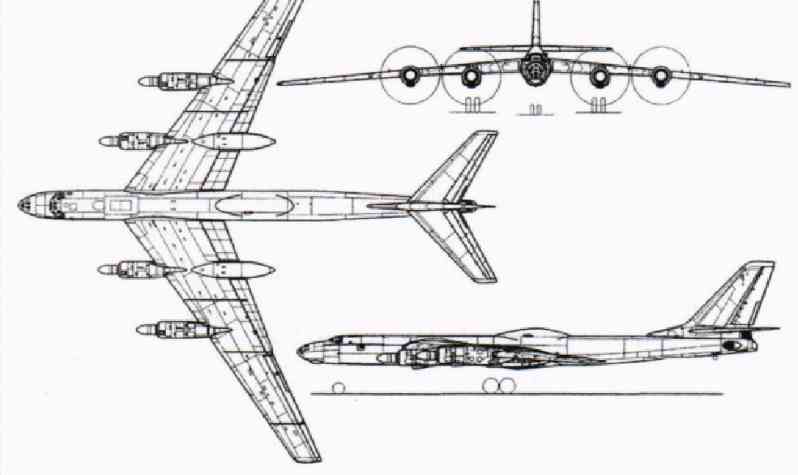

B-36 is indeed a giant among large aircraft, and it is not much inferior even to the large transport aircraft in service. B-36 adopts a slender cylindrical fuselage, a cantilevered upper monoplane straight wing, 6 piston engines, and propellers installed on the trailing edge of the wing, making it a pusher aircraft. In some modifications, two jet engines are also hoisted under each wing. The wing has a relatively large span, an all-metal structure, a reinforced skin, a leading edge sweep angle of 15.7 degrees, and an electrically controlled trailing edge flap. The fuselage of the aircraft is an all-metal structure with a circular cross-section. There is a transparent nose cover at the front of the fuselage, which is set as the crew cabin, and the bomb bay is in the middle and rear of the fuselage. The wingspan of the B-36 is 70.1 meters, the length is 49.38 meters, the height is 14.02 meters, the main wing area is 443.3 square meters, and the take-off weight reaches 185.97 tons; the ceiling of the B-36 is 12,000 meters, the climb rate is 676.65 meters/minute, the maximum speed is 700 kilometers/hour, and the range is 16090 kilometers. All these performances are enough to make it the only choice for future nuclear-powered bomber carriers. The reason why the 51-5712 aircraft was used was that on September 1, 1952, 51-5712 was severely damaged by a tornado that swept through the Carswell Air Force Base. The Air Force felt that instead of repairing the severely damaged nose, it would be better to directly allocate the aircraft to Convair for radiation testing.

Engineers installed a nuclear reactor with a design power of 1,000 kilowatts and a weight of 15,876 kilograms in the rear bomb bay of 51-5712. Of course, this reactor is not the power unit of the aircraft, but only a radiation source, which can be removed as a whole on the ground by a crane. In order to cool the reactor, the B-36H opened a series of large air intakes and exhaust ports on both sides and below the rear fuselage. The crew of the aircraft was 5 people, including the pilot, co-pilot, flight engineer and 2 nuclear engineers, all sitting in the highly shielded crew cabin in the nose. The crew cabin was tightly wrapped with thick layers of lead and rubber, and the windshield was also 30 cm thick leaded glass. In addition, Convair also installed a 4-ton lead shield in the middle of the fuselage, and the aircraft was equipped with a closed-circuit television system for the crew to monitor the reactor.

51-5712’s engine adopts a hybrid configuration, consisting of 4 turbojet engines and 6 piston propeller engines. After the modification, the power system was adjusted as follows: the propeller power was changed to 4 General Motors J47s, which were driven by nuclear reactor energy and had a single power of 3,800 horsepower; 4 turbojet engines, each with a thrust of 5,200 pounds. Each engine uses the energy of the reactor through a set of core heat energy direct circulation systems. Of course, the aircraft also carries a considerable amount of fuel for takeoff and landing, or when the reactor is abnormal. After the modification, the number of 51-5712 was changed to XB-36H, nicknamed "Crusader"

The first flight of the Crusader was on September 17, 1955, with A.S. Witcher Jr. as the test pilot. For safety reasons, all test flights of the aircraft were conducted in sparsely populated areas, and the reactor was not turned on until the aircraft climbed to a safe altitude. Every test flight of the XB-36H was accompanied by a C-97 transport plane, which carried a platoon of Marines. In case the XB-36H crashed, they jumped down and risked their lives to block the crash site...

XB-36H The project was kept secret until the end of 1955 when the US Department of Defense acknowledged the existence of the B-36 nuclear test aircraft. In the fall of 1956, the number of the XB-36H was changed to NB-36H. Although the nuclear reactor did not operate at full capacity to propel the aircraft in the limited test flights, the experiment verified that this power could indeed be used for long-duration flights of aerial platforms. However, the Air Force decided to cancel the WS-125A project for practical considerations (the main reason was that the test results showed that the radiation had too much impact on the health of the crew and on the onboard electronic equipment, and it had lost the significance of further demonstration). On March 28, 1957, the NB-36H made its last flight, and so far it had flown 47 sorties. At the end of 1957, the NB-36H was retired in Fort Worth, and was dismantled a few months later, and the radioactive parts were buried deep. While the United States was conducting nuclear-powered aircraft tests, the Soviet Union had similar plans. In 1955, the US Air Force publicly acknowledged that the WS-125A nuclear-powered aircraft project did exist, which gave the Soviet Union a great stimulus. At the instruction of Khrushchev, the then supreme leader of the Soviet Union, Resolution No. 1561-868 on a strategic bomber powered by a small nuclear reactor was passed. The content of the meeting No. 1561-868 was that the Tupolev Aircraft Design Bureau and the Myashev Aircraft Design Bureau were responsible for developing a brand-new nuclear-powered strategic bomber.

Like their American counterparts, Soviet designers initially used the hot direct cycle as the energy transmission mode for future airborne reactors; the difference is that the Soviet Union did not focus entirely on the energy transmission cycle, but instead tested more types of engines, including ramjet engines, propeller engines, turbojet engines, etc., all of which were tested with nuclear power. After a large number of screening tests, it was finally determined that the hot direct cycle mode with turbojet engines combined with nuclear power would be the power composition of future aircraft. In the Soviet design, after the air enters the turbojet engine inlet, it is compressed by the compressor to become high-pressure gas, and then guided to the core area through a high-pressure gas chamber. These gases will be directly heated as the cooling medium of the core; after that, the high-temperature, high-pressure gas reaches another high-pressure gas chamber and is diverted to each jet engine to drive the turbine to generate thrust. Subsequently, considering that the US Air Force had already started experiments on the existing B-36 bomber, in order to ensure the progress of the project, the Soviet authorities decided to develop a nuclear-powered bomber based on the Tu-95 "Bear" long-range strategic bomber.

Since the Tu-95 "Bear" strategic bomber was developed by the Tupolev Design Bureau, the responsibility of developing a nuclear-powered bomber naturally fell on the Tupolev Design Bureau. Tupolev began to improve the Tu-95 "Bear" strategic bomber again, mainly to be able to put the nuclear reactor into the fuselage of the bomber. The Soviet Atomic Energy Research Institute, which was responsible for developing a small nuclear reactor, was also repeatedly testing the small nuclear reactor.

In 1958, the Tupolev Design Bureau successfully installed a small nuclear reactor on the Tu-95M bomber and made its first flight as the Tu-95LAL model. In early 1958, the aircraft completed various modifications and was ready to be loaded with a nuclear power unit for ground testing; in the summer of that year, the carrier aircraft and the nuclear power unit successfully completed the ground startup test, and the core successfully reached the predetermined power, which paved the way for the next stage of air test startup. From May to August 1961, the Tu-95LAL conducted a total of 34 research flights, with many test pilots, designers, engineers and physicists participating in the tests. During these test flights, the nuclear reactor was not turned on for most of the time, and the main purpose of the flight phase was to check the reliability of the nuclear device shielding system. As for the composition of the shield, it is the same as that of the Americans: beryllium oxide, cadmium, solid paraffin and steel plates. In the nuclear protection of the crew members, it once again showed that the United States and the Soviet Union were similar in technology. In addition to focusing on the protection of the core, Soviet designers also made important protection for the crew cabin, reducing the radiation level in the crew cabin to an acceptable level.

