As the US Navy gradually shifts to a distributed maritime combat mode, its supply chain is also facing various new challenges. In the past few decades, the US military has always believed that it can provide sufficient supplies for troops carrying out rapid operations without worrying about being hit. However, as potential adversaries gradually master long-range weapon systems that can attack transportation hubs and assembly points at any time, this complacent attitude is becoming increasingly untenable. In addition, as the US joint forces increasingly focus on decentralization and flexibility, this has also brought new challenges to the supply of highly mobile forces. This shift requires supply chains to be more flexible, efficient, and adaptable to cope with the complexity and uncertainty of distributed operations. However, the current US Navy’s logistics supply chain is stretched to its limits in dealing with these challenges.

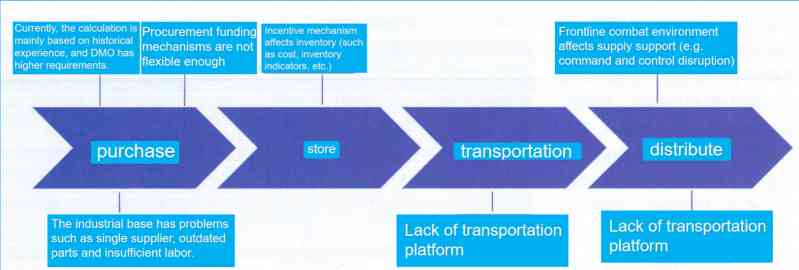

The military supply chain is a complex chain that starts at the place where the product is produced and ends at the delivery of goods to combat troops. As long as there is a flaw in one of the links, the entire supply chain will face the risk of paralysis. For example, although the global fuel supply is sufficient, if it cannot be delivered to combat troops in a timely and effective manner, it will expose the shortcomings of the logistics supply chain in terms of maintenance capabilities. At the same time, in some emergency situations, the problem is not necessarily in the delivery link, but the product production end cannot meet the needs of the battle.

In a complex and changing environment, operational forces need to rely on a variety of maintenance strategies. The clever use of pre-deployment strategies can effectively reduce the amount of materials that need to be transported over long distances, thereby improving overall operational efficiency. Despite this, a large amount of materials still need to be replenished through transportation.

These challenges faced by the logistics supply chain are not limited to specific categories of materials, but cover all types of materials. Although some materials (such as fuel) are mainly related to distribution, ammunition and spare parts span various supply chain areas. Like fuel, they must also be distributed to dispersed forces. The difference is that the global supply of ammunition and spare parts is not sufficient, and most of them need to be produced in industrial facilities in the United States. In view of this situation, we can focus on the supply of ammunition and spare parts, and deeply analyze the problems they bring to the supply chain, which is of great value to studying the problems existing in the US Navy supply chain.

The current situation of ammunition supply chain

In the US Navy supply chain, ammunition plays a very unique role, and the way ammunition is used is completely different from other supply categories. In peacetime, ammunition is mainly used for training, and the consumption of advanced weapons is relatively small, while in wartime, ammunition consumption will rise sharply, possibly reaching hundreds or even thousands of pieces. According to Rand Corporation’s calculations, in the Western Pacific combat scenario, during a 65-day conflict, 20 US Navy ships (roughly equivalent to two aircraft carrier strike groups) successively engaged 80 Chinese Navy ships, requiring a total of about 800 Tomahawk missiles and 1,200 long-range anti-ship missiles (LRASMs), half of which (400 Tomahawks and 600 LRASMs) will be exhausted within the first 15 days of the conflict. However, according to public information from the US Department of Defense, as of fiscal year 2021, the US Navy has only 147 LRASMs in its inventory. Although it plans to purchase another 162 in fiscal years 2022-2025, its inventory will only reach 309 by then, which is far lower than the 1,200 expected in the Western Pacific combat scenario.

