The Bren machine guns are essentially the product of the British Empire’s attempt to support its global "military obligations" with limited resources in its decline. In its heyday, Britain had a territory of 37 million square kilometers, which was larger than the Mongol Empire of Genghis Khan, an area of India. The sun never set on its territory, and it was called the "Empire on which the Sun Never Sets". During this period, Britain had encountered some challengers, such as France and Russia. The British defeated them at Waterloo and Crimea respectively, and their position was as solid as a rock, and they remained the world’s largest country for hundreds of years. However, the end of the First World War shook the foundation of the empire. The First World War dealt a huge blow to Britain. After the war, it showed a clear trend of decline, which can be reflected in various aspects such as politics, economy, and diplomacy. However, the British government took many timely measures between the two world wars to rescue some social crises and try to support the global military hegemony of the British Empire. In this case, the emergence of the Bren Machine Gun Car was not accidental. Interestingly, although the Bren Machine Gun Car is an emergency military technology product, as a panacea on the battlefield of World War II, the Bren Machine Gun Car has undoubtedly achieved unprecedented success. This shows that as an old imperialist country, although Britain has begun to decline, it can still coordinate the complex relationship between military needs and military resources well. As the iconic equipment of the British Army in World War II, the Bren Machine Gun Car has been forgotten by most people today. But this ultra-light tracked armored combat vehicle with an extremely simple structure has an extraordinary story behind it.

R&D background

The birth of the Bren Machine Gun Car has a profound historical background. After the end of World War I, severe financial pressure and a general psychological state of war weariness prompted Britain to demobilize its huge army at a dangerous speed. In November 1918, there were more than 3.5 million soldiers in uniform (not including those paid by the British Indian government), and two years later they had been reduced to 370,000. After that, despite the heavy obligations it had assumed for the Empire and Europe in a series of postwar treaties, Britain’s annual defense budget and establishment were continuously cut until 1932. Not only were military spending and personnel numbers drastically cut, but most military-industrial enterprises were closed or converted to civilian production, and organizations above the division level were abolished. In fact, in terms of historical tradition, the army has always been in an insignificant position in the UK. The establishment of the British Empire relied on the powerful Royal Navy, and the army’s responsibility was mainly to maintain law and order within the empire.

Throughout the 1920s and early 1930s, British army military spending gradually decreased, reaching its lowest point in 1933, accounting for only 2.5% of national income. However, from 1931 to 1932, Japan launched the "September 18th" and "January 28th" incidents in China, and the Far East crisis broke out. The Far East Crisis fully exposed the loopholes of the British Empire in defense. The 1932 Defense Policy Assessment Report believed that the size, equipment quality and mobilization efficiency of the army were completely insufficient to fulfill the obligations under the League of Nations Covenant or the Locarno Treaty, and it was difficult to defend India or other eastern territories. In this situation, in 1933, Hitler came to power in Germany, and the European continent was once again shrouded in the shadow of war. Britain had to start rearmament, but during the entire rearmament period, the army was still the weakest among all the services. Chancellor of the Exchequer Chamberlain insisted that: "It is more advantageous to use our resources in the Air Force and Navy than to build a huge army." It is no coincidence that the Bren machine gun vehicle was developed and mass-produced as a standard equipment of the British Army in such a historical context. On the one hand, under the constraints of the Ten-Year Guidelines, the more than ten years of resource austerity made the British Army naturally favor cheap, simple-structured ultra-light armored vehicles. After all, without the obligation of continental defense, such equipment is sufficient to cope with the broad "colonial mission"; on the other hand, although after 1933, the British Army was able to get rid of the constraints of the "Ten-Year Guidelines" and resume its defense obligations to the European continent (although it was still a "limited obligation"), and expand and rearm accordingly. However, the limited additional resources were greatly diluted by the rapidly expanding size of the troops. In this case, only by continuing to use cheap, simple-structured ultra-light armored vehicles can the basic mechanization problem of the troops be solved.