Based on the Tu-95LAL, the Tupolev Design Bureau designed and built a second nuclear-powered propulsion prototype, code-named 119 (i.e. Tu-119). Compared with the first prototype, the main difference of this aircraft lies in the four engines of its fuselage: it is equipped with a new NK14a turboprop engine equipped with a heat exchanger, while the two NK12MS engines remain unchanged. When the No. 119 prototype was designed, the Kuznetsov Design Bureau also intensively launched the development of engines using nuclear energy. The nuclear reactor is located in the ammunition compartment in the middle and rear part of the fuselage. The heat released by the reaction is pressurized and heated through a direct circulation system, and then transmitted to each engine through connecting pipes. Tupolev estimated that the No. 119 prototype would have to be tested in 1965 at the earliest. After the test is completed, the ignition of the No. 119 prototype will be replaced with four NK14a engines developed by the NK Kuznetsov Design Bureau. Later, this modified bomber was also called the Tu-119 "Swallow" nuclear-powered strategic bomber, and Khrushchev described the aircraft as the "Never Tired Swallow"

During the development of the "Swallow", the nuclear reactor high temperature and nuclear radiation problems were also encountered. The nuclear reactor will become hot after about an hour of use. The United States adopted an air-cooled solution, while the Soviet Union adopted a combination of water cooling and air cooling to cool the nuclear reactor, including liquid sodium on nuclear submarines as a coolant. A huge water tank was also designed for the "Swallow" to deal with emergencies in the heat dissipation of the nuclear reactor. In order to reduce the nuclear radiation to the crew, the designers wrapped the nuclear reactor heavily with metal and installed a thick isolation door in the cab.

Unfortunately, the strong nuclear radiation from the nuclear reactor of the "Swallow" caused serious damage to the aircraft during the test. Although the designers heavily shielded the nuclear reactor and put on multiple layers of metal shells, the weight of the fuselage also increased, but the problem of nuclear radiation was still not solved. Since the nuclear radiation problem has never been properly solved, after the "Swallow" has been tested for more than 60 times, the Soviet government decided to terminate the nuclear-powered bomber project.

In the summer of 1955, the Miashev Design Bureau also launched a nuclear-powered aircraft project at the same time as the Tupolev Design Bureau. On May 19 of the same year, the Soviet Council of Ministers ordered the design bureau to conduct preliminary research and named it the M-60 prototype. The first design sketch of the M-60 was completed in July of the following year; at the same time, the development of the new engine of the Lyulka Design Bureau was also launched at the same time, with a planned thrust of 49,600 pounds. Like the NB-36, the M-60 also uses chemical fuel during takeoff and landing, and only turns on the nuclear reactor during the air stabilization phase to cruise at twice the speed of sound. The nuclear reactor is deployed at the tail of the fuselage, and the crew cabin is wrapped with radiation-proof heavy metals and neutron-absorbing materials. The carrier aircraft adopts a brand-new design, with trapezoidal wings, a slender fuselage, a T-shaped tail, and air intakes and four engines on both sides of the fuselage; in order to reduce the impact of nuclear radiation on the crew, the engines are divided into upper and lower layers and installed side by side in the isolation cabin at the tail of the aircraft. Missiles and bombs are directly installed on the suspension and deployed inside the cabin. The entire aircraft is expected to be 51.51 meters long, with a wingspan of 26.21 meters, and the landing gear is a conventional three-point type. The speed of the aircraft exceeds 2 times the speed of sound, the range is 25,000 kilometers, and the practical ceiling exceeds 20,000 meters. But unfortunately, the M-60 has never been manufactured. However, even so, the technical achievements and lessons learned by the United States and the Soviet Union in nuclear-powered aircraft were put to use in the subsequent nuclear-powered cruise missile project.

Turning to nuclear-powered unmanned aerial vehicles - "Pluto Project" and SLAM cruise missiles in the early Cold War

The idea of cruise missiles actually existed as early as the beginning of the 20th century, almost as long as the history of military aviation. In 1915, the American Sperry Company proposed the idea of "flying torpedo" - using a gyroscope to control the flight of a small aircraft. Later, the United Kingdom also proposed a similar idea: the "Larynx" missile was developed and launched on the Royal Navy’s "Fortress" battleship in 1927. However, the above attempts did not persist in the United States and Britain. Only the US Navy continued to develop propeller-driven cruise missiles until World War II, but their research results could not be compared with Germany in terms of quantity or quality.

In contrast to Britain and the United States, Germany, the defeated country in World War I, attached great importance to this concept and persisted in research: Research on cruise missiles in Germany began as early as 1936, when Fritz Goslo, a scientist employed by Argus, began to study the feasibility of developing remote-controlled aircraft. At that time, Argus had developed a remote-controlled aircraft-AS.292 (military number FZG43) and delivered it to the army as a target aircraft. On November 9, 1939, a more mature unmanned aircraft design was rushed out and submitted to the Third Reich Aviation Ministry (RLM). According to this plan, the aircraft can carry a payload of 1,000 kg and fly 500 kilometers, but this plan was not taken seriously at the time. After all, World War II had already broken out, and limited productivity had to be given priority to more urgent needs-Bf109 fighters, Bf110 twin-engine fighters and Ju88 bombers, etc. Later, Argus and two other companies, Lorenz and Arado, jointly established a joint venture, Fesler Aircraft Manufacturing Company, to continue research and development in this area. Its most important achievement was the first practical cruise missile in human history.

V-1. The design purpose of V-1 is very simple, that is, to attack the British capital of London. On June 13, 1944, one week after the Allied landing in Normandy, V-1 took off from a launch site codenamed "Ski" (this word means "skateboard" in both French and German) deployed on the coast of France and the Netherlands to attack London. In the first round of launch peak, a total of 9,521 V-1s were launched. In October 1944, with the Allied offensive, the first-line launch sites in Germany were successively occupied, so V-1 began to move positions and attack Allied targets in Antwerp, Belgium and other places. A total of 2,448 missiles were launched in the second round of launch peak. As the first practical cruise missile in human history, the design of all human cruise missiles in the future has more or less the shadow of V-1. But what’s interesting is that as the originator of practical cruise missiles, V-1 has been plagued by insufficient range since the beginning.

The theoretical range of V-1 is only 370 kilometers. Therefore, its combat effectiveness depends on the layout and construction of the launch site. On June 18, 1943, Nazi German Air Force Marshal Goering held a special meeting to discuss deployment issues. The final plan was to deploy 96 launch sites along the English Channel. The 96 launch sites built along Dieppe to Calais, each launch site includes a launch rail with protective walls on both sides; a non-magnetic machine room for debugging magnetic compasses, a launch shelter, ammunition depots for storing missiles, fuel storage rooms and other warehouses. In addition, only 8 launch sites were built in Normandy. There was originally a larger plan: to build more launch sites along the coast of Cherbourg to Belgium, but it was too late to implement it. Most of the V-1s fired at London were fired from these launch sites deployed along the English Channel.

However, after the Allied landing in June 1944, the cruise missile launch sites deployed on the French coast fell one after another, and the range of V-1 was no longer enough to hit London, so it was changed to air launch carried by bombers. Because the air launch platform is flexible and concealed, it can not only effectively avoid the attack of the Allied ground forces, but also avoid the resistance of the British air defense forces. In order to reduce the probability of being discovered by British radar when launching V-1, German bomber pilots later invented a tactic called "low-high-low", specifically: after taking off, the He111 bomber carrying V-1 will descend to the lowest possible altitude after flying over the coast and entering the sea; when approaching the launch position, the bomber quickly climbs to the predetermined altitude and launches the missiles carried; after completing the launch mission, the bomber turns around and quickly lowers the altitude again, repeating the previous steps to return at low altitude. However, this does not completely solve the problem. The reliability of the air-launched V-1 was very poor. After the war, scholars estimated that about 40% of the air-launched V-1 launches failed. Moreover, for the bombers carrying out the launch mission, such a mission was also very dangerous. In the first few seconds of each launch, the missile tail flame would illuminate the surrounding night sky, which was tantamount to pointing out a good target for the enemy night fighters. Therefore, the fundamental solution was to find a way to increase the range.

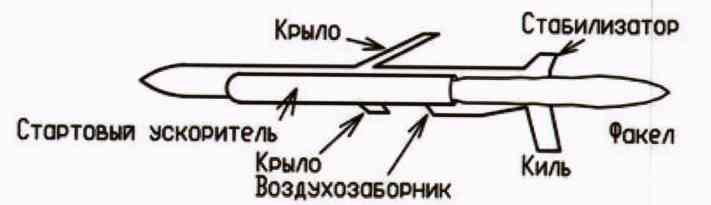

After June 6, 1944, with the opening of the "Second Front", the German launch sites in France fell one after another, and the area of the German-occupied area continued to shrink, which meant that the V-1 would soon be unable to attack targets in Britain due to insufficient range. So the V-1F1 missile came into being: the problem was solved by increasing the fuel tank volume of the V-1 and reducing the warhead charge. In addition, in order to reduce the weight of the missile body, the nose cone of the missile head was made of wood. After these changes, the V-1F1 could finally hit London and its surrounding areas from the Netherlands. The German High Command originally planned to mass-produce and deploy this extended-range V-1, hoping that it could play a role in supporting the front battlefield in the subsequent Ardennes Forest counterattack, but the bad situation at the time (missile production plants were constantly bombed by the Allies, strategic materials such as steel were in short supply, railway transportation capacity was tight, the battlefield situation was deteriorating, etc.) greatly delayed the deployment of the extended-range missile, and it was not until February-March 1945 that this missile was just beginning to be deployed. Before V-1 ended its air raid on London at the end of March, the German army launched hundreds of extended-range missiles from a launch site in the Netherlands... After Nazi Germany surrendered, the technical data and some physical objects of V-1 were divided up by the United States, the Soviet Union, Britain, France and even Sweden, becoming the basis or reference for each country to independently develop its own cruise missiles in the future. France developed the CT-10 (also known as Arsenal 5501) target missile based on V-1, which is slightly smaller than V-1, but equipped with two vertical tails. It can be launched from the ground with the help of rocket boosters, and of course it can also be launched from the air. Some of the CT-10s were sold to the United States and Britain. After occupying the German rocket test base in southeastern Poland, the Soviet army seized the V-1 stored there and copied the 10Kh cruise missile based on it. The initial launch test of 10Kh was carried out in Tashkent, the capital of the Uzbek Soviet Union, in March 1945, and further ground and air launch tests were carried out in the late 1940s.