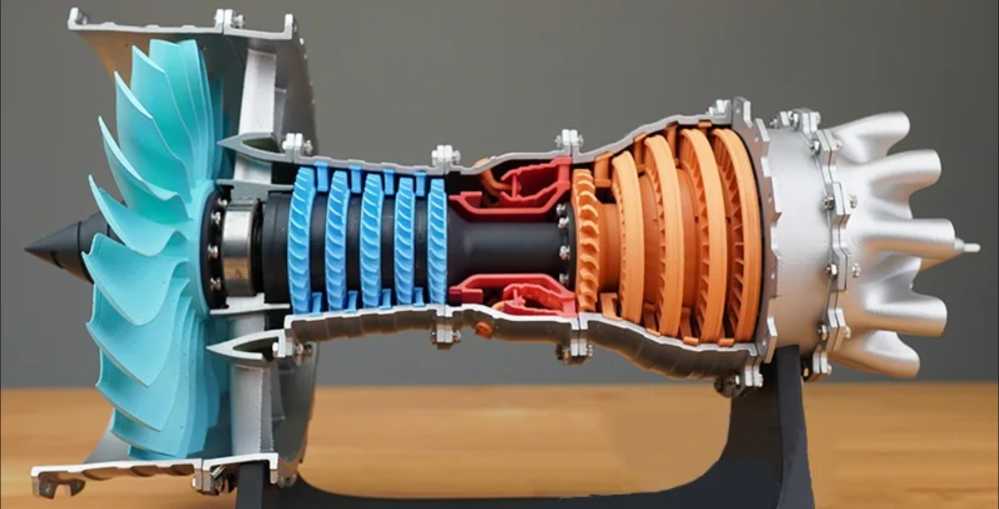

It is worth noting that LRASM and the Extended Range Joint Air-to-Surface Standoff Missile (JASSM-ER) are produced on the same production line and use common tools and production processes. The production line is located at Lockheed Martin’s missile and fire control plant in Troy, Alabama. The U.S. Navy and Air Force jointly purchased LRASM through an Air Force contract, which is consistent with the Air Force’s contract for JASSM-ER. In addition, the turbofan engines of LRASM, JASSM-ER and "Tomahawk" are all supplied by Williams International.

It is reported that the US Air Force plans to purchase 410 LRASMs and 7,200 JASSM-ERs by 2025. However, so far, only 4,444 JASSM-ERs have been received, and the remaining 2,756 have not yet been delivered. It can be inferred that by the end of 2025, the US Air Force will purchase a total of 3,166 LRASMs and JASSM-ERs from this production line. Such a large purchase volume will inevitably become an important issue that production units face when delivering ammunition to the US military. Important limiting factors. If a military conflict breaks out during this period, and the demand for both types of ammunition surges at the same time, it may cause the second-tier (and below) suppliers to face a choice, and they will have to give priority to providing components for one of the ammunition and temporarily postpone the supply of the other. In addition, if the US Navy and Air Force need to be resupplied at the same time, it is entirely possible that one of the services will need to be resupplied first.

In addition, according to the established plan, the US Navy is steadily advancing the comprehensive upgrade of the current "Tomahawk" Block IV cruise missiles, aiming to upgrade all approximately 3,992 missiles to the more advanced Block V. There are two versions of the Tomahawk Block V. Block Va is called MST, equipped with a multi-mode seeker, capable of accurately striking mobile targets at sea and possessing strong anti-ship capabilities, while Block Vb is equipped with a joint multi-effect warhead system (JMEWS) that can strike various land targets. Among them, MST will not achieve initial operational capability until 2024. If the current budget remains unchanged, it is expected that by 2025, the US Navy’s MST inventory may be only 116, a number far from the estimated 800 required in the Western Pacific combat scenario.

It can be seen that if the US Navy wants to increase its ammunition inventory throughout the supply chain, it will face the problem of insufficient production unit capacity and supplier supply capacity. This will make it difficult for the US Navy to obtain the expected amount of ammunition in major combat operations, especially distributed operations at sea, thus affecting combat effectiveness.

Response strategies for the ammunition supply chain

In order to solve the problems in the ammunition supply chain, the U.S. Navy needs to design corresponding response strategies according to its planning period, namely short-term response strategies (0-3 years), medium-term development strategies (2-7 years) and long-term design strategies (5-15 years).