The origin of "Carden Lloyd"

There is a direct technical origin between the Bren machine gun vehicle and the famous "Carden Lloyd" ultra-light tank. "Carden Lloyd" is a typical product of the "imperial defense" thinking after World War I. World War I not only greatly damaged the British economy, but also caused the British economy to remain in a state of decline and instability for more than ten years thereafter, and the speed and efficiency of industrial development declined significantly. Correspondingly, due to the victory of the war, the British Empire reached an unprecedented scale, and the already weak economy was burdened with too heavy an imperial burden. At the same time, the war also greatly affected the social psychology of Britain. People were full of fear and worry about the war. Preventing the outbreak of the war again became an important goal pursued by ordinary British people after the war. The pacifist movement was born and grew rapidly. Under the influence of various factors, the foreign strategic thinking of British decision-makers has also undergone subtle changes.

Affected by the war, the social psychology of Britain turned into fear of war and desire for peace. This social psychology, together with the slowly recovering economy, affected the strategic choices of British strategists. Avoiding war and pursuing peace at all costs became the starting point and end point of strategic choices. In fact, unlike the slow recovery of the economy and the social psychology of fear of war after the war, Britain’s strategic position has been improved to a certain extent due to the victory of the war. "Britain’s corresponding power and influence in the world have not been weakened by the war-Germany has been defeated, France has been weak and focused on continental European affairs, the United States has returned to its isolationist tradition after the war, the Soviet Union is focused on internal affairs, and Japan is still just a regional power... Only Britain has the strength of a global empire, and the navy has enough power to defend the empire."

Britain acquired a large number of German colonies after the war. Turkey’s collapse in the Middle East led to the control of Mesopotamian oil by Britain, thus Britain became a dominant country in the Middle East and Africa. The powerful British-French military alliance did not end with the end of the war. After the establishment of the League of Nations, Britain took a leading position in it. From this point of view, Britain still has strong comprehensive strength after the war; despite serious economic damage, Britain still maintains a relatively strong traditional financial and financial connection in the international market, dominates the huge resources of the colonial empire, and maintains its creditor status to European allies.

From the perspective of Britain’s role in international affairs, at the European level, before World War I, Britain had almost no binding obligations to European countries for most of the time. After the war, this situation changed. Since Britain fulfilled its international obligations in World War I, the end of the war did not relieve this obligation: the war turned Britain from a bystander or mediator into a participant. After 1917, Britain and France took on the main task of the war against Germany, while Russia temporarily withdrew from the European competition due to the revolution. The United States’ interference in European affairs was not so obvious, "Europe is still Europe for Europeans", and Italy’s role was negligible. In this way, at the Paris Peace Conference in 1919, Britain and France became the two major powers responsible for dealing with the German issue. Even at the Locarno Conference on European security in the mid-1920s, Britain still had to take on the role of being responsible for European security. From the perspective of the empire, with the introduction of the "Versailles Treaty" on the acceptance and trusteeship of the colonies of the defeated countries by Britain, France and other countries, the British Empire reached its historical peak in terms of scale. The territory of the British Empire extended from Asia to Europe, Africa, Oceania, and North and South America, becoming a veritable "empire on which the sun never sets". Compared with the "retreat" in economy and social psychology, Britain’s strategic position has been greatly improved, but this improvement highlights the asymmetry with the economic and social psychological conditions. From the European perspective, the current situation of the European continent requires Britain to assume the responsibility for the stability of the European continent after the war, but whether in terms of economic status quo or historical tradition, post-war Britain is simply unable and unwilling to assume this responsibility alone. From the perspective of the empire, the unprecedentedly large empire has become a problem for British strategists after the war. Like European responsibilities, the British economy after the war is simply unable to bear the burden of such a large empire. As a result, after World War I, Britain’s imperial policy and European policy had a certain contradiction. Under the circumstances at the time, only one of the two could be chosen. Under the influence of the social psychology of Britain’s unwillingness to interfere in the affairs of the European continent after the war and the priority of imperial interests, military strategy can only give priority to the empire, and in terms of European policy, it can only hope for the effect of diplomacy itself. So as mentioned earlier, under the guidance of the imperial defense thinking, the British Army showed great interest in ultra-light armored vehicles with simple structure, high reliability and low procurement cost - their military capabilities were sufficient to meet the broad needs of various "colonial missions", and they were economically affordable and adapted to the poor financial situation of the British Army and even the Imperial Government at the time. In fact, this so-called ultra-light armored vehicle that was favored by the British Army at the time has a special name term - tankette.

