This is an era of positive progress and pioneering. This is also an era of rapid progress, belonging to the brave. In the 19th century, with the basic completion of the European Industrial Revolution, with the help of steam engines and muskets, humans have initially opened up the transportation lines of major cultural circles around the world, and a brand new earth has gradually appeared before the world. However, they still don’t know much about the hinterland of many continents. At that time, geographers, faced with blank maps, couldn’t find cities, so they drew elephants...

This situation is destined not to last long. With the establishment of geographical societies in various countries, under the multiple stimulations of official colonial expansion, academic exploration of new knowledge and personal pursuit of honor, the Western world has set off a climax of exploring and conquering the world: climbing to the top of the peak that no one has ever reached; going to the hinterland of the continent that no one has ever set foot on; discovering unknown beauty has become the main theme of the moment, and these explorers have also become the heroes of the times, using their courage, perseverance and even sacrifice to create many amazing feats and thus be remembered by the world for a long time.

How should we evaluate these explorers? The so-called discovery is often just that it is finally known. At the same time, along with these explorations and adventures, there are also all kinds of unbearable past events such as imperialist colonial slavery and species extinction. However, leaving aside these discordant factors, the perseverance and enterprising spirit shown by those explorers can still become a precious spiritual wealth for all mankind. The significance of this may be just as Samuel Baker, who explored the Nile River, exclaimed when he solved the thousand-year-old mystery: "I suddenly felt how glorious our cause is!"

Our story starts with "Lawrence of Arabia", who can be said to be a very inspiring figure for us to understand those European expeditions and explorers in the late 19th and early 20th centuries.

Lawrence was a "British archaeologist, military officer, diplomat and writer". After joining the army in World War I, he successfully instigated and led the Arab uprising. He assisted Britain in disintegrating the Ottoman Empire with his military and diplomatic talents, and made contributions to the British Empire. This legendary graduate of the Department of History at Oxford University has excellent writing skills. It was his works that recorded his strange stories and adventures that earned him the reputation of "Lawrence of Arabia". Lawrence also translated the ancient Greek epic "Odyssey" into English. Although his translation has limited academic value, it also shows his talent. Regarding Lawrence’s great achievements during World War I, there was a movie titled "Lawrence of Arabia" in 1962, which won multiple Oscars. Compared to the exploration of the Antarctic and the Arctic by European explorers in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, as well as climbing Mount Everest, searching for the source of the Nile, crossing the Sahara, exploring Siberia and the Rocky Mountains, Lawrence’s legendary story has a more specific historical significance in the Arab region during World War I. He himself was also an officer of the British Empire, and his main achievement was not as an explorer of unknown lands. In fact, the geographical exploration of the Arab region had been basically completed by the time of Lawrence. But Lawrence’s legend should still be understood in the context of a slightly longer period of European exploration stories. If these specific differences are removed, they still have very similar characteristics.

The explorers’ sponsors

Historian Fernandez-Armesto believes in his book Pathfinders: A Global History of Explorations that by the late 19th century, the transportation lines between the major cultures of the world had been basically opened up, and there were very few completely unknown continents and nations. Therefore, the main purpose of explorers was no longer to discover new continents and nations (although such a possibility still existed, such as New Guinea and the South American jungle), but to further explore and refine the understanding of known areas, and to conduct large-scale exploration of uninhabited areas such as the polar regions. It is in the latter sense that Fernandez-Armesto said: "Scientific exploration, the desire to understand the earth and everything about it, replaced the opening of transportation lines as the main purpose."

In terms of the general trend of exploration activities at that time, Fernandez-Armesto made such a conclusion with reason. The historian Jirgen Osterhammel, who is known as the "Braudel of the 19th century", also said that in the 19th century, "due to the rise of oriental linguistics, ethnology, and comparative religion, the knowledge of the West about the non-European world has increased significantly." Osterhammel admitted that the knowledge of the "West" about the non-European world has not been balanced by the corresponding understanding of the "West" by the non-European world. However, once we try to enter the process of Europe’s acquisition of knowledge about the non-European world from a specific level, including the specific cases of European explorers in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, we will find that the situation is much more complicated. While scientific knowledge about the non-European world has been accumulated, the stories of most European explorers at that time are more like explorations or even adventures such as "Lawrence of Arabia" rather than academic careers seeking knowledge.