Short-term response strategies Short-term response strategies mainly include reallocating inventory, expanding industrial capacity and increasing production shifts. This strategy is to produce quickly and quickly meet the surge in demand for ammunition, but its long-term applicability and sustainability are limited. Reallocating inventory is simply transferring ammunition from one place to another to meet current demand changes. The main advantage of this strategy is that it can increase the inventory of a certain location in the fastest, most economical and easiest way, and its main expenses are concentrated in transportation and logistics. However, this strategy also has risks in its implementation. When reallocating inventory within a theater or from another combatant command, the supply at the origin may be exhausted, making it difficult for the origin to meet the response needs in the event of a conflict. Therefore, the commander of the origin may oppose this strategy. In addition, this strategy is highly dependent on the adequacy of local stockpiles and can only be used as a short-term solution. It may be difficult to meet the full demand in an actual conflict scenario.

Since logistics and transportation are core elements of this strategy, insufficient infrastructure may be a major obstacle to this strategy, and transportation capacity cannot be fully guaranteed in conflict situations. In addition, the United States must comply with local laws and regulations when transporting supplies overseas. In order to minimize the risk to critical civilian infrastructure such as roads, bridges, tunnels and ports, only specific ports and routes may be allowed to be used to transport ammunition and ordnance; the amount of explosives transported at a specific time may also be limited. These factors not only limit the choice of loading and unloading ports, but also limit the ability to transport ammunition within another country, which may extend the time required to deliver ammunition.

Unlike reallocating stocks, the strategy of temporarily expanding production capacity aims to increase the supply of ammunition without transferring the risk of shortages to other locations. Its key costs include the procurement of new production facilities, equipment and tools, as well as the expenses incurred in producing ammunition. In addition, the purpose of temporarily expanding production capacity is to meet the surge in demand, so it is likely to be idle or maintain low-level production during normal supply periods, which requires retaining employees to meet the capacity when demand surges, or to recruit them temporarily and quickly. This strategy requires expanding most links in the supply chain, including upstream suppliers. If you choose to expand production capacity at the end of the supply chain, such as the integration and assembly stage of ammunition, the downstream part will be highly dependent on other stakeholders in the supply chain. If the capacity of a link in the supply chain is limited, which in turn affects the ability of the entire supply chain to increase production and meet demand, then this strategy may not be able to meet demand with existing resources alone, and additional investment is required to support it.

When adopting the strategy of increasing production shifts, under the premise that the production facilities remain unchanged, the capacity can be expanded by increasing the labor force. The supply chain will increase the number of employees hired on the basis of the existing labor force to operate the production line. This strategy can respond to potential surges in demand relatively quickly, but it depends on the combined effect of multiple factors. When recruiting personnel, a series of onboarding procedures are usually required, including obtaining security clearances and receiving professional training, which may prolong their time on the job. In addition, this strategy is also based on a sufficiently loose labor market to ensure that suppliers can quickly recruit experienced and capable employees. However, whether the labor market is abundant or short, finding the right employees based on recruitment requirements is a challenge. Similar to expanding production capacity, this strategy will likely need to be applied broadly throughout the supply chain. This is because certain parts of the supply chain may be highly dependent on contact labor or other key factors, and if one part cannot meet the needs of another part, the overall output will continue to be affected.

The short-term response strategy is based on the basic assumption that the required materials are sufficient and available. This means that when the personnel are fully staffed, the production materials can be obtained quickly to ensure that the installed capacity can meet the demand. However, in some cases, there is a competing demand for a specific common component between different munitions, which will cause any munition to reduce the amount of the same component obtained from another supply chain when meeting the production demand. When there is competition for components and materials, this strategy will appear to be a loss of one thing while another.

Medium-term development strategy

Medium-term development strategies include increasing inventory and building new factories. Compared with short-term mitigation strategies, medium-term development strategies are less restrictive and have more time to reduce risks. Although they may not solve the current combat readiness problem, they can promote changes in the supply chain in a more lasting way.