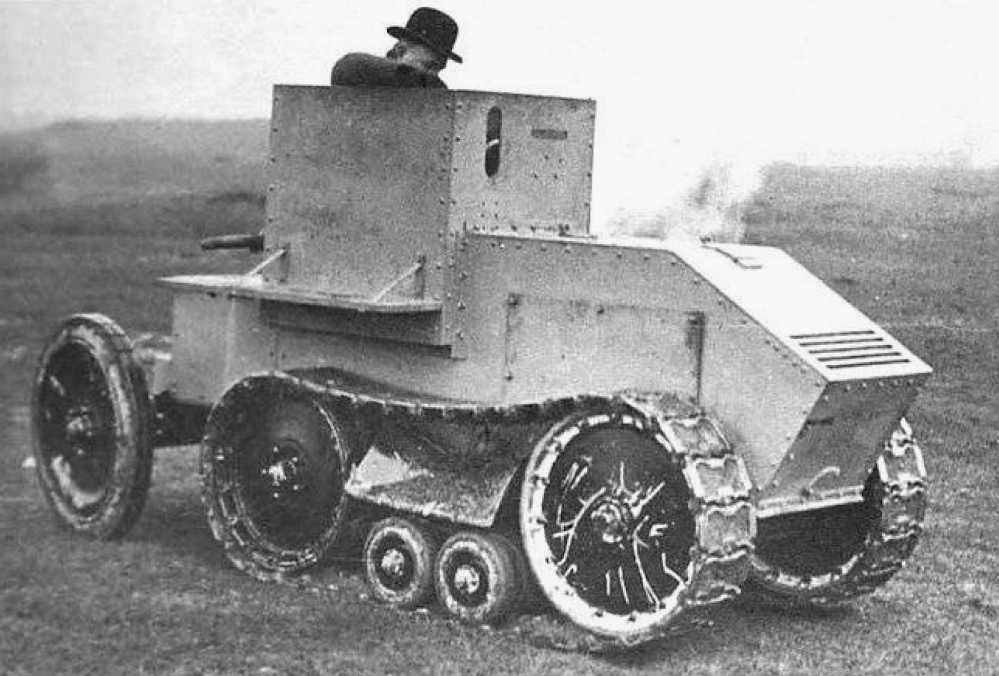

"Tankette" specifically refers to tracked combat vehicles with a combat weight of less than 5 tons, generally with an open design, and relatively weak armor and firepower. The earliest tankette concept in the world originated before World War I - that is, to install an iron plate-mounted machine gun on the Holt tractor for agricultural use, which was used to suppress enemy machine guns in trench warfare and protect the infantry. This concept was implemented in the early days of World War I. In 1914, a young Russian engineer named Alexander Borokhovshikov designed a "tracked off-road vehicle" with a total weight of only 3.6 tons. The vehicle had only one very wide track, a maximum speed of 42.6 kilometers per hour, a crew of one person, and a machine gun as a weapon. This little thing that looks quite weird is the earliest prototype of the "tankette" that can be examined so far. Another design that can be classified as a "tankette" during World War I was the Ford M1918 ultra-light tank developed by the United States at the end of the war. This micro-tracked armored vehicle weighing 3 tons, with a crew of 2 and armed with a 37mm gun or a machine gun, had the opportunity to become the first American tank to participate in the war, but General Pershing really looked down on this "tin can" and only used it as a tractor. In addition, General Jean Esting, the founder of the French tank force, once proposed such an idea: the infantry unit is equipped with a small tank that can resist shell fragments and small arms fire, while effectively assaulting the enemy. However, during World War I, his idea was not taken seriously and was never implemented.