In June 1944, the United States began to reverse-engineer its own jet cruise missile system based on the V-1 wreckage it obtained in the UK. On September 8 of that year, the first batch of 13 American V-1s, Republic-Ford JB-2 (JB is the abbreviation of jetbomb in English, meaning jet bomb, which was a guided weapon research and development project conducted by the US military during World War II. A total of ten weapons were developed, numbered from JB-1 to JB-10) missiles began to be assembled at the Republic Aircraft Manufacturing Company in the United States. Compared with the V-1, the JB-2 has a similar appearance and structure, but is slightly smaller in size. In addition, the Navy also developed its own ship-borne missile system based on the V-1 missile, the KGW-1 system. The system is planned to be launched from LST tank landing ships, escort aircraft carriers, and PB4Y-2 long-range bomber/patrol aircraft. In addition, the US military also plans to use submarines to launch this type of missile (specifically, submarines carry missiles to the enemy’s coastal waters, and then surface to launch missiles). For this purpose, a submarine sealed launch device loaded with missiles has been specially developed. Both of the above missiles have been put into production, and the output is not small: the first batch of JB-2 missiles is planned to produce 1,000 missiles, and the total planned production is 75,000 missiles. In order to meet this production capacity requirement, Republic even planned to convert a production line that originally produced P-47 fighters to produce JB-2 missiles; Ford Motor Company and Willys planned to produce IJ-15-1 pulse jet engines that imitated the V-1 engine.

Originally, the U.S. military planned to use them in the campaign to attack the Japanese mainland, but the plan failed as the U.S. military dropped two atomic bombs on Japan and Japan announced its unconditional surrender. In the process of developing more advanced ground-to-ground tactical missile systems in the United States after the war, JB-2/KWG-1 played an important role: JB-2 was carried by B-17, B-29 and B-36 bombers for air launch tests; KWG-1 was launched on the U.S. Navy "Cusk" submarine in 1951. Inspired by this, the U.S. military began to attack larger, longer-range and more complex cruise missiles. In August 1945, the U.S. Army Air Force ambitiously launched a series of ground-to-ground cruise missiles, one of which was to develop a large ground-to-ground cruise missile with a cruising speed of 1,000 kilometers per hour, a range of more than 8,000 kilometers, and a warhead weight of about 800 kilograms.

In January 1946, Northrop Corporation launched a subsonic cruise missile with a range of about 5,000 kilometers, which was propelled by a turbojet engine and nicknamed "Snake Shark". Soon, Northrop received a contract to develop this missile. The contract stipulated that the company must develop two models of this missile within one year. From 1947, the development of the SM62 cruise missile started. Initially, two types of missiles were mainly developed, one was a supersonic cruise missile, code-named MX775B, and the other was a subsonic cruise missile, which was transformed into MXJ75A. The military budget was cut in the Christmas of 1946, and the subsonic version was eliminated, but the supersonic model was retained. Jack Northrop, the head of Northrop Corporation, contacted Air Force Commander Carlsbets and other important officials of the Air Force through personal connections. Northrop promised them that the annual production of missiles could reach 5,000 within two and a half years, and the unit price of each missile would be controlled below $80,000. For a missile that can fly intercontinentally, this is a very tempting condition.

Under Jack Northrop’s strong persuasion, the US Air Force finally agreed to continue development, but asked Northrop to modify the original design details. In late 1947, the number of "Snake Shark" was changed to SSM-A-3, and the missile officially entered the engineering development stage. The Air Force Equipment Command required that "Snake Shark" be launched in March 1949 and conduct more than 10 launch tests within the year. The weight of this missile is 27.2 tons, the weight without booster is 21.8 tons, the wingspan is 12.9 meters, and the total length is 20.5 meters, which is nearly twice the length of the 11.4-meter-long F-86 fighter. The most proud feature of the "Snake Shark" cruise missile is that its maximum range reaches 10,000 kilometers. If deployed in the United States, it can also strike the Soviet Union. Even from today’s perspective, this range is very far, even exceeding many intercontinental missiles in history.

The maximum speed of the Snake Shark cruise missile is 1050 kilometers per hour, and it takes nearly 11 hours to reach the target. That is to say, the operator launched the missile at 10 o’clock in the evening and went to bed. When he got up the next morning, the Snake Shark was still flying! The Snake Shark began to conduct launch tests at Herman Air Force Base in 1950, but the first launch in December ended in failure. After careful preparation, the Snake Shark was finally launched successfully in April 1951. The missile flew in the air for 38 minutes. During this period, Northrop Grumman manufactured a total of 16 missiles. Because the missile was equipped with a recovery device, the launch team used these 16 missiles for 21 launch tests. In the last launch test, the maximum flight speed of the Snake Shark reached Mach 0.9, and the missile flew in the air for 2 hours and 45 minutes.

In 1958, the US Air Force Strategic Command began to accept SM62 missiles, and the first was equipped with the 702 Strategic Missile Wing. A total of 30 missiles of this type were deployed. However, the US Air Force was not satisfied with the "Snake Shark", so it began to withdraw it only half a year after it was put into service. The reason for this is that in addition to the poor guidance accuracy, the speed and altitude of the "Snake Shark" missile are closer to high subsonic jet bombers, which are easy to intercept.

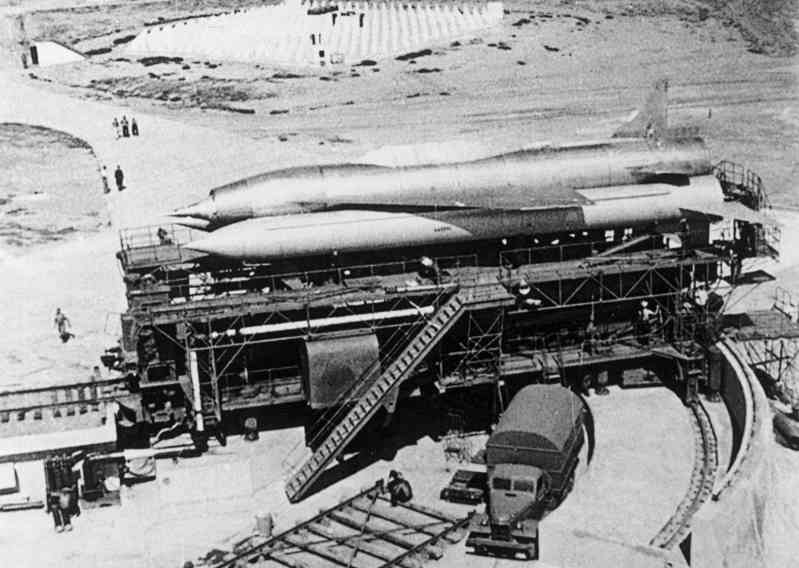

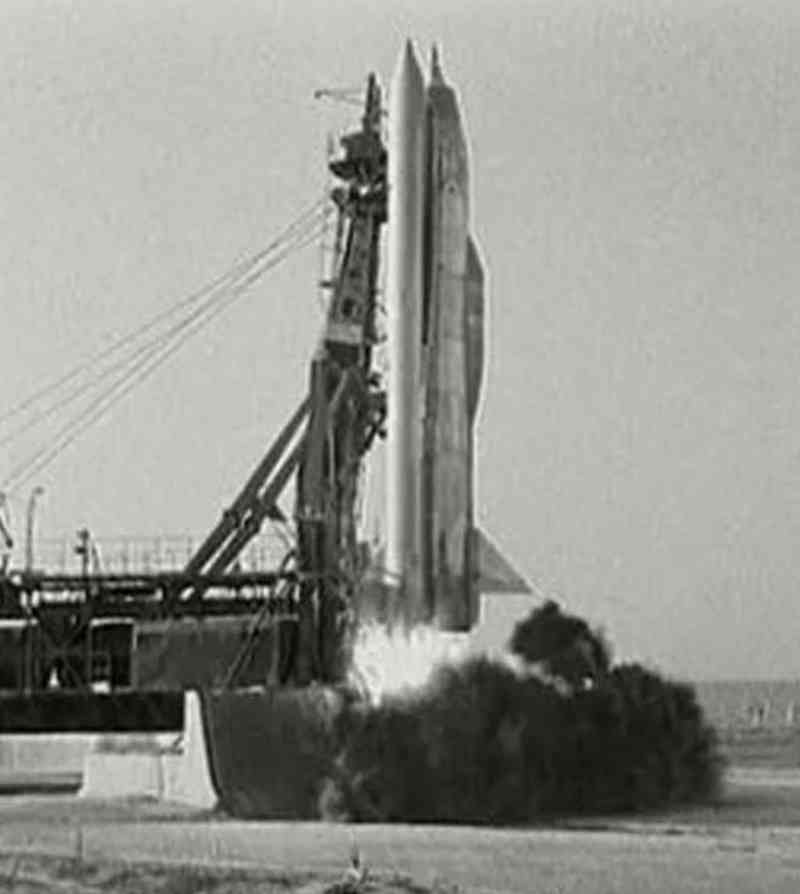

The same problem also exists in several types of intercontinental cruise missiles developed by the Soviet Union at the same time. Take the La-350 "Storm" intercontinental cruise missile designed by the Lavochkin Design Bureau as an example. In 1954, the Soviet Union launched the research and development of intercontinental cruise missiles. First, the overall structure of the missile was roughly determined. The missile is somewhat similar to the later space shuttle. It is divided into two basic parts, namely the carrier rocket and the missile body. The initial design of the Lavochkin Design Bureau took only a few months to submit the plan in August of that year. The relevant departments proposed modification requirements for some details of the missile, such as increasing the weight of the missile’s warhead to 2.35 tons, which was directly related to the size of Soviet nuclear weapons at the time.