Increase inventory strategies require procurement preparations in advance of the demand surge, and their timetable may vary depending on the expected demand surge and the capacity of the supply chain. Procurement plans can be set to be completed over a period of several years to relieve the production pressure on the supply chain. However, if there is an unexpected demand surge during the procurement process, it will not be able to meet the requirements. If procurement is completed in a relatively short period of time, the supply chain will be under great pressure to meet procurement and inventory requirements. The strategy of increasing inventory is also based on the assumption that the existing supply chain has the ability to meet the needs of increased production and inventory growth, or that the supply chain can be expanded to accommodate these needs. In either case, this procurement activity requires a large upfront capital investment. The main problem faced in implementing this strategy is the chain reaction caused by raising funds for increasing specific ammunition, because expanding the inventory size requires a large amount of capital investment, and this is a fixed expense that cannot be changed. At the same time, once the decision is made to invest in a certain type or group of ammunition, these funds will most likely need to be allocated from other options or ammunition, thereby limiting the ability to respond to surges in demand for other ammunition or ordnance. However, in reality, surges in demand are often difficult to predict, and in most cases they cannot be predicted at all. Therefore, while increasing inventory can improve the ability to respond to surges in demand, it also means that a large amount of funds are "fixed" in specific ammunition inventories, and there is no flexibility to respond to different situations that may arise.

Building new factories can expand production lines to produce more ammunition. This strategy requires building new facilities, purchasing equipment and tools, and adding production staff. These additional facilities and capacity can be used to supplement existing capacity to increase inventory. In peacetime, these facilities can be kept running below maximum capacity and then increased when demand surges. A major advantage of this strategy, and also its greatest weakness, is the "permanence" of its investment. Building new facilities requires a large upfront capital expenditure, and if the facilities are running below maximum capacity, they may be shut down and kept at a minimum level of staff to achieve inefficient operation, which will increase costs in the long run. When demand surges, in order to increase production, the number of employees must be increased, the mothballed equipment must be activated, and more materials must be purchased, which will lead to a significant increase in costs. On the other hand, if facilities are kept running at normal capacity during periods of flat demand, additional costs will be incurred for those facilities and staff. In addition, depending on the facilities and nature of the munitions produced, this investment may reduce flexibility in responding to different munitions needs. If the production facilities required for a certain munition are unique, their ability to meet surge demand will be limited, and relying on only a specific type of munition will not be able to meet all needs due to the diversity of demand. If the facilities and production staff can handle surges in demand for multiple munitions, then the strategy can better respond to more diverse demands. Therefore, to implement this strategy, production lines that produce common components for multiple munitions should be established or expanded, and the shared production line for LRASM and JASSM-ER is a good example of this strategy.

Long-term design strategy

Long-term design strategy refers to the strategy of changing the overall nature of ammunition and then changing the supply chain. With long-term time conditions, it is possible to flexibly formulate force design and record plans (Program oRecord). These strategies include introducing and expanding modular design throughout the supply chain and adopting additive manufacturing technology.

Modular design is the process of breaking down a larger system (such as ammunition) into smaller, independent systems (modules) that can be connected and exchanged in various combinations to produce different ammunition products using a shared platform. With a modular system, more common parts in different systems can be reallocated to quickly meet surging demand, but the premise is that these parts are interchangeable in different systems and there is sufficient inventory. Modular design not only allows individual components within the platform to be exchanged and maintained independently of other parts of the system, but also makes upgrading the entire system easier and more efficient.

Maintaining and upgrading the system through modular design can provide personnel who originally focused on maintenance work with the opportunity to transfer to the production line, thereby increasing available human resources and better responding to surging demand. In addition, modular systems can reduce development costs due to their universal design, that is, instead of redesigning dedicated components for each new system, it is better to use previously designed components. Another aspect of cost savings may come from increased competition in the sub-component market, in which case potential suppliers will bid to provide modules for shared platforms instead of bidding for the entire platform. This practice not only helps to reduce costs, but also reduces the risks associated with relying on a single supplier in the ammunition supply chain. The modular design of the Joint Direct Attack Munition (JDAM) was praised for its ability to be quickly assembled on the battlefield during Operation Inherent Resolve, the U.S. military’s campaign against the Islamic State in Iraq and Syria in 2014. The modular system in the munition allows the munition to be quickly modified on the battlefield, such as by adding or removing a laser sensor kit on the JDAM, to meet different conflicts or mission requirements.