After the end of World War I, due to many reasons mentioned repeatedly above, the British began to show their skills in the field of "tankette". In 1921, Colonel John Fuller of the British Army reiterated General Jean Esting’s ideas. Although the British military leaders did not agree with such suggestions at first, for conservative British officials, such a new thing was absolutely unacceptable before there was a foreign precedent. But Colonel Fuller’s idea impressed a young Army Major Giffard Martell, who was ready to design a single-person armored vehicle in accordance with the needs of the Army. Martell believed that in modern warfare, a single cavalryman could still gallop on the battlefield, but the warriors’ mounts were no longer war horses, but tanks that were driven by wheels or tracks and protected by armor. Martell was a practical man. After repeated experiments, he finally designed and manufactured a rare single-person tank in 1925. Martell’s single-person tank used a wooden body with an approximate size of 2.44 meters x 1.37 meters x 1.52 meters. It used an engine from the American Chrysler Corporation (then called Maxwell Corporation). Because the body was very light, the maximum speed reached 32 kilometers per hour. Martell only made a concept car. He tried to promote the concept of this single-soldier vehicle to the entire British Army, but it was obvious that his strength alone was not enough. The main sponsor, the British Morris Motor Company, cooperated with Martell to build a one-man ultra-light tank in 1926. The size of the tank body was not much different from the concept car, but it used a metal body, the armor thickness was 8 mm, and the vehicle weighed 2.2 tons. The vehicle was replaced with a Morris engine, equipped with a 7.7 mm machine gun, and had a maximum road speed of 35 kilometers per hour.

Although the British Army praised the excellent mobility and low cost of the one-man tank, it also found that it was difficult for only one crew member to complete driving and shooting at the same time. There were less than 10 one-man tanks called "Morris-Martell" equipped with the British armored reconnaissance and experimental armored forces. The "Morris-Martell" tank project ended here, and Morris Company turned to other fields. However, the one-man tank project made Martell famous, and in 1927, the Manchester-based Crossley Company extended an olive branch to him. The new tank developed by the two parties has a size of 3.05 meters x 1.45 meters x 1.62 meters, an armor thickness of 9.9 mm, a vehicle weight of 1.8 tons, and a weapon of 1 7.7 mm machine gun, using a 45-horsepower Crossley engine. The appearance of this tank is more like a half-track tank, with poor off-road capabilities and frequent failures. Therefore, it did not receive the favor of the British military and hastily ended its historical mission.

The flowers blooming inside the wall are fragrant outside the wall. Although Martell’s plan ended, the development of ultra-light tanks did not stop there. Just after Martell proposed the single-person tank plan, Carden Lloyd Tractor Co., Ltd., which became famous in the future, also began to develop similar tanks. In the mid-1920s, British John Valentine Carden and Vivian Lloyd began to design tankettes together. Carden Lloyd’s early works were not much different from Martell’s plan. They were all single-person designs (i.e. "Carden Lloyd" MKI/II/III/IV/V). The biggest feature was the use of a longer track suspension, which was more suitable for off-road walking and had excellent mobility. Subsequently, Carden Lloyd Company continued to improve on this basis and began to adopt a slightly enlarged two-person grouping design. Finally, in 1927, it created the "Carden Lloyd" MKVI ultra-light tank with higher usability. Later, Carden Lloyd Tractor Company and its tank design were acquired by Vickers Armstrong, and the two became designers of the company. The "Carden Lloyd" MKVI ultralight tank was able to be mass-produced and exported with the help of Vickers Armstrong’s resource channels. The size of the "Carden Lloyd" MKVI is 2.46 meters x 1.75 meters x 1.22 meters, with a total weight of 1.5 tons: equipped with a 7.7 mm Vickers heavy machine gun. A total of 450 vehicles were produced until the vehicle was discontinued in 1935, and it was also exported to more than a dozen countries in Europe, America and Asia, including China and Japan. The Carden Lloyd ultralight tank is the most successful design among the early ultralight tanks, and has become a design template for the production of ultralight tanks or light tanks in countries including Poland, Czechoslovakia, the Soviet Union, Japan, France and Germany. The British Army also used the "Carden Lloyd" MKVI to derive the so-called Bren machine gun vehicle during its military preparations in the mid-1930s.

The restoration of the "Continental Obligation", the financial difficulties and the development of the Bren Machine Gun Vehicle

Although the "Carden Lloyd" ultra-light tank has provided the minimum technical foundation, from the demand level, the development of the Bren Machine Gun Vehicle is closely related to the British defense plan to rearm before World War II, which first involves the restoration of the continental obligation. Since the signing of the Anglo-French Treaty in the early 20th century, Britain has assumed the responsibility of military obligations to the European continent, and the First World War is an important manifestation of Britain’s fulfillment of this obligation.