The carrier rocket of the La-350 "Storm" cruise missile has two large boosters, each of which can accommodate 6,300 kg of fuel and 20,840 kg of oxidizer, and a four-chamber S2.1100 engine at the end (later replaced by an S2.1150 rocket engine). The booster is 18.9 meters high and 1.45 meters in diameter, and can generate 68.61 tons of thrust. The engine has a control rudder that can adjust the flight attitude during flight. The missile body with wings is tied to the booster. The missile itself is driven by an RD-012U ramjet engine. This engine cannot be started at rest or at low speed. It ignites when the booster rocket sends the missile to an altitude of about 17,500 meters. The engine air intake is located at the front end of the missile. The fuel tank is located between the shell and the inner wall of the air intake. The back of the missile is a structure that looks like a cockpit. In fact, it is equipped with navigation equipment and cooling equipment. The missile shape follows the aerodynamic shape required for the cruising altitude. It has a long delta wing with a leading edge swept back 70 degrees and an X-shaped rudder at the tail. In order to launch the "Storm", a special launch platform needs to be built. Just like the conventional space rocket launch mode, the missile needs to be turned to a vertical position and then the launcher is rotated in the correct direction.

The overall structure of the "Storm" cruise missile is huge and bloated. Its launch weight is 96,000 kilograms and its total length is 19.9 meters. The missile’s flight altitude is between 18 kilometers and 25.5 kilometers. The cruising speed is 3.1 Mach to 3.3 Mach, and the maximum can reach 3.5 Mach. The combat range is 8,000 kilometers to 8,500 kilometers. It carries a 2,190-kilogram nuclear warhead and the missile error is within 9 kilometers. As a backup for the La-350 "Storm" cruise missile, the Soviet government also commissioned the Myasishchev Design Bureau to design another M-40 "Buran" intercontinental cruise missile. Although the two missiles are basically the same in terms of main structure, both use rocket engines as the first stage and dual-mode scramjet engines for the second stage, but the two design bureaus still have many differences in specific designs. The first stage of the "Storm" uses two S2.1150 rocket engines with a thrust of 686.1 kN each, while the "Buran" uses four RD-213 rocket engines. This type of rocket fueled by liquid oxygen and kerosene has a relatively small thrust, with a single thrust of 550 kN. Their size and weight are even more amazing. The length of the "Storm" is 18 meters, the diameter is 2.2 meters, the wingspan is 7.75 meters, and the wing area is 60 square meters. The "Bullid" is even more powerful than the Storm, with a length of 23.3 meters, a diameter of 2.4 meters, a wingspan of 11.6 meters, and a wing area of 98 square meters. In front of them, the American "Snake Shark" and "Navajo" can only be regarded as little guys. The take-off weight of the "Storm" has reached 96 tons, and the "Bullid" is even worse. The take-off weight of 125 tons makes it more like a large bomber.

However, in the late 1950s, both the smaller "Storm" and the larger "Burn" stopped developing. The main reason was that the high flight altitude made the cruise missile’s penetration capability poor. If the flight altitude was lowered, the range of "Storm" and "Burn" would be greatly reduced, which was unacceptable to the Soviet government. After all, the Soviet Union’s overseas military bases were far inferior to those of the United States. In order to cross the Arctic Ocean and strike the US mainland, the requirements for the range of intercontinental cruise missiles were higher than those of the United States. So how to solve the contradiction between penetration and range? Nuclear propulsion naturally came into people’s minds.

Cruise missiles are disposable unmanned aircraft. Since they are unmanned, there is no need to consider the radiation shielding of the crew. Therefore, the feasibility of combining the contradictory factors of low altitude, high speed and long range is greatly increased. So after the failure of the nuclear-powered aircraft test, the Americans realized that the high dose of radiation from nuclear-powered aircraft determined that it could only be unmanned, and the best specific application was the low-altitude, high-speed, long-range intercontinental cruise missile with high penetration capability.

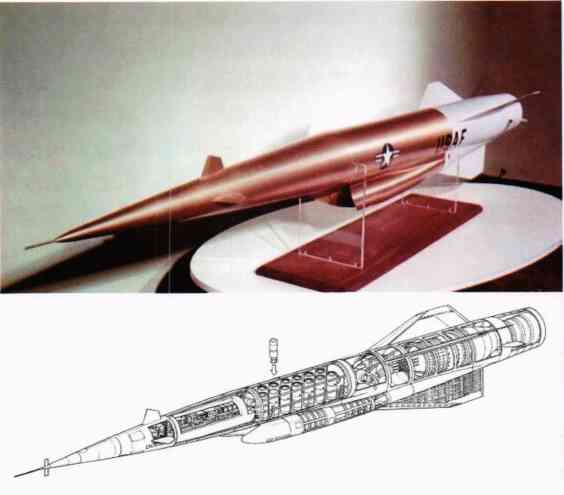

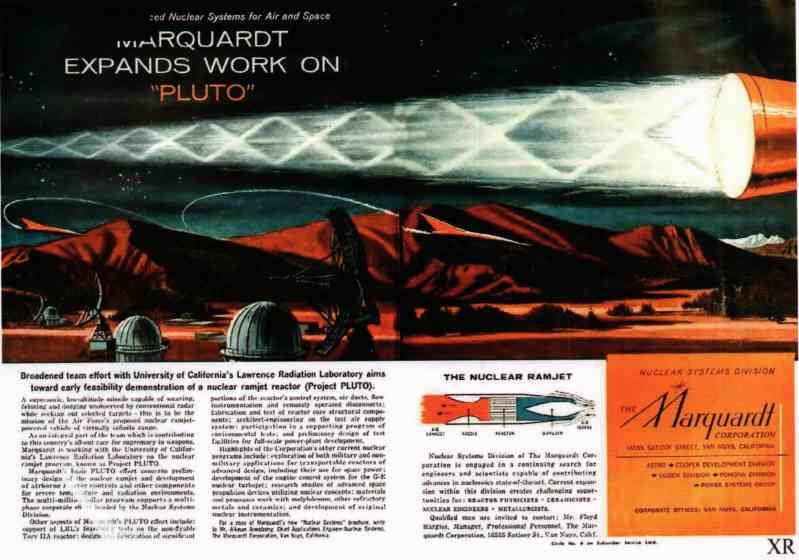

In 1957, the U.S. Air Force and the U.S. Atomic Energy Commission launched the "Pluto" nuclear power program and the nuclear-powered cruise missile project called "Supersonic Low Altitude Missile.SLAM". As mentioned earlier, the U.S. military has been paying attention to the development of nuclear-powered aircraft (NEPA nuclear-propelled aircraft). In 1955, the U.S. Strategic Capabilities Office (SCO) consulted the Nuclear Energy Commission on the feasibility of the concept of nuclear-propelled missiles. In October 1956, the changes in the world situation led the US Air Force to issue a requirement for a nuclear-powered winged missile system (SR#149). In 1957, the US Air Force and the US Nuclear Energy Commission selected the Lawrence Radiation Laboratory of the University of California to begin a feasibility study on a nuclear-powered ramjet engine. This power project was the "Pluto Project".

The purpose of the "Pluto Project" was to develop a nuclear-powered ramjet engine. The so-called ramjet engine directly uses the power of the vehicle’s high-speed flight to inject a large amount of air into the engine’s air intake and use its own speed to complete compression without the need for turbines and other equipment, and then mix the compressed air with fuel to ignite to generate thrust. As for how this principle is related to nuclear power, this is the key to the problem. In fact, the principle of this nuclear-powered ramjet engine is not complicated: when the missile is flying at high speed, the front airflow will enter from the air intake under the action of the ramjet effect. At this time, if the airflow is allowed to flow through the nuclear reactor, the amazing heat released by the nuclear reaction can be used to quickly heat the air, allowing it to expand at high speed and be discharged from the nozzle to generate forward propulsion.