The long-term investment required to transition to a modular system may be difficult to fund. In addition, original equipment manufacturers may be hesitant to invest in developing new capabilities. Modular systems and the overall modular capabilities required will significantly change common ammunition supply chain practices and change the face of the supply chain, which is a slow process and will increase procurement time in defense procurement procedures. To properly develop a shared platform to which subcomponents can be added, it must be designed to meet the needs of a variety of missions. Each time a new modular component is proposed, the platform needs to be certified in various configurations. Therefore, modular munitions are unlikely to shorten the time required for testing and evaluation certification.

Additive manufacturing, also known as "3D printing", opens up new opportunities for diversified production methods throughout the ammunition supply chain. This manufacturing method is achieved by "printing" materials layer by layer. The significant advantage of this process is the ability to quickly develop and modify parts in the supply chain. Compared with traditional machining methods, the layer-by-layer printing characteristics also facilitate the manufacture of special structural parts. Parts that previously required complex welding or assembly with consumables (such as nuts and bolts) can now be integrated into a single component, which not only reduces weight, reduces the number of parts, but also reduces material costs. Take CFM International’s LEAP engine as an example. It has used metal 3D printing technology to produce fuel nozzles, replacing parts that were previously composed of 20 separate parts.

In addition, the characteristics of additive manufacturing printers and layered production methods allow different parts to be manufactured using the same equipment, that is, they can quickly switch between different product lines, thus forming flexible production capabilities. In addition, the conversion requirements required to adjust equipment to produce new parts using different materials are relatively low. Instead of re-equipping the entire production line, a few printers can be quickly reconfigured and the appropriate materials and component design drawings can be used to produce the required number of spare parts. However, the risks of applying additive manufacturing vary in specific supply chains and ammunition production processes. The application of additive manufacturing in the supply chain may be limited by location and method, and there are currently systems that cannot be manufactured using additive manufacturing processes. For example, when using different materials to manufacture parts, how to effectively connect these parts together is a problem faced by current additive manufacturing technology. The integration and assembly of ammunition may always require contact labor at some point in the supply chain. Finally, it must be pointed out that the process of persuading original equipment manufacturers to adopt additive manufacturing technology will also be slow, and if one printer is responsible for producing different components, it may hinder its ability to meet the production needs of multiple components or systems at the same time. To avoid this problem, more printers need to be purchased and more money needs to be spent.

The current situation of aviation parts supply chain

In recent years, the US Navy Air Force has faced the challenge of declining annual mission qualification rates for aircraft. The study found that there are many problems in supply and maintenance, such as unexpected replacement of maintenance parts due to aircraft aging, extended service life, warehouse delays, lack of trained maintenance personnel, reduced manufacturing sources, obsolete parts, and parts shortages.

To this end, the U.S. Navy has taken a number of initiatives to address these problems. The relevant measures not only cover planning performance (P2P), Navy Sustainment System-Supply (NSS-S), integrated supply chain management (ISCM) and Navy performance improvement education resources, but are also collaborative and aim to integrate all stakeholders in the supply chain to eliminate long-standing barriers in the system. The core is to use data-driven methods (i.e., starting from the initial data or observations, finding and establishing relationships between internal features to discover theorems or laws) to achieve quantifiable results as the ultimate goal. It has been proven that these initiatives have effectively restored the recent combat readiness of the U.S. Navy Aviation.

In the process of determining and procuring spare parts requirements for the Navy Aviation Force, the Defense Logistics Agency and industrial enterprises, as key stakeholders, play an indispensable role and provide important external support. The Defense Logistics Agency is the combat logistics support agency for the U.S. military services, combatant commands, and, when necessary, other government agencies and allies. The Defense Logistics Agency is responsible for managing the "end-to-end global defense supply chain from raw materials to end-user configuration." The main criterion for measuring its performance is how to maximize the material availability rate.

Material availability rates are generally low due to the poor predictability of repair parts, small order quantities, and military-only use. In order to achieve a high material availability rate for repair parts, the Defense Logistics Agency system will prioritize the storage of parts with lower prices and predictable demand, and minimize excess inventory. For expensive parts that are not often in demand, lower material availability rates are allowed. Although material availability rates are a valuable metric from a business perspective, focusing solely on improving material availability rates is not enough to fully reflect the degree to which the needs of the troops are met, especially for critical parts. Additionally, this may cause the DLA to be too focused on meeting existing steady-state demand and neglect to optimize for future demand.