After the end of World War I, with the end of the war in Europe, the military threat from the European continent temporarily disappeared, and the "Ten-Year Rule" was also introduced in this context. At the same time, British decision-makers also The strategic goals of the army are divided into four levels according to the importance of priority:

Homeland defense;

Maintain overseas transportation lines;

Defense of the empire’s territories and internal security;

Defense of allies.

According to this defense order, the primary goal of the British armed forces is to meet the defense of the British Empire itself, and "continental obligations" become the army’s final goal. Under the guidance of the "Ten Years Rule" and the post-war British defense order, in the 1920s, Britain positioned the construction goal of the army only as defending the security of the homeland and the empire, without mentioning "continental obligations".

After that, in terms of the expenditure share of each branch of the military, the navy and the air force were given priority in accordance with the requirements of the defense order, and only a small amount of the army was maintained to meet defense needs. In non-war times, as long as there are 5 regular divisions, including a mechanized division, it is enough to complete the defense of the British Empire. As for the defense of the allies in the last layer of the defense order, the so-called "continental obligations" were abandoned. By the mid-1920s, although Britain had assumed the obligation to assist the invaded countries in the "Locarno Treaty", the construction of the army did not take into account the expeditionary force required to fulfill possible obligations. "As far as continental obligations are concerned, the various branches of the military can only express concern." In addition, in the view of British strategists, due to the "Locarno Treaty" The signing of the Treaty of 1927 would not require the fulfillment of continental obligations, which led to the British Cabinet’s stipulation on May 28, 1927 that "the British Empire will not be involved in a European war within the next ten years, and the army’s plan should be based on preparing for wars outside Europe."

In the 1930s, as the situation developed, the threat from Germany became greater, so the failure to prepare an expeditionary force for the "continental obligations" became the biggest flaw in the construction of the British Army during the "Ten-Year Rule". Therefore, the idea of rebuilding an expeditionary force was proposed in the report of the National Defense Munitions Committee in 1934, but it was opposed and questioned at the beginning. The Ministerial Committee on Disarmament believed that the army’s responsibilities were outside Europe and that the army should not be regarded as an important means used in European wars. Army Minister Hailsham believed that the army’s duty was to meet overseas needs, while the expeditionary force was composed of these troops used to defend overseas fortresses. The Chancellor of the Exchequer Chamberlain believed that Germany would not start a war on the Western Front in the next five years, so he suggested reducing the original army armament budget of 40 million pounds for the next five years to 19 million pounds. From a financial perspective, Chamberlain put the Air Force at the top of the reorganization of the three armed forces. In his view, the Army would only be the second echelon in national defense after the Air Force’s deterrent effect failed. In the end, the cabinet adopted Chamberlain’s view and revised the Army’s military budget for the next five years to 20 million pounds, of which 12 million was used for the Expeditionary Force.

In fact, under the circumstances at the time, British politicians and military leaders were unwilling to accept the Continental Obligation. Navy Minister Els Munsell and Dominion Affairs Minister Thomas even suggested that in order to prevent adverse effects on the public, the word "Expeditionary Force" should be avoided in public. As Prime Minister, MacDonald even said that the word "Expeditionary Force" should also be avoided in official documents. In March 1936, Germany marched into the Rhine demilitarized zone, and the situation in Europe became more tense. Soon, Belgium withdrew from the Locarno Treaty, and the northern gates of France were wide open. However, a wave of opposition to the "Continental Obligation" was raised in Britain. At the height of the reorganization of the Royal Air Force and the Royal Navy, the British finances, which had not yet completely recovered from the impact of the economic crisis, were simply unable to cope with the large-scale reorganization of the three armed forces at the same time. If the reorganization was blind, it might damage the economy. The "fourth branch of the military" Chancellor of the Exchequer Chamberlain insisted: "It is more beneficial to use our resources on the Air Force and the Navy than to build a large army."

British military scientist Liddell Hart advocated that Britain should return to the traditional blockade and consumption strategy relying on the navy, and that any military obligations on the continent would be "restricted responsibilities". After the situation changed dramatically, it would be foolish to send a small-scale expeditionary force. Subsequently, Britain redefined the mission of the expeditionary force according to the concept of empire rather than the concept of Europe:

Defend the homeland;

Defend overseas territories;

Defend treaty obligations;

Support France.