The idea is simple, but the challenges of engineering practice are extremely difficult. Since it is installed on a missile, this nuclear-powered ramjet engine cannot be wrapped in a thick concrete shell like a civilian nuclear reactor. Instead, it must be compact and light enough, and must meet the requirements of continuous flight of tens of thousands of kilometers. The longevity of nuclear-powered engines allows missiles to fly continuously for several months, so that the missiles can stay in the air for a long time to "cruise" and wait for the final target confirmation and attack instructions. Because the nuclear reaction lasts long enough, in theory, this engine can support the aircraft to fly anywhere in the world. The engine working environment of the "Pluto Project" is very harsh. Low-altitude and high-speed flight requires the engine’s reactor to maintain high temperature and strong radioactivity. Generally, the materials used to make the engine will melt. Essen Pratt, an engineer on the project, said, "The Pluto Project is close to the limit." In order to achieve the projection capability beyond manned nuclear bombers and ballistic missiles, the design of the "Pluto Project" must be simple and reliable. In the words of the project engineer, it is "as durable as a bucket of stone." Technical Director Ted Meikle nicknamed the project "Flying Crowbar"

In fact, the "Pluto Project" posed extremely harsh challenges to the metallurgy and materials science of the United States at that time. The pneumatic motors required to control the reactor must work stably in a high-heat and high-radiation environment, otherwise the flight status of the missile cannot be guaranteed. Since the purpose is to enable the high-penetration low-altitude supersonic intercontinental cruise missile to achieve all-weather low-altitude supersonic flight, the nuclear reactor power of the Pluto Project is 513 megawatts, code-named Tory. The entire reactor has no shielding design, and the core contains 500,000 hexagonal beryllium oxide ceramic nuclear fuel rods. In order to work at 1600 degrees Celsius, the project team specially made 500,000 pencil-sized ceramic nuclear fuel rods for the missile nuclear reactor from Coors Ceramics in Colorado. In order to resist rain and snow during flight and salt in the air, the project team also tested various materials to make reactor corrosion-resistant substrates. Even the probes for testing material temperature were newly developed. Generally, thermal probes would be destroyed by the high-temperature radiation of the reactor.

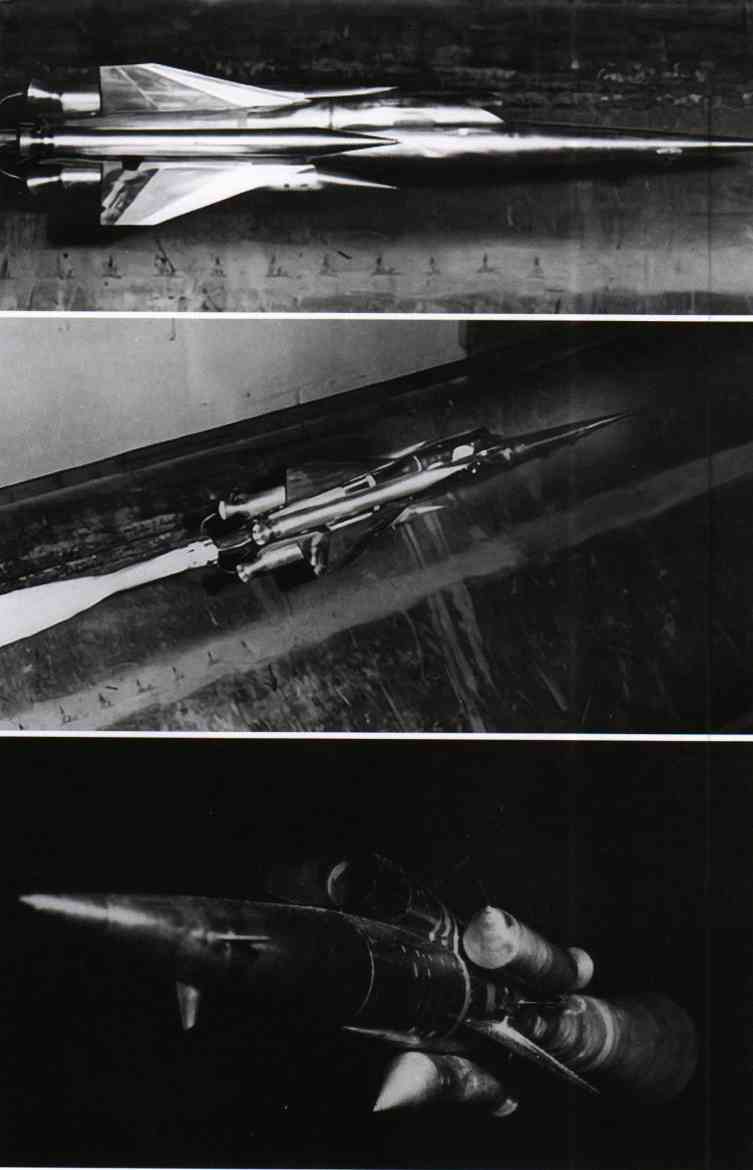

As for the SLAM nuclear-powered cruise missile project, it is an ultra-low-altitude 3 times supersonic intercontinental cruise missile, which uses the technical achievements of the "Pluto Project" to achieve unlimited range at 3 times the speed of sound at treetop height. SLAM is actually a nuclear power + ramjet configuration in structure. Due to the working principle of the ramjet engine, it is almost impossible to work stably when it is less than Mach 3. This missile needs to be bundled with 3 more rockets. When the aircraft accelerates to Mach 3, the ramjet engine is turned on and the rocket is thrown away. However, since ramjets often operate at speeds above Mach 3, how can they cruise at ultra-low altitudes? So in fact, the design indicator of SLAM is set at an altitude of about 35,000 feet. In the era when intercontinental ballistic missiles were not yet mature, this was obviously an ideal strategic nuclear weapon solution.

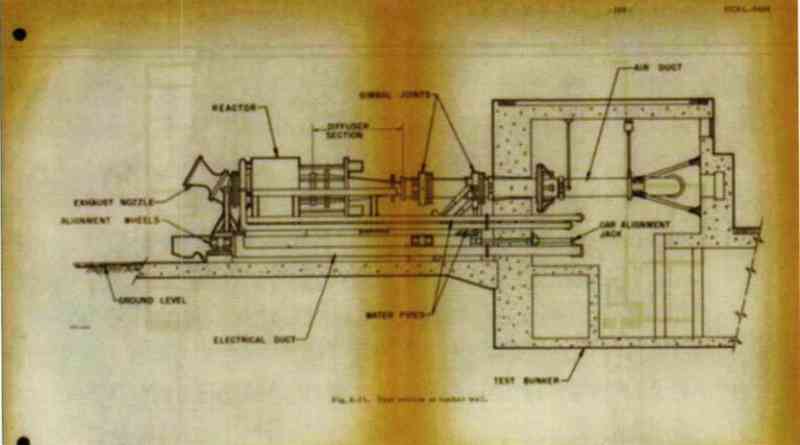

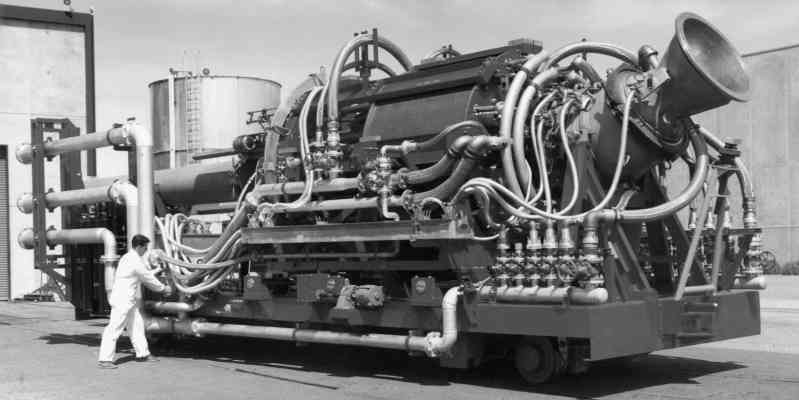

The actual test site of the "Pluto Project" reactor is in Area 20 of the National Test Site in the Nevada desert. A fully automatic railway transports the test engine to the test site. Scientists watch TV and receive data 3 kilometers away. The observation site can be completely closed, and dust removal equipment, 2 weeks of water and food are also prepared. In order to simulate the airflow blowing into the engine at 3 times the speed of sound, they use a 40-kilometer-long oil pipeline to store compressed air, borrow the giant compressor of the Navy Submarine Base in Groton, Connecticut, and use fuel to heat the air in four huge oil tanks to more than 700 degrees Celsius before blowing it into the reactor.

On May 14, 1961, the first nuclear-powered ramjet prototype Tory-IIA ran for 5 seconds. But this has proved its feasibility, because before the test, some people in the Nuclear Energy Commission were worried that the engine would directly catch fire and burn itself. Tory-IIB remained on the drawing board, but three years later, the larger Tory-IIC was transported to the test site, ran for 5 minutes, and successfully conducted a full thrust test. The engine generated 513 megawatts of power, equivalent to about 35,000 pounds of thrust-6,000 pounds more than the F-16’s Pratt & Whitney F100-PW-229 turbofan engine when it was burning at full power. The emission of radioactive gases was less than expected, which marked the success of the "Pluto Project".