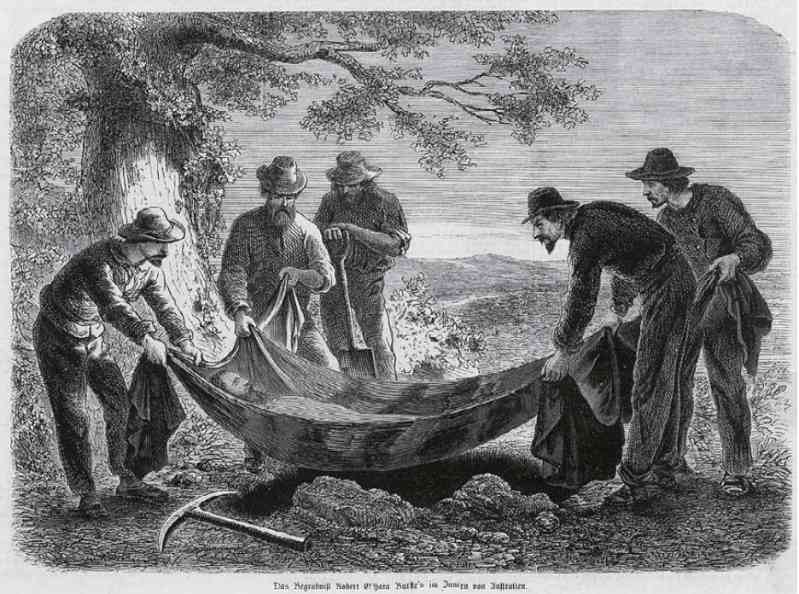

Any material or spiritual exploration must consider the survival of the explorer, that is, there must be a source of livelihood or financial support. When the explorers left us knowledge about the world, it is still meaningful to ask about the source of their funds. It should be noted that in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, there were indeed some self-funded or crowdfunded expeditions that were basically driven by curiosity or self-glory, although the purpose of the expedition was not necessarily related to scientific research. For example, the expedition that attempted to cross the Australian continent in 1860 was mainly funded by the citizens of Melbourne, followed by the support of the Victorian government. The expedition led by Booker ended in tragedy, and Booker himself died. In the words of Fernandez-Armesto, the most important legacy of this expedition across Australia is Ludwig Becker’s paintings, which "show the naked desert Gobi and the ruthless brilliance of the clear sky." Today, we can certainly say that this expedition across Australia has its value and significance, and it has also played a role in the accumulation of knowledge. I just don’t know whether such a summary by historians can be used as encouragement and comfort to the victims.