At the end of 1937, Britain once again determined a new defense priority procedure:

First is Britain’s domestic defense;

Second is Britain’s trade routes;

Third is the defense of overseas territories and assistance to the dominions

Finally, it is to jointly defend the territory of any allies that may exist in wartime.

British decision-makers still did not see the dependence on France until this time, and short-sightedly put continental obligations at the end of the defense order. Influenced by this principle, coupled with financial difficulties, the rearmament has led to the following situation: the Royal Air Force, which was planned according to the deterrence strategy, has been able to develop on a large scale, and the Royal Navy has also had a satisfactory expansion plan, while the army has remained almost intact. In addition, the reason why Britain introduced the military contraction strategy of the "Ten-Year Rule" after World War I was largely due to the consideration of the post-war economic and financial payment capacity. In the British military construction in the 1920s, economic and financial factors have always been the first consideration for military expenditure. The British mindset of incorporating financial conditions into military construction expenditure also greatly influenced the rearmament movement in the 1930s. In the 1920s, Churchill, who was in charge of the Treasury, imposed strict restrictions on military expenditures on the grounds of economic and financial conditions. As one of the main supporters of the "Ten-Year Rule", he repeatedly advocated extending the "Ten-Year Rule" in the 1920s. In the 1930s, although Churchill had left the government and became the biggest advocate of rearmament, Chamberlain, who was in charge of the Treasury, continued Churchill’s thinking in the 1920s that financial conditions determined the expenditures of the three armed forces. Even after he became prime minister, he still listed economic and financial factors as the premise for rearmament.

Although the "Ten-Year Rule" has been abandoned, the Treasury still stated that "it cannot be used to justify the defense department’s continued increase in spending despite the still severe financial and economic situation." They often emphasize that the rearmament plan cannot conflict with normal trade. The British government regards economic power as the "fourth service" of national defense. From the perspective of modern warfare, this view is reasonable, but under the circumstances at the time, facing the increasingly imminent threat of Germany, Britain’s top priority was to accelerate and increase large-scale rearmament. However, Britain turned the "fourth service" into a special service that was superior to the three services, emphasizing that large-scale rearmament would lead to economic and financial bankruptcy. Chamberlain considered the views of the Treasury too much and turned a deaf ear to the opinions of the three services. As a result, the Treasury actually determined Britain’s defense policy. Less than a month after Chamberlain became prime minister, he ordered the new Chancellor of the Exchequer, Simon, to transform the entire financial structure of rearmament. According to the procedure Simon finally proposed, the three armed forces should state the time required to complete their current plans, make their annual cost estimates, and also estimate the cost of maintenance and renewal required each year in the future. However, these figures are sent to the Treasury, which adds notes and the total amount of recommended expenses to the Defense Policy and Needs Committee established in 1935. The committee then determines the priority and sets the maximum total amount of annual funds for each branch of the military. Unless approved by the cabinet, the total amount shall not exceed the standard. The "quota allocation" system of the three armed forces comes from Simon’s report. "According to this system, when formulating budgets for the three armed forces, national defense must be subject to the ability to pay for finances, rather than maximizing financial resources to meet urgent national defense needs."

The Defense Munitions Committee pointed out in its report on February 28, 1934 that in order to make up for the deficiencies of the three armed forces caused by the "Ten-Year Rule", it is recommended to spend 71.32 million pounds in 5 years to make up for the deficiencies of the army, but Chamberlain believes that excessive increase in military expenditure will affect the economy and arouse public opposition. Increase in armaments should be within an economically acceptable range. Under strict financial constraints, Britain’s rearmament expenditure has always lagged far behind Germany. In 1937, Britain’s defense expenditure accounted for only 5.7% of national income, while Germany’s accounted for 23.5%; after 1937, the Treasury’s influence on the rearmament plan through Chamberlain has dominated the arguments of the Chiefs of Staff Committee and the Foreign Office. The speed and quality of rearmament were greatly reduced under the Treasury’s consideration. In short, since the rise of fascist countries in the early 1930s, although Britain has realized the necessity of rearmament and has successively introduced many ideas and plans for rearmament.