Recognizing this, the DLA has actively supported the Service Requirements Readiness Summit since 2018 to gain insight into the expected demand for Class IX materiel (the Department of Defense defines Class IX as "repair parts and assemblies, including kits, assemblies, and subassemblies required for all equipment maintenance support") in the maritime and aviation sectors for future operations. The summit provides a platform for the services to communicate their priorities and expected needs to the DLA, and without service-level feedback, the DLA system will default to historical data as a reference. Although the summit is not formally incorporated into the forecast model, it provides valuable information to the DLA system to help manually adjust the forecast level to make it more accurate and balanced with fiscal constraints.

Industrial enterprise optimization aims to maximize profits and revenue. Therefore, business decisions should be aligned with these goals. For some systems, such as the F-35, defense contractors assume some of the management of maintenance parts through performance-based logistics contracts. The primary goal of these contracts is to incentivize contractors to achieve specific system availability levels, rather than simply focusing on transaction numbers. This gives them an incentive to improve system reliability to achieve economic benefits using fewer spare and repair parts. However, the organizational infrastructure and culture of most contractors are optimized for transactional, profit-maximizing execution, especially if the military portion of the business is only a small part of the overall business, which is the case for many U.S. aerospace contractors. In the case of the F-35, the prime contractor is responsible for managing the spare parts supply chain: and is accountable for availability metrics, yet a recent review of the F-35 supply chain found that the F-35 had many problems meeting performance requirements due to spare parts shortages and maintenance backlogs.

According to the concept of distributed maritime operations, the aircraft of the US Navy will fly longer, and the demand for aircraft capable of performing missions will become more urgent. As the flight time increases, the accumulation of flight hours will be faster, so the need for phased maintenance will be more frequent. When fighting with competitors of similar strength, it is likely to cause huge combat damage, which requires the replacement of most parts of the aircraft, such as wings. In addition, the way aircraft fly in wartime is different from that in peacetime. During the "Desert Storm" operation in the Gulf War, due to the fact that the actual aircraft dispatch rate far exceeded the plan and the significant increase in flight time, some subsystems were under great pressure, which caused the failure rate of all aircraft of the US Air Force to increase by 2 times. Similarly, during the operation, the damage rate of each model was different. For example, the damage rate of the F-15C increased immediately after deployment, which is likely because the F-15C used its various systems more than usual during the combat air patrol (CAP) mission. For the F-16C: In the early stage of deployment, its failure rate was lower than the failure rate of the original station, but after the operation began, the failure rate would increase significantly. This suggests that in times of war, due to the inherent unpredictability, logistics support cannot simply rely on proportional formulas, but requires more precise engineering assessments to adapt to the changing conditions of system use under distributed maritime combat conditions.

To meet the requirements of distributed maritime operations, the U.S. Navy is likely to need to reserve repair parts or surge industrial capacity to meet demand. However, an analysis of the naval aviation supply chain shows that some weak links in industrial enterprises will limit the ability to increase production in an emergency. For example, a review by the U.S. Department of Defense Inspector General of five key supply parts for the F/A-18 found that due to the obsolescence of some parts, a single supplier and multiple factors from industrial enterprises, the U.S. Navy and the Defense Logistics Agency could not obtain enough parts to meet the current gap and projected demand. Other reports show that the F/A-18EF will face a reduction of at least 18 supply sources and material shortages in the next two years.

The Defense Logistics Agency obtains the funds needed to fulfill its mission through revolving funds, a rolling funding arrangement that allows the Defense Logistics Agency to purchase products based on the needs of the military services and is also established to allow the military services to pay only for products that are known to be needed. Working capital funds are targeted to have a net balance of zero each fiscal year, which limits their ability to plan for long-term wartime needs. Currently, the Navy’s working capital is in flux, with negative balances expected in the future. As of the end of fiscal year 2021, the fund had a negative cash balance of $1.1 billion. To rebalance the fund, the Navy has adopted a variety of strategies, including redesigning the pricing system and introducing outfitting assurance measures. These efforts are likely to further delay the time to raise funds for parts needed to meet surge demand.