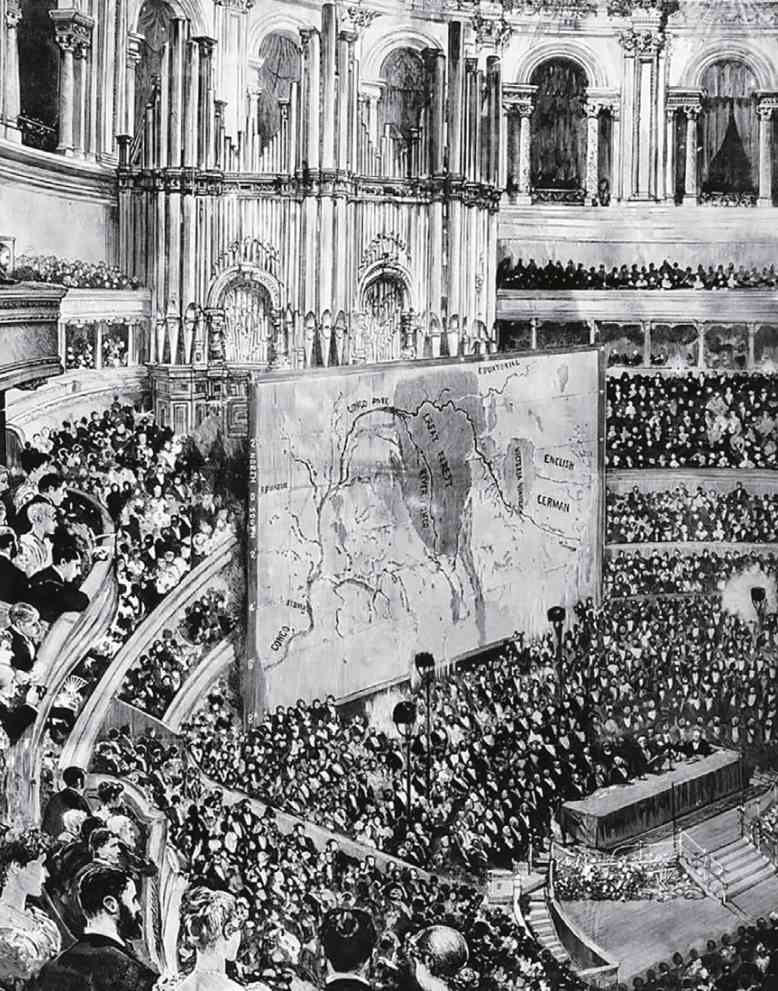

Most of the famous expeditions at that time, such as the search for the source of the Nile and the exploration of the polar regions, were mainly funded by the government, especially the Royal Geographical Society of Britain, which was established in 1830. Among the expeditions supported by the Royal Geographical Society, the most famous and influential one may be Darwin’s circumnavigation of the world, which is widely known for the latter’s epoch-making book "On the Origin of Species". In fact, the Royal Geographical Society was also the most important supporter in the exploration of the source of the Nile and the polar regions. In addition to the dramatic competition between explorers and the tragic personal heroism in the Nile source exploration and polar exploration stories, this is also an important factor that cannot be ignored.

Of course, it is too dogmatic to overemphasize the impact of funding support or even participation in specific organizational work on the content of academic output. We cannot discard Darwin’s "Origin of Species" as a product of the colonial era. But for European explorers in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, even if there is reason to distinguish them from "Lawrence of Arabia" in terms of specific time and space background, the investigation of their funding sources and sponsors still means that their exploration activities should be placed in a broader social, political and even global context for observation.

It is precisely because of this that the legend of "Lawrence of Arabia" provides an effective perspective. This perspective is also related to what Osterhammer calls "knowledge", but it is not natural or social science knowledge in an objective sense, but "knowledge" of the media and its dissemination.

The formation of cultural heroes

The name "Lawrence of Arabia" was derived from Lawrence’s excellent writing skills, but many European explorers were not very good writers, but they became the darlings of the newspaper and publishing industry, media stars and cultural heroes. For example, David Livingstone (1818-1873), a famous figure in the exploration of the source of the Nile, was originally a missionary to Africa, but compared with his job, he was undoubtedly more enthusiastic about exploration, and he did not think there was any contradiction.

"I regard the end of my geographical career as the beginning of my missionary career." Livingstone’s words can be interpreted in different ways. What is worth thinking about is the logical connection between geographical exploration and missionary career shown in this sentence. In any case, it was his practice of exploring in the name of missionary work that made him the most famous candidate for the Royal Geographical Society to explore the source of the Nile, and also made him one of the most famous cultural heroes of the Victorian era. His efforts to find the source of the Nile were objectively unsuccessful, and could even be considered a failure. But this is not important. What is important is that his story was successful, so much so that many places from Africa to Antarctica, from Britain to the United States are still named after him.

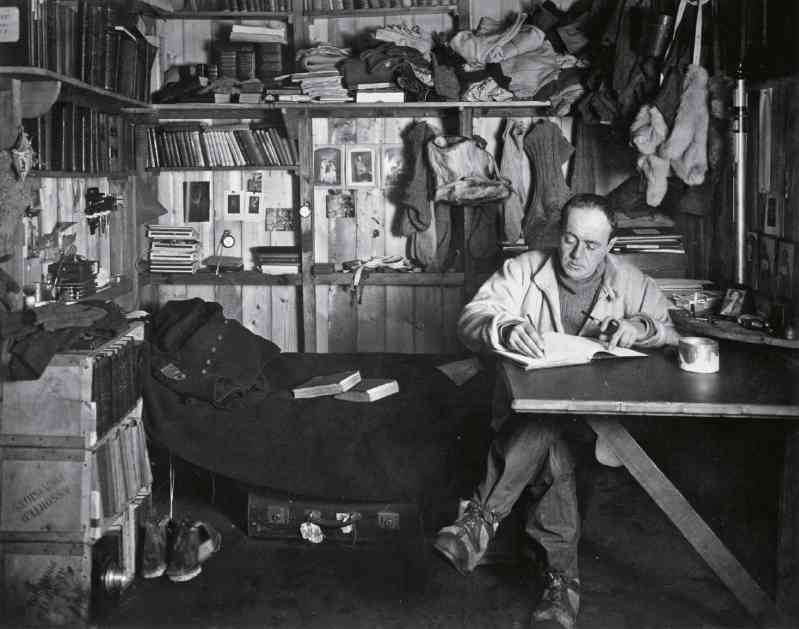

The famous explorer Captain Robert Falcon Scott (1868-1912) has more reason to become a cultural hero and is more well-known to Chinese readers. He led two Antarctic expeditions, but failed to reach the South Pole before the Norwegian Roald Amundsen, and eventually died on the way back, just a stone’s throw away from the base. This British naval officer possesses all the qualities to be a cultural hero, so after his quest for the South Pole ended in tragedy, he naturally became a typical example of the spirit and heroism of the British people.