Everyone in the project team excitedly talked about the perfect form of the project, Tory-III, which is expected to have enough power to accelerate the missile to Mach 4. In addition to the engine of the "Pluto Project", the design of the missile body of SLAM is also in progress. After the initial screening, the Air Force decided that North American Aviation, Vought and Convair would compete for the design. Convair’s body design is called "Sledgehammer", which is a nose air intake design. North American’s design is similar to Convair. However, the winner was Vought, which is a belly air intake configuration. Vought’s SLAM missile has six main wing surfaces, the front three are movable control surfaces, and the rear three are wings. After 1,600 hours of wind tunnel experiments at NASA, the circular air inlet with shock cone was replaced by a newly designed shovel-shaped air inlet. The new air inlet is more adaptable to various flight postures and has a better pressure recovery coefficient. In order to withstand the high temperature of more than 500 degrees Celsius during flight, the missile shell is made of nickel-based Rene41 alloy. In order to increase heat dissipation, the front missile shell is gold-plated, so it appears golden. The front of the missile is an equipment compartment. In order to protect the electronic equipment, a radiation shield is installed. The most important one is the terrain matching system navigation system. The inertial + starlight guidance system of the "Snake Shark" missile did not perform well in actual use. In May 1956, a "Snake Shark" D missile launched from Cape Caravinal was originally planned to return to Puerto Rico, but the missile ignored the return order and disappeared over the Caribbean Sea. It was not discovered until the 1980s in Maranhão State, Brazil.

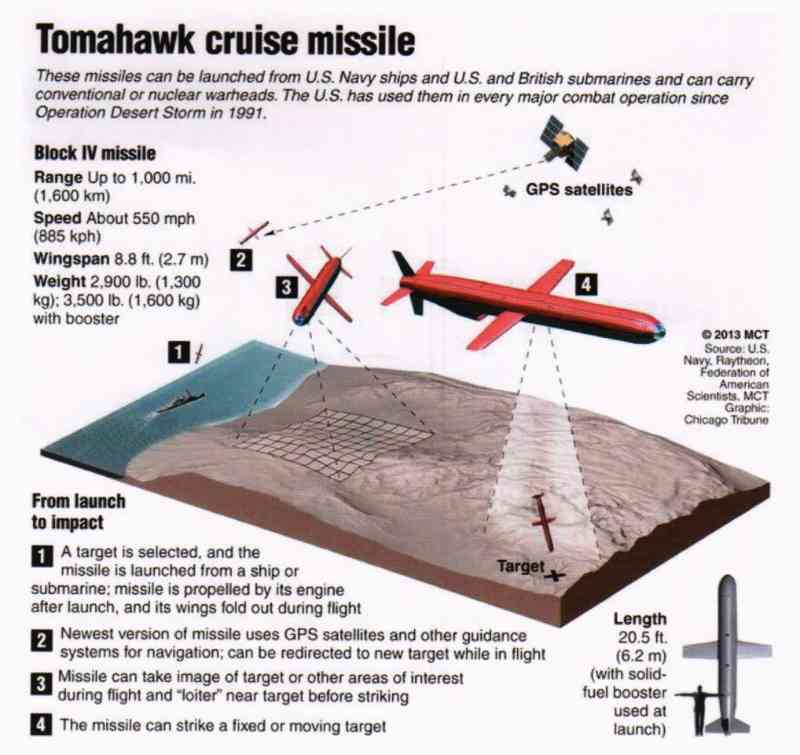

Considering the huge range of the SLAM missile, a more accurate navigation system must be used. Therefore, in addition to configuring a better inertial navigation system, the SLAM missile also developed the world’s first terrain matching navigation system FINGERPRINT. The US Air Force renamed it TERCOM and later used it on the "Tomahawk missile. TERCOM records the height data of the ups and downs of the terrain on the path in the seeker. During the flight of the missile, the radar rangefinder is used to compare the recorded data to know whether it is currently deviating from the route and where it is in the route. Due to this guidance mode, a very complex route can be set for the missile, so the missile can fly at a super-low altitude at subsonic speed along the undulating terrain to avoid the enemy’s search radar or greatly compress their reaction time.

The US Air Force plans to deploy SLAM on the coast and islands to minimize the impact of radioactive exhaust on its own territory.

When the United States enters the first level of combat readiness (DEFCON1), all SLAM missiles will be launched before the outbreak of a nuclear war. The missiles will take off by bundling booster rockets, and then start the nuclear reactor to rise to an altitude of 9 kilometers, and start circling in the predetermined sea area. At this altitude, it can fly 180,000 kilometers, which is equivalent to 4.5 laps around the earth. The fuel is enough to wait for the next command. Except for the fish under the flight area and some unlucky fishermen, no one will be shot. If the war is aborted by chance, the missiles will not be able to return, but will rush into the sea under control, sending the reactor and nuclear warheads to the deep sea.

If war breaks out, the SLAM missile accelerates to Mach 3 and rushes to the target, and before entering the Soviet radar range, it descends to an altitude of 300 meters. There are also data showing that under the control of the radar altimeter, the SLAM can fly at treetop height (15 meters). SLAM can carry 1 to 42 nuclear warheads. In fact, against most targets, multiple small-yield nuclear bombs are more effective than one large nuclear bomb, so SLAM generally carries 14 to 26 nuclear warheads. Each missile costs $50 million, equivalent to $600 million in 2022. The US military plans to equip 50 missiles, which can drop 1,300 warheads on the Soviet Union at a time. When SLAM drops a nuclear bomb over the target, it actually ejects the warhead like an ejection seat, and then the missile quickly leaves the explosion area and heads to the next target. When the SLAM missile flies, its exhaust will also continuously throw out uranium-containing radioactive dust, causing damage to Soviet territory. In fact, some people have suggested that after all the warheads are dropped, the missile should continue to fly over the Soviet Union to contaminate as much area as possible. If the Soviets shoot down the SLAM missile, the radioactive contamination will also be spread everywhere.

Obviously, this is a weapon that spreads disasters to the maximum extent. But it is precisely because of this that the US Congress and the Department of Defense eventually rejected the SLAM project on the grounds that it was "too provocative." First of all, the sound of this aircraft is so loud that the designers believe that the sonic boom it emits alone can kill any creature on the flight path. In addition, even without the sonic boom, the gamma rays and neutron radiation emitted by the engine without shielding measures will make the engine itself a weapon, but it also prevents the SLAM missile from flying over allies. In other words, if the missile is really to be equipped and launched, it can only be in places close to the Soviet border. However, this will also make it very easy to be destroyed by the other side, because how can the enemy allow such a terrible weapon to be deployed under its nose. In the Cold War environment where everyone was on edge, a weapon that created huge pollution when launched was a threat to everyone.

More importantly, during the development of the SLAM project, intercontinental ballistic missiles have matured. This is considered a more effective and reliable tool for delivering nuclear weapons. So on July 1, 1964, the "Pluto Project" was officially cancelled, and more than 300 experimenters held the "Last Supper". At the dinner, technical director Merkel presented souvenirs to everyone, including Pluto-branded mineral water. The Pluto project lasted for 7 years, with more than 600 participants and costing $260 million.

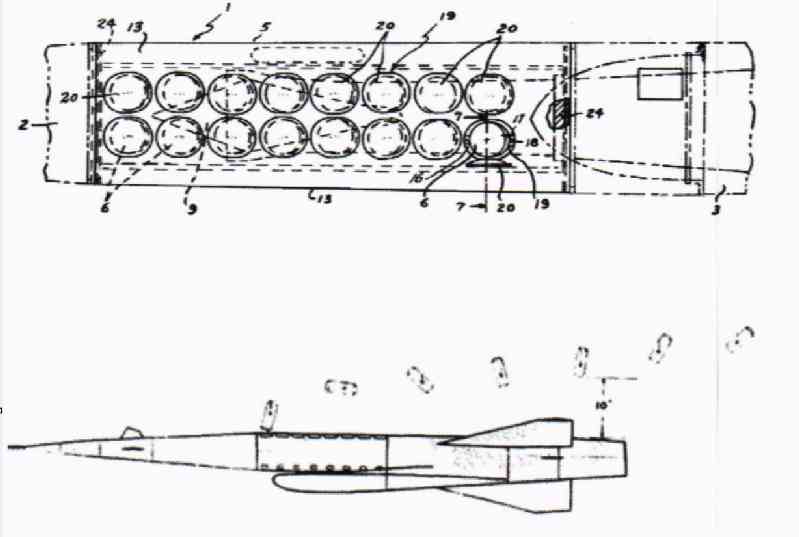

Almost at the same time as the "Pluto Project" was being promoted, the Soviet Union was also developing similar weapons. Starting in 1960, the Tupolev Design Bureau began to convert the Tu-123 unmanned reconnaissance aircraft into a nuclear-propelled cruise missile. The Tu-123 is a 25-meter-long, 28-ton behemoth that uses a Tumansky R-15 (the power of the MiG-25) turbojet engine. The nuclear-powered version of the Tu-123 has a similar body size and solid booster to the conventional-powered Tu-123 drone. The main difference is that the original R-15-300 turbojet engine and its fuel tank were replaced with a small nuclear reactor and turbojet engine developed by the Kuznetsov Design Bureau to give it almost unlimited endurance and range. The several cameras and reconnaissance equipment originally on the head of the drone were replaced by a thermonuclear warhead. However, for similar reasons to the "Pluto Project", the nuclear-powered version of the Tu-123 also failed to bear fruit and stopped development in 1964...