Response strategies for aviation parts supply chain

To alleviate the problems of the aviation maintenance parts supply chain, the Navy plans to respond from three aspects: grasping wartime needs, improving funding mechanisms, and saving funds to invest in future needs.

Accurately grasp wartime needs As the ability to process massive amounts of data and run numerous reliability models continues to improve, the U.S. Navy hopes to more accurately predict failure rates and, in turn, more accurately assess future needs. However, even models that use big data technology and extensive data collection are still limited by assumptions and data gaps. Predictive maintenance relies on the accumulation of data, and the problem is that predictions must cover a range of situations that are not usually encountered. Aerospace maintenance agencies are looking to use machine learning and other technologies to identify rare but important failure items. However, the key issue here is not rare failures, but unknown environments.

Combat models may have practical utility in evaluating the relative performance of systems because they can identify key systems in the kill chain, thereby focusing attention on the systems that are most needed for combat readiness. Methods that focus on kill chain elements, coupled with engineering analysis of similar systems, may form more regular failure modes. For example, when the victory or defeat in an air battle depends largely on the radar’s search accuracy, targeting capability, and the successful launch of air-to-air missiles, the key links in the kill chain have become very clear. And direct data on these elements may have been mastered, such as relevant information on the search radar. Therefore, the next step may be to find components that are common to those rarely used elements in other systems. Next, it may be necessary to evaluate the possible impact on the entire kill chain when a less used but critical component fails. If certain components are critical, but their basic characteristics are not yet clear and difficult to test effectively, the next step is to find engineering solutions or consider purchasing spare parts to ensure the stable operation of these critical systems. Therefore, the demand signal must be constructed from the position of the component in the supply chain, rather than the demand observed when it is not used in the kill chain.

Systems are often tested on site before delivery, which is expensive. As long as the steady-state environment can provide test conditions close to the real world, there is no need for additional testing. However, for combat systems that are rarely used in daily life, the steady state does not reflect the real combat environment. Field testing in a real environment close to actual combat can provide better engineering and demand models, and thus make more realistic assessments of required inventory levels.

Proactively improve the funding mechanism If steady-state demand accurately reflects wartime demand, then the working capital mechanism is an ideal choice for fixed spare parts investment. Spare parts procurement is based on long-term operating experience and steady-state demand forecasts, which can provide sufficient quantities when needed. Because the basic capacity of spare parts is linked to known demand, companies have a continuous incentive to ensure capacity. However, when steady-state demand is different from wartime demand, the inventory level of working capital procurement may be insufficient.

The legislation related to working capital puts the responsibility at the level of the Secretary of Defense, and the U.S. Navy cannot decide on its own to stop using working capital as a payment mechanism for the Defense Logistics Agency. Therefore, it is more pragmatic for the Navy to accurately decide where to use working capital and where to seek other solutions. In practice, the U.S. Navy generally uses working capital when DLA bulk procurement is most economical and effective, and uses other mechanisms when other mechanisms are more effective.

This approach requires adjustments to the way plans and budgets are submitted. The total demand for spare parts cannot be viewed as the maintenance parts that the Navy expects to consume in a planning or budget cycle. It is necessary to ensure that the quantities purchased can reliably support the operation of the kill chain and meet the needs determined by engineering models, field testing, and repeated examples of mission execution failures. This may mean that some parts will be purchased entirely to respond to major but relatively low-incidence events such as war. For these parts, the procurement mechanism will be similar to that of weapons procurement. Operationally, certain types of spare parts can be clearly identified as "kill chain essentials" and included in the program costs, and the program office can directly contract with the supplier, so that the DLA does not need to intervene. Doing so may lose some scale advantages and force the services to conduct supply chain assessments in an ad hoc manner. However, for critical parts that are in the highest demand but are not essential to complete the kill chain, relying on the DLA and working capital mechanisms is still the best choice.