It should be said that compared with Livingstone, who explored the source of the Nile, Scott’s story is actually more necessary to be fully understood, and his emphasis on scientific exploration is more praised by people. However, from their common experiences of fame during their lifetime and honor after their death, it is worth emphasizing that these explorers are not only explorers of natural or social science knowledge, but also cultural heroes shaped and admired by the media and the public.

In the past 30 years, themes related to travel and exploration in literary research have attracted more and more attention from scholars. Scholars have noticed that the European Age of Exploration was also an era of large-scale rise of travel and exploration literature, which included not only the works of explorers themselves, but also reports and literaryization of their heroic deeds. From a non-professional perspective, this undoubtedly helps us to have a deeper understanding of European exploration activities, or at least reminds us to pay attention to the shaping of these exploration heroes by the media and the public. Simply put, especially the European exploration activities in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, should never be boasted and worshipped only from the perspective of scientific knowledge accumulation, but should be viewed from a broader perspective, not only as the development of historical phenomena, but also as the creation process of historical memory. From this perspective, especially for Chinese readers, while being moved by the stories of Livingstone, Captain Scott, and "Lawrence of Arabia", without affecting the curiosity of people who share the same heart, they can and should ask, whose legends are these legends? Whose heroes are these heroes?

Not all stories have a beautiful summary

Such questions are not nitpicking, nor do they deny the contributions made by their efforts and feats to mankind, but they are necessary doubts. As Auden said in his poem, one of the common elements of such heroic stories is often that the explorers who are the protagonists of the stories "climb new mountains and name new oceans." With full respect for the accumulation of scientific knowledge, we have to realize that if this is the case, there are serious problems here. That is to say, when Fernandez-Armesto said that there were very few purely unknown continents and nations in the late 19th century, he only referred to what was known or unknown to Europeans. But from another perspective, we also need to realize that for the native people of Australia, even if they have never had the feat of crossing the continent in one go (let’s assume so), they at least have their own names for the mountains on the Australian continent and the seas around the continent in many cases. When European explorers came along and named the world, the exploration and discovery of the local people were not completely ignored, at least they had no time to consider.

In modern times, European-based exploration activities, with their specific knowledge-seeking standards, have indeed played a decisive role in accumulating knowledge about nature and society. However, once we look at the shaping of cultural heroes by the media and the public, some noteworthy prejudices entangled in them gradually become clear.

Let’s re-examine the European "exploration" of Tibet from this perspective. When Fernandez-Armesto introduced Tibet, he said that unlike the Arab region, Tibet "has been in isolation for a long time." Isolation is a relative term. Although transportation is not easy for the Central Plains due to geographical factors, the communication between the Central Plains and Tibet was relatively smooth at least when the Europeans arrived. The Central Plains, at least the Qing Dynasty, also had a relatively complete understanding of Tibet. However, European "explorers" basically would not consider passing through the Central Plains and borrowing the knowledge about Tibet that the Central Plains already had, but tried to enter Tibet in their own way, "for the purpose of humanistic research and knowledge." In the early days, the Qing government did not impose particularly strict control on foreign missionaries. By the end of the 19th century, after the Qing government tightened the entry of foreigners into the Tibetan area (except for missionaries from other countries such as France), the method of European "explorers" was first disguised, and then directly resorted to violence. From the perspective of knowledge production, such a process should be said to be worthy of deep thought and appreciation.

Reviewing the history of European exploration in the late 19th and early 20th centuries is not an easy task. On the one hand, as some European and American historians have summarized today, it was an era that made great contributions to the accumulation of global natural and social knowledge, and all future generations who benefited from global knowledge need to make correct assessments with an objective attitude. On the other hand, when faced with the individual cases of explorer stories at that time, some confusion is inevitable. Because it is obvious that not all stories are as neat and tidy as the beautiful summary. It is in this chaos that when trying to find and understand the history of exploration at that time, we find that the shaping of cultural heroes is at least as important as the production of objective knowledge.

It is worth noting that, just as European exploration activities actually gave birth to the theme of modern exploration literature, the memory of European cultural heroes at that time is still being shaped with the help of the prosperity of exploration literature. Take Lawrence as an example. His biographies have been endless since his lifetime, and new biographical works of him appear almost every few years. In our opinion, although the European heroes left behind in the late 19th and early 20th centuries are worthy of being remembered and studied, it may be time for them to return to their identity as the subjects of "one shilling biography".