The "Swift"/"Skyfall" of the New Era

It is interesting that the ancient concept of nuclear-powered cruise missiles has regained favor after the Cold War atmosphere once again enveloped them. In the 2018 Russian State of the Union Address, Russia made a high-profile exposure of their "Swift" nuclear-powered cruise missile and announced that it would soon begin testing it on the Kamchatka Peninsula. This weapon is said to be able to reach more than Mach 5, not only with unlimited range, but also always working at hypersonic speed.

As for the reason why nuclear-powered cruise missiles regained favor after the end of the Cold War, it lies in a changed era of technological background: with the continuous rise of the United States’ strategic anti-missile capabilities, Russia’s original strategic nuclear deterrence system with intercontinental ballistic missiles as the core is facing the possibility of failure. It is also in this context that Russia has once again launched the research and development of nuclear-powered cruise missiles.

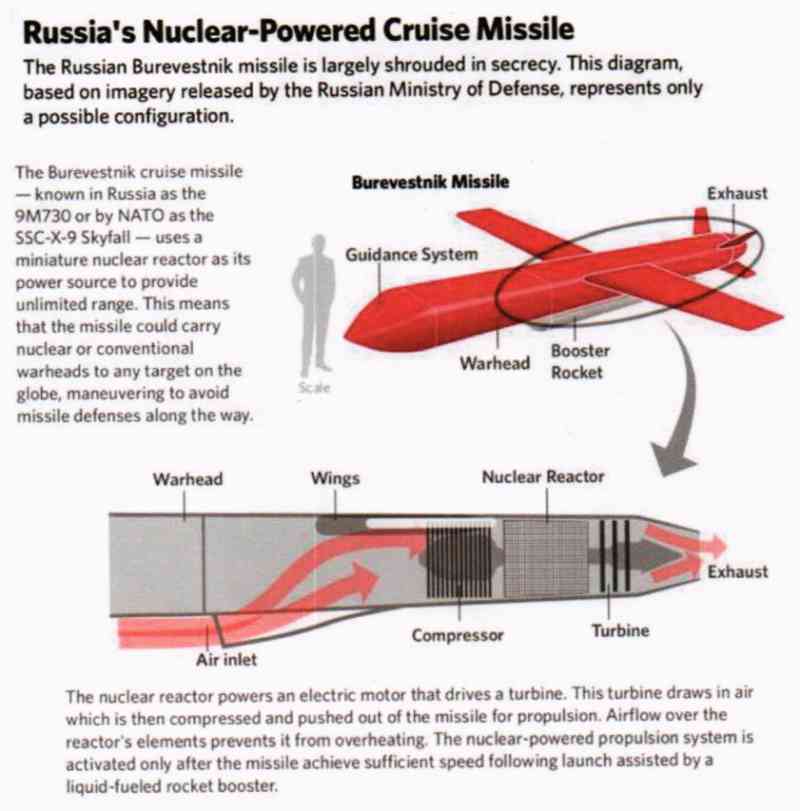

Russia restarted nuclear-powered cruise missiles, and there are two technical targets. First, in principle, the use of nuclear reactors will give cruise missiles unlimited range, enabling them to perform complex evasive maneuvers outside the detection range of US missile defense radars and interceptors. Second, nuclear reactors can provide continuous high propulsion power, which fundamentally solves the power problem of hypersonic flight and further enhances the penetration of missiles. It is generally believed that the Russian nuclear-powered cruise missile, known as the "Swift", is the Russian military standard model 9M730, NATO code name SSC-X-9, "Skyfall"

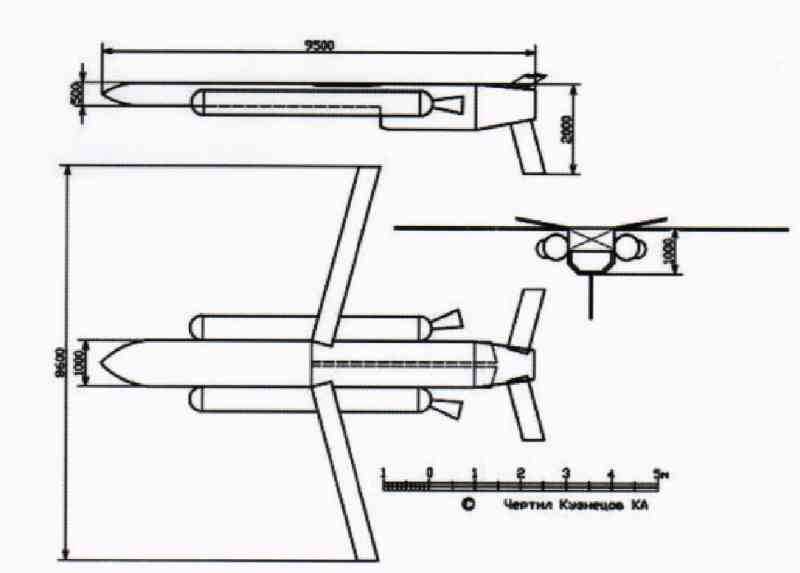

According to information released by the Russian Ministry of Defense, the size of this missile is similar to that of the KH-10 cruise missile, but the power equipment is a small nuclear-powered engine, and the range is also several orders of magnitude higher than that of the KH-10. When launching, the solid-fuel rocket is first launched to launch the nuclear missile. At the same time as the solid rocket engine falls off, the nuclear-powered engine is started and enters the cruise state. According to the information, the missile is 12 meters long when launched, but 9 meters in the cruise state, so the solid booster rocket may be 3 meters.

Russian military expert Anton Lavrov pointed out in an article written in Izvestia that the design of "Swift" is mainly based on nuclear-powered ramjet engines. Unlike the nuclear propulsion system of spacecraft, it will produce radioactive exhaust gas throughout its operation. In other words, this is a "nuclear-powered ramjet engine" that uses a heat exchanger to heat the air with high-temperature heat and then ejects it. In fact, the direction of use of nuclear-powered engines in outer space is interstellar travel. The medium is mainly liquid hydrogen. The principle is that nuclear power heats liquid hydrogen at high temperature and expands it and then ejects it to drive the rocket to fly. Its specific impulse can reach 800~1000, which is about twice the most advanced chemical rocket in modern times. There is a big difference between the engines in the atmosphere and those in space. The working fluid cannot be obtained in space, and only the rocket itself can carry it, but it is not the case in the atmosphere, because the air we breathe is the medium. Therefore, there are two modes of nuclear-powered engines in the atmosphere, one is open and the other is closed. The open structure is simple and violent, that is, air is sucked in from the atmosphere, flows through the hot core, expands, and is discharged to the rear. This is the power source of nuclear-powered unmanned aerial vehicles. The nuclear-powered ramjet engine of the "Swift" belongs to this category, and is actually no different from the Tory engine of the Pluto Project.

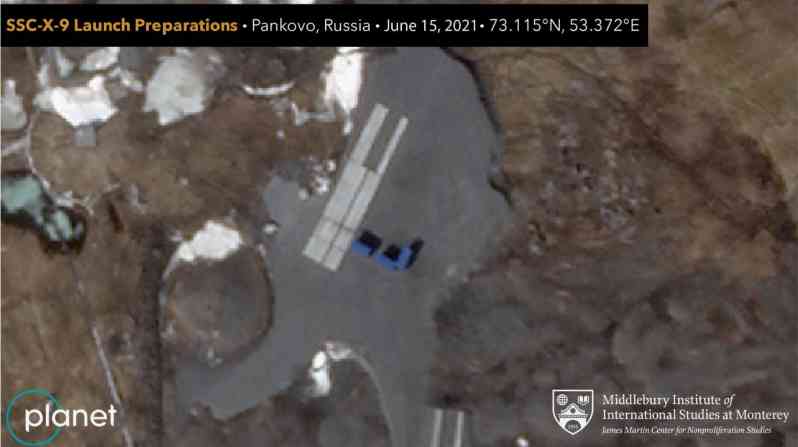

Of course, the principle of the nuclear-powered ramjet engine is very simple. The air flows through the nuclear reactor and is heated and ejected from the rear. But the problem is that the air will not be so obedient without reason, so there must be a relevant specific power structure to achieve it. It is generally believed that there is a multi-stage turbine compression in front of the "Swift" nuclear-powered cruise missile inlet, a nuclear-powered reactor in the middle that heats the air, and a power turbine in the rear. When the high-temperature air expands and ejects, it drives the turbine, driving the multi-stage turbine in front to operate, and finally the exhaust gas is discharged from the rear. This structure is not much different from the turbojet engine. The only difference is that the turbojet engine has a combustion chamber in the middle, while the nuclear-powered engine has a nuclear reactor in the middle. Russia conducted at least one test launch of a nuclear-powered cruise missile at the same location near the Arctic Circle in November 2017, and foreign media reported that Russia conducted several more tests in the following months, but none of them were considered successful. However, on August 20, 2021, Russia conducted another related test, which may have achieved relatively satisfactory results.

