One of the main reasons why the United States did not sign the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea is that it believes that signing the convention will not help the United States gain more benefits and freedom, but will "restrict its hands and feet" to a certain extent. The United States can completely rely on its strong maritime forces to achieve its goals. The cover shows the USS Ronald Reagan and the 5th Carrier Air Wing operating in the South China Sea in 2019.

2022 is the 40th anniversary of the birth of the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (hereinafter referred to as the "Convention"). As an important international convention regarded as the "Ocean Charter", the Convention has set guidelines for how countries use the ocean and its natural resources since its birth in 1982, and has also created a mechanism for resolving disputes. However, it is well known that the United States is not a member of the Convention, but it frequently regards itself as a defender of the Convention and condemns China, a member of the Convention. So, is the United States a defender or destroyer of the international maritime order? This requires us to comprehensively examine the US maritime policy from the perspective of national interests and global maritime order.

The development of the US marine policy

Since the founding of the United States, the marine legal system and marine policy have been deeply influenced by the concept of "freedom of the seas". This concept proposed by Dutch jurist Hugo Grotius in the early 17th century emphasized that the ocean cannot be regarded as property and owned by anyone, and the ocean is always open to free trade and exchanges between countries. Along with accepting the concept of freedom of the sea, the United States also accepted that it could exercise jurisdiction in the marginal waters of 3 nautical miles in the same way as governing land, which was the common practice for countries to determine the width of territorial waters in the 18th century. It was not until the end of World War II that the United States began to undergo major changes in its marine laws and policies after realizing that there were a large amount of resources such as oil and natural gas on the offshore seabed.

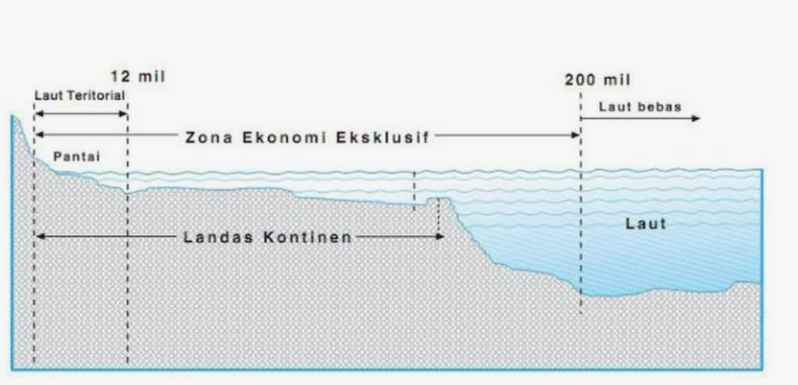

In 1945, then-President Truman issued a statement announcing that the natural resources adjacent to the continental shelf under the high seas belonged to the United States, and the United States exercised jurisdiction and management over them; in 1953: The US Congress passed the supplementary law "Outer Continental Shelf Land Act", stipulating that the seabed and subsoil on the outer continental shelf belonged to the United States. In addition, since the late 19th century, with the destruction of marine fishing grounds by industrial development, coupled with excessive and improper fishing and hunting, the US government was forced to begin interfering with marine fisheries and marine protection. By the 1970s, the United States had improved the legal system for the management of marine and coastal biological resources by strengthening federal and state legislation and signing international agreements.

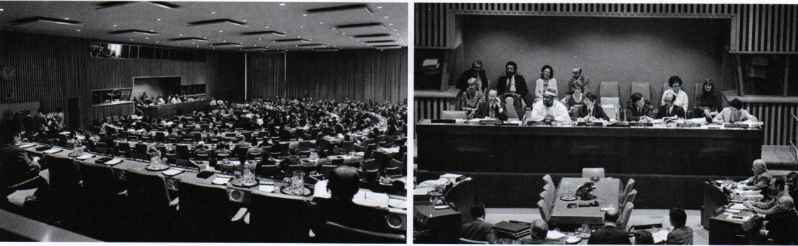

In the 1970s, with the support of the United Nations, the international community launched an agenda to formulate international maritime law. At the third United Nations Conference on the Law of the Sea held in 1973, the United States, as the main negotiating country, actively participated in the drafting process of all articles of the draft Law of the Sea. The goals of the third United Nations Conference on the Law of the Sea include: safeguarding the interests of maritime countries, protecting freedom of navigation, establishing a 200-nautical-mile exclusive economic zone, and establishing a deep-sea mineral resource system. The draft of the International Law of the Sea was finally completed in 1982. The global energy crisis in the early 1970s also caused the United States’ marine policy to shift to the goal of energy independence. Compared with the development of marine resources, the priority of policies such as marine protection and coastal zone management naturally decreased.