But these plans encountered many difficulties at the beginning. Not only did pacifists oppose large-scale rearmament, but the inherent strategic defense order and financial pressure also greatly hindered the rearmament. This led to a slow start and difficult progress in the British rearmament in the 1930s. But it was precisely this difficult situation that gave us a more comprehensive understanding of the British Army’s decision to use the "Carden Lloyd" MKVI ultra-light tank to develop the so-called "Bren Machine Gun Carrier" at that time-as a "Carden Lloyd" MKVI tankette. The cost advantage is inherent, and at the same time, this is a military design with great expansion potential.

The expansion potential of the "Carden Lloyd" MKVI can be seen from the evolution and development of its Soviet version T-27. In 1930, the Soviet Union purchased 26 early "Carden Lloyd" MKVI ultra-light tanks from Britain. In the Soviet Union, the vehicles were renamed 25-V (some archive documents call them K-25). At the same time, the Soviet government also purchased a license for mass production, and the Soviet version of the "Carden Lloyd" MKVI was named "T-27" on February 13, 1931, and was designated for production by two factories: the Bolshevik Factory in Leningrad, and the newly built Automobile Manufacturing Plant in Novgorod (later known as the GAZ Plant). The hull of the T-27 was made of riveted rolled armor, and some parts were welded, with two square hatches on the top. This ultra-light tank was equipped with a 7.62 mm 1929 DT machine gun. The T-27 ultra-light tank had no communication tools, and information between tanks was transmitted entirely by flag signals, which was also one of the characteristics of Soviet tanks at that time. It was equipped with a GAZ-AA four-cylinder gasoline engine (a copy of the Ford-AA engine) and a crew of 2 people. The production scale of T-27 was very impressive, with 393 vehicles produced in 1931, 1693 vehicles produced in 1932, and 1242 vehicles produced in 1933. Based on these T-27 ultra-light tanks, the Soviet Red Army established a total of 65 ultra-light tank battalions, each with 50 T-27 ultra-light tanks.

However, although the T-27 tank has a simple structure and is easy to operate, during the production and use process, the Soviets also recognized some defects in this tankette designed by the British. For example, due to the narrow track, it is not suitable for use in swamps and snow. In addition, the internal space of the T-27 tank is too small, only people with shorter stature can enter, and the firepower is also relatively weak, which limits its use on the battlefield. Based on these shortcomings, the Soviets tried to expand the combat potential of the T-27. For example, a small batch of self-propelled guns equipped with Hotchkiss 37mm guns were assembled at the Bolshevik Factory in Leningrad from 1932 to 1933. These self-propelled guns were built on the chassis of the T-27 tank, and some were equipped with a DT machine gun. Because the body was too small to accommodate too much spare ammunition, the ammunition used by the guns was loaded in a small trailer behind the tank. In 1932, the first T-27 was equipped with a 25mm flamethrower. This tank was tested in 1932 and 164 were produced in 1934.

In 1933-1934, the Leningrad Red Putilov Factory also used the chassis of the T-27 tank to design a self-propelled gun equipped with the 1927 model 76.2mm regimental field gun. The gun was installed on one tank, and the crew and ammunition were installed on another vehicle. Of course, this attempt was not successful. The weight and recoil of the 1927 76.2mm regimental field gun exceeded the T-27 chassis’s ability to bear, but this at least shows people’s evaluation of the Carden Lloyd MKVI chassis. Although the effort to move the 1927 76.2mm regimental field gun onto the T-27 chassis failed, in 1933, a T-27 self-propelled artillery equipped with a 76mm recoilless gun designed by artillery engineer Petropavlovsky was developed. However, although it successfully passed all the tests on the proving ground, it failed in the military test because of its poor ballistics and dangerous when firing. Of course, some people believe that the reason why this self-propelled recoilless gun based on the T-27 chassis was abandoned was also related to the stagnation of the development of related recoilless gun weapons after Boris Petropavlovsky himself died of illness in 1933. Surprisingly, the Soviets even tried to put a 284mm rocket weapon (the so-called "tank torpedo") on the chassis of the T-27... Although most of these attempts to "magically modify" the T-27 were unsuccessful, this shows from one side that the "Carden Lloyd" MKVI does have a relatively abundant military potential. It is precisely because of this that, as the country of origin of the "Carden Lloyd" MKVI, in the mid-1930s, it was natural for the British Army to reuse the tankette, a product of the "Ten Years Rule", to cope with the military challenges after the restoration of the "Continental Duty".

(To be continued)