Experts from the Center for Nonproliferation Studies at the Middlebury Institute of International Studies in the United States said at the time that some satellite images taken by the commercial satellite imagery company Capella Space on August 16, 2022 provided "clear signs that Russia is preparing to test nuclear-powered cruise missiles at a known launch site near the Arctic Circle." Subsequently, experts from the Center for Nonproliferation Studies at the Middlebury Institute of International Studies believed that the "Swift" nuclear-powered cruise missile test conducted by Russia was basically successful. But at the same time, they also expressed strong concerns about Russia’s repeated tests of nuclear-powered cruise missiles in the atmosphere, that is, there are still many questions about whether this system can operate successfully, not to mention the threats that testing this system may cause to the environment and human health."

In fact, after the news of Russia’s nuclear-powered cruise missiles was released, the radioactive impact during its flight has always been one of the key issues that have always received attention. According to Western media reports, in January, February and October 2017, Nordic countries all found abnormal increases in radiation. Experts believe that this may be due to Russia’s ground tests of nuclear engines or nuclear power engines. The impact of the test flight of the cruise missile. Although this statement has not been confirmed by Russia, it also shows the outside world’s concerns about its safety.

In the public’s imagination, open nuclear engines working in the atmosphere are actually It is too scary, because the air flows directly through the core, carrying a large amount of radioactive materials and directly discharged into the atmosphere, leaving a road of death. After water vapor circulation or settling on the ground, radioactive pollution will spread all over the world. But this problem cannot be taken for granted, but requires specific analysis. When a nuclear-powered cruise missile is flying in the air, the dose formed by the reactor needs to consider three factors.

1. The direct radiation dose caused by the leakage of neutrons and photons in the reactor core to the surrounding environment; the neutrons and photons leaked from the reactor form a dose field in the air. If someone is in the dose field, it will form a radioactive Hazards. Due to the attenuation of radiation with distance in space and the absorption and scattering of radiation by air, the neutron and photon dose rates decrease with increasing distance from the reactor.

2. During the flight, the air used for core cooling and the surrounding air are activated, and the activation products produced are radioactive; after the air is irradiated by the reactor neutrons, some nuclides will be activated to generate radioactive nuclides. Air activation can be analyzed in two parts: one is the air passing through the core, which is irradiated by a higher neutron fluence rate, but the total amount of activation is small; the other is the surrounding air outside the core, which has a low neutron fluence rate outside the core, but the total amount of air activated by radiation is large.

3. Diffusion and leakage of fission products in the reactor. Due to the restrictions on the weight and volume of the reactor by nuclear-powered missile engines, it is more likely to adopt a design form that directly cools the reactor by inhaling air. If the fuel is damaged during the operation of the reactor, radioactive fission products may leak and enter the atmosphere through the cooling air, forming a relatively serious radioactive pollution. Due to the particularity of the reactor directly cooled by air, there is a lack of effective data on its fuel design and damage rate, making it difficult to conduct a more accurate analysis. Therefore, only the first two sources of radioactivity are temporarily considered in the analysis, namely the radioactivity directly radiated by reactor neutrons and photons and the radioactivity of air-activated products. As for the specific technical details of the "Swift", the Russian technical data is relatively small, and the analysis is only based on the test data of the ground test of the US nuclear-powered missile TORYI-C. In 1957, the United States began to implement the "Pluto Project" to develop the low-altitude supersonic cruise missile "SLAM". The United States has successively manufactured two nuclear ramjet engine ground test prototypes "TORYⅡ-A" and "TORYⅡ-C" in the "Pluto Project". Among them, the test prototype "TORYⅡ-C" has greater power, and its main design parameters are very close to the reactor that can be actually used on SLAM missiles. On May 12, 1964 and May 20, the United States conducted two surface tests of "TORYI-C" before and after the Nevada Test Site. During the test, the prototype worked continuously for 300s at nearly full power, with a maximum thrust of 156kN.

The radioactivity measurement during the test is divided into two parts: one part is the close-range radiation measurement and analysis conducted by the test personnel in the test site during the test; the other part is off-site monitoring. The U.S. Atomic Energy Commission (AEC) and the U.S. Public Health Service (PHS) have established a special off-site radioactivity safety team to monitor the radioactivity within a radius of 300 kilometers around the Nevada Test Site. It is worth noting that, due to the short operation time of "TORYI-A" and "TORYⅡ-C" and the fact that ceramic fuel has been tested in the American Nuclear Powered Aircraft (ANP) project, the air flowing through the reactor core was directly discharged into the atmosphere during the ground tests of "TORYⅡ-A" and "TORYⅡ-C" in the United States, which may be very close to the situation of "Swift".

TORYI-C has a design target power of 500 MW. The actual power of the two tests on May 12 and 20, 1964 was 297 MW (60% design power) and 461 MW (close to full power) respectively. During the test, the operation time at 60% design power was about 250 seconds, and the operation time close to full power was about 300 seconds. While the reactor was operating, the test team measured the radioactivity around the reactor, using various types of detectors to measure the radioactivity from the outer wall of the reactor to a photographic shelter at a distance of 600 feet (about 183 meters). The neutron fluence rate and gamma dose rate leaked from the reactor varied with space.

The off-site radioactive safety team monitored the off-site radioactivity during the test by various means, including: 10 sets of ground monitors to monitor the radioactive dose formed by the reactor exhaust gas during the test; remote dose recorders, arranged at 16 locations around the test site; aircraft tracking in the air to monitor the reactor radioactive gas emissions during the test from the air; film badge dosimeters, 65 film badge dose points were arranged outside the test site, and film badge dosimeters were distributed to 166 residents.

PHS also conducted remote air, milk and water sample measurement and analysis outside the test site. In the 60% power test, only one ground monitor detected a dose of 0.2 microsievert/hour. No radioactivity was detected in plant sampling measurements about 4 hours later. When operating at full power, the ground monitor at a distance of 46 kilometers detected a dose of 0.5 microsieverts/hour, and the ground monitor at a distance of 52 kilometers detected a dose of less than 0.5 microsieverts/hour. The remote dose recorder did not detect any radioactive data exceeding the background. The film badge dosimeter also did not measure the dose radiation related to the TORY test. A very small amount of newly produced fission products was detected in the air sampling, and only one mutandis 133I (half-life 20.8h) was detected. From the radioactivity measurement results of TORYI-C, it can be seen that the radiation dose rate at close range around the nuclear-powered engine for cruise missiles is relatively large. At a distance of 20 meters, when the reactor was operating at a power of 461 megawatts, the photon dose rate alone reached 1.4 sieverts per second. However, the radiation dose rate decays rapidly with distance. At a distance of 200 meters, the dose rate decays by more than 2 orders of magnitude compared to 20 meters.

In addition, the short-term operation has little impact on the environment outside the test site. The design of the reactor fuel in the TORYII-C test adopts the form of UO2+BeO dispersion, and no containment structure such as cladding is set for the fuel. In addition, during the test, the air flowing through the core is directly discharged into the atmosphere. Under such test conditions, monitoring data show that due to the restrictions of the missile on the weight and volume of the reactor, the shielding is relatively poor, and the radiation dose rate at close range of the power engine is very high; but after a short period of operation, the impact on the environment outside the test site can be ignored... If TORYⅡ-C is used to analogize "Swift", without considering the leakage of fuel fission products, the effective dose formed by the missile flying from the air once, within a range of more than 80 meters in the normal direction of its flight trajectory, will be lower than the annual dose limit for nuclear power plant workers in the GB18871-2002 standard. Of course, no matter how reliable a nuclear-powered engine is, its safety cannot reach 100%, so the possibility of its crash still exists, and once it crashes, nuclear contamination is inevitable.

To reduce the probability of this happening, cruise missile reactors should try to use a fuel design with strong tolerance to reduce the probability of radioactive product release. From this perspective, the technical feasibility of "Swift"/"Skyfall" should be able to reach a fairly high level. In fact, the reason why early nuclear-powered cruise missiles such as "Pluto Project"/SLAM were cancelled was that the problem of radioactive contamination during flight was largely just an excuse. The key to the problem is that intercontinental ballistic missiles are more cost-effective than nuclear-powered cruise missiles. However, today when anti-intercontinental ballistic missile technology is close to maturity, the advantage of nuclear-powered cruise missiles in being able to perform long-range complex evasive maneuvers at hypersonic speeds is clearly highlighted.

Conclusion

The technical ideals of high-performance aviation vehicles for power systems are mainly two points: high thrust-to-weight ratio and long flight time. Both performances require high-density energy fuel as a power source. At present, aviation fuel used by aircraft is the energy type with the highest energy density among conventional fossil energy sources except nuclear energy. However, even so, aircraft often need to carry several tons, dozens of tons, or even hundreds of tons of aviation fuel. In order to increase the flight distance, some aircraft need to refuel in the air. These have many adverse effects on the technical performance of aircraft. As the energy type with the highest energy density, nuclear energy naturally becomes an extremely attractive technical path to obtain high-performance aviation power. It is also for this reason that, as a relatively old concept, nuclear-powered cruise missiles are still fascinating today because they have better penetration performance than intercontinental ballistic missiles. Human obsession with unlimited range will always exist.