The Reagan administration, which came to power in 1981, began to strongly oppose policies that restrict marine development activities, which was also reflected in the Reagan administration’s opposition to the Convention. Because it disagreed with the provisions of the Convention on international seabed mining, it announced in 1982 that it would not sign the Convention on the Law of the Sea. Despite this, the United States’ domestic marine legislation continues to develop, gradually absorbing new systems created by international maritime law, such as the 12-nautical-mile territorial sea and the 200-nautical-mile exclusive economic zone. In 1976, the United States passed domestic legislation to establish the 200-nautical-mile fishery management boundary. In 1983, the United States announced the 200-nautical-mile exclusive economic zone of the United States through a presidential statement, and exercised supreme authority over the biological and non-biological resources within this range; it also announced that the United States would exercise and maintain the freedom and rights of navigation and aviation around the world, and oppose other countries’ "attempts to restrict the freedom of navigation and overflight." In 1988, Reagan issued another statement, amending the previous 3-nautical-mile territorial sea of the United States and establishing a 12-nautical-mile territorial sea system. However, unlike the provisions of the Convention, Reagan’s presidential statement waived the United States’ jurisdiction over marine scientific research within the 200-nautical-mile exclusive economic zone. This initiative to waive jurisdiction also indirectly reflects the United States’ tendency to maintain the maximum freedom of navigation.

After the 1970s, the U.S. marine legal system and marine policy have been gradually improved, with legislation to protect marine mammals, promote marine fishery management, control marine pollution, and establish marine protected areas and estuarine research and protection networks. In the field of promoting marine oil and gas development, the United States has revised the Outer Continental Shelf Lands Act several times to promote offshore oil and gas development and make it an important domestic energy source.

After the 1990s, with global warming and its related impacts on coastal zones, sea level rise, coastal erosion, and increased frequency of marine natural disasters, the U.S. marine policy faces new challenges. Among the many challenges, the challenge of global marine freedom of navigation and route safety has a particularly great impact on the U.S. marine policy. After the end of the Cold War, although the possibility of war between major powers has been greatly reduced, conflicts in global regions have increased, the threat of terrorism has increased, and the global threats faced by the U.S. Navy have become increasingly complex. Ensuring freedom of navigation and overflight in global waters is particularly important for the U.S. maritime force.

In addition, after the birth of the Convention, the vast majority of developing countries gradually awakened to the awareness of ocean jurisdiction and adopted domestic legislation to strengthen their claims to ocean rights and interests. The United States regards the claims that are unfavorable to itself as "excessive ocean claims" and conducts diplomatic protests and military challenges through domestic policies. However, since the United States is not a member of the Convention, its voice in current international ocean affairs is inevitably weakened, and the outward influence of the United States’ ocean policy is also disturbed. Although the United States has always claimed to abide by the rules of customary international law consistent with the Convention, it is outside the international treaties accepted by the vast majority of countries. This has always been the soft spot of the United States’ ocean policy.

Why did the United States not sign the Convention?

The United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea is regarded by the international community as the "ocean constitution" and represents an unprecedented achievement in the compilation and development of international law. The Convention officially came into force in 1994 and has 168 members to date. The Convention sets out guiding principles for how countries around the world use the ocean and its natural resources, and also includes mechanisms for resolving disputes. The United States has not signed the Convention, and Congress has not completed the ratification process, so the United States is not a member of the Convention. Like the United States, the coastal countries in the world that are not members of the Convention currently include: Turkey, Israel, Iran, Syria, Venezuela, El Salvador, Libya, Cambodia, Peru, North Korea, the United Arab Emirates, Eritrea and Colombia, etc. 13 countries.

The United States was once an active advocate and promoter of the Convention, and invested a lot of effort in the formulation of the Convention. It actively participated in the consultation and formulation process of the Convention at the Third United Nations Conference on the Law of the Sea held from 1973 to 1982. But in 1982, the Reagan administration issued a statement declaring that it had major dissatisfaction with Part XI of the Convention and its annexes. Part XI of the Convention is about the "International Seabed Area System", which stipulates that the international seabed area and its resources are the "common heritage of all mankind", and the exploration and development of mineral resources should be carried out in parallel by the mining country and the "enterprise department" representing all mankind: the mining country not only has to bear a lot of expenses, but also has to bear some "compulsory technology transfer" and provide deep-sea mining related technologies to developing countries free of charge. The Reagan administration believes that these provisions in the Convention violate the interests and principles of industrialized countries.

However, the US government also recognizes that the Convention contains provisions on traditional uses of the ocean, which generally confirm the existing international marine legal system and customary law. Therefore, Reagan established the United States’ 200-nautical-mile exclusive economic zone and 12-nautical-mile territorial sea in accordance with the provisions of the Convention, and announced that the United States would implement the Convention as international customary law. In 1994, the United Nations adopted an agreement on the implementation of Part XI of the Convention, which was amended in accordance with the opinions of the United States and other industrial countries. In the same year, then-US President Clinton sought the approval of the Convention in Congress but failed. Presidents Bush and Obama later urged Congress to ratify the Convention, but were unsuccessful. Despite this, successive U.S. governments have enacted many domestic laws and regulations that are consistent with the Convention.