Save money to invest in the future Legacy legacy aircraft remain an important part of the steady-state operations of the US joint force and will remain so for some time to come. However, these aircraft are expensive to maintain and the costs will gradually increase as the aircraft age. In addition, these old aircraft are generally useless in a near-peer confrontation, so to some extent, the issue of "saving" and "not saving" reflects the trade-offs and choices of current and future combat readiness.

Although old aircraft can be fully guaranteed during peacetime deployment, they cannot be expected to undertake surge missions in wartime, when a large amount of funds will tend to the Marine Corps and F-35 combat units. Given the change in the priority of F-35’s tactical air support needs in wartime, the steady-state-oriented contract maintenance model should be abandoned and a wartime savings model without contract incentives should be adopted to better adapt to changes in wartime needs. The contractor-supported incentive program has all the shortcomings of the Defense Logistics Agency model, that is, it is too focused on short-term interests and actually weakens the contractor’s willingness to hold parts that may only be used in wartime.

Summary

Analysis of the ammunition supply chain shows that in a distributed maritime combat environment, due to many production and supply chain constraints, the U.S. Navy has extremely low production rates and inventory levels of key ammunition required for combat with comparable competitors, which cannot meet the expected demand in the event of a conflict. In addition, since the U.S. Navy also shares production lines for some ammunition with the Air Force, this will lead to severe challenges for the two services in conflict preparation and it will be difficult to ensure sufficient ammunition supply at the same time. To effectively address the challenges facing the ammunition supply chain, mitigation strategies need to be analyzed from three time dimensions: short-term, medium-term, and long-term, and the possibility of conflict and related risks should be evaluated simultaneously. If a conflict breaks out in the short term, there will be little time to invest in additional inventory, new production capacity, or emerging technologies. Therefore, the short-term strategy focuses on the reallocation of ammunition and a surge in production; the medium-term strategy has more time to accumulate inventory and can increase supply by expanding production capacity; in the long term, the U.S. Navy will invest in emerging technologies such as modular design and additive manufacturing to achieve cost reduction and efficiency improvement in ammunition production.

Analysis of the current supply chain for Category IX supplies in the U.S. Navy Aviation reveals a trend of over-reliance on short-term solutions to quickly restore near-term readiness, while neglecting necessary investments in long-term wartime reinforcement capabilities. This is reflected in the Navy’s approach to forecasting repair parts, incentive mechanisms for key stakeholders, and funding management mechanisms for procuring repair parts. An assessment of the capabilities required to support distributed operations at sea in a large-scale conflict with a near-peer competitor shows that the spare parts currently procured by the Navy are not the spare parts it needs to support operations. To address these issues, the response strategy should overcome near-term bias and adopt a targeted approach. On the one hand, more accurate engineering data and demand forecasts can be obtained through in-depth analysis of the kill chain system, which will help accurately grasp the real demand for spare parts in wartime; on the other hand, the financing mechanism should be properly addressed and spare parts investment should be rebalanced to adapt to changes in spare parts inventory demand in wartime in a more flexible way.

In summary, munitions are different from most social goods. Although they are critical in wartime, their use in peacetime is extremely limited. While demand is known in some cases, it is still very costly to stockpile and invest in products that are “for use only in war situations.” The Navy is currently focused on meeting steady-state demand and adjusting for near-term readiness needs. Demand indicators are primarily based on historical data analysis, taking into account conflicts over the past few decades, which is inconsistent with expected demand under distributed maritime operations. Although some recent Navy initiatives have attempted to better predict and meet demand, they have not yet been reflected in the Navy’s procurement and supply systems.

However, even if the Navy can improve its demand forecasting capabilities, problems with industrial enterprise capabilities will still limit its ability to respond to surges in demand. Due to the lack of manufacturing resources and shortages in material supply, the stability of the supply chain is seriously questionable and presents obvious vulnerabilities. Complex relationships and shared production lines make it difficult for relevant personnel, especially those below the second-tier contractor, to be aware of these weaknesses. Funding mechanisms, especially those that use working capital to support Category IX materials, make it difficult to procure or invest in infrastructure based on future needs. Therefore, the Navy still needs to address many issues such as planning layout, budget allocation, and industrial enterprise capabilities when formulating mitigation strategies.