The main reason why the United States has not yet ratified the Convention is the opposition of Congress, which also reflects the orientation of the United States’ national interests from another perspective. The forces in the United States that support the Convention (mainly the Democratic Party) believe that: ratifying the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea will benefit the United States more, including helping to enhance the United States’ ability to develop continental shelf resources, exploit seabed minerals, ensure freedom of navigation, and intervene in maritime disputes; joining the Convention will also give the United States moral and political authority in international relations and strengthen the United States’ credibility on the international stage. Not signing the Convention will only put the United States in an embarrassing and weak position. In addition, some American business groups, including oil, energy, shipping, fishing, and communications industries and environmental organizations, are also lobbying in Congress, emphasizing that not joining the Convention will undermine the United States’ commercial and strategic interests.

In response to the maritime differences and interactions between China and the United States in the South China Sea, in 2012, then-US Secretary of Defense Panetta stated in Congress that not joining the Convention made it impossible for the United States to effectively support its allies on the South China Sea issue. Obama also said that the Senate’s refusal to ratify the Convention would make it "difficult for the United States to urge China to resolve maritime disputes in accordance with the Convention."

There are also strong voices criticizing the Convention in the United States (mainly Republicans). First, the opposition believes that the Convention has serious flaws and will infringe upon the sovereignty of the United States and transfer the sovereign interests of the United States to international organizations and arbitration tribunals. The United States can completely protect its maritime interests through strong maritime forces instead of protecting its rights by joining the Convention; second, the opposition does not agree to hand over the power of international seabed mining to international mechanisms. They believe that the Convention gives the International Seabed Authority too much power in mining. The provisions of the Convention on the joint bearing of mining royalties are actually equivalent to taxing seabed exploration companies, which is a damage to the interests of the United States; third, the opposition believes that there is no need to join the Convention. Existing international customary law and other agreements have provided sufficient legal basis for international maritime law. Joining the Convention will not give the United States more maritime rights or freedoms.

Currently, the Biden administration has not initiated any action to join the Convention, but Biden himself has expressed a positive attitude towards joining the Convention. In 2007, Biden, then a senator, held a hearing as the chairman of the Senate Foreign Relations Committee to promote President Bush’s proposal to join the Convention. He declared in the Senate: "The United States is the world’s major naval power and trading power. The freedom of navigation of military and commercial ships at sea is indispensable to the national security and economic security of the United States. The navigation rules set by the Convention are conducive to these interests." "The Convention will not only not threaten our sovereignty, but also ensure and extend our sovereign rights."

Although the United States is not a member of the Convention and is unlikely to join in the near future, it has used other means to ensure its deep seabed mining activities. The United States currently claims rights to international seabed areas based on domestic law and signs bilateral or multilateral agreements with other countries to ensure its claims to international seabed resources. According to the United States’ Deep Seabed Solid Mineral Resources Act, the United States can authorize American citizens to explore and develop the seabed, which is also a unilateral hegemonic practice of the United States that goes beyond international law.

For a long time, the United States has been in a leading position in international maritime affairs. The United States has been in a leading position for most of the time during the first United Nations Conference on the Law of the Sea in 1958, the second United Nations Conference on the Law of the Sea in 1960, and the third United Nations Conference on the Law of the Sea from 1973 to 1982. However, after the birth of the Convention, the United States’ policies have instead exposed more conservative tendencies, turning to more unilateral domestic marine legislation and marine policies to achieve its national interests, and even increasingly taking unilateral economic sanctions to achieve its goals. After the implementation of the Convention, the United States only ratified the 1995 United Nations Agreement on Straddling Fish Stocks and Highly Migratory Species and the 1992 Framework Convention on Climate Change. The United States did not ratify or advocated the non-applicability of important international agreements on global marine affairs, such as the 1997 Kyoto Protocol, the 1993 Convention on Biological Diversity, the 1992 Agenda 21, and the 1995 Global Programme of Action for the Protection of the Marine Environment from Land-based Activities. Moreover, the United States often takes unilateral sanctions against countries that do not comply with US policies in fishing and whaling activities.

As the world’s superpower in the ocean, the United States’ attitude towards the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea profoundly reflects the contradiction between idealism and realism in its foreign policy. Ocean issues are often global issues. Judging from the current international political situation, it is impossible for the United States to achieve its own interests independently of the joint efforts of the international community and rely solely on its superpower status. This approach itself is beneficial to superpowers from the perspective of strength, but is the current strength of the United States the same as in the 1990s?