The Confusion of the Nile River

The vast Sahara Desert divides the African continent into two parts. To the north are Egypt and the Maghreb, which are across the sea from Europe. From the beginning, this place has been part of the Mediterranean world. The remaining half of the African continent has become a mysterious "dark continent" in the eyes of Europeans.

Until the beginning of the 19th century, although more than three centuries had passed since the beginning of the great "geographical discovery", the interior of the African continent was still almost completely unknown to Europeans - "Geologists filled the blanks of the African map with barbaric scenes; on the uninhabited hills, where there were no cities, they drew elephants. The most fascinating question for European explorers at the time was where the source of the Nile River was.

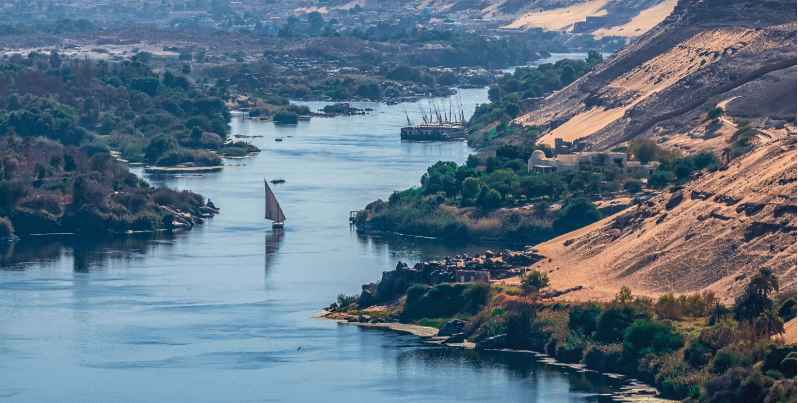

Of course, Europeans had long known about the existence of the Nile River. It was on the delta of the estuary of the world’s longest river that the great ancient Egyptian civilization was born. The periodic flooding of the Nile River not only provided sufficient irrigation for farmland, but also accumulated a layer of fertile silt, which was extremely conducive to the growth of crops, making this arid desert area a place where plants flourished and humans lived. Cradle. No wonder the ancient Egyptians had such a long poem to praise the Nile River: "Oh! Nile, I praise you, you flow out from the earth and nourish Egypt... Once your water flow decreases, people stop breathing."

The source of this great river is hidden behind the vast Sahara Desert. Around the 5th century BC, the Greek historian Herodotus explored the upper reaches of the Nile River, but only traveled a short distance before being blocked by the Aswan Falls, the northernmost of the six waterfalls of the Nile River. In the end, he could only vaguely speculate that the Nile River originated from four springs deep in the African continent. The emperor of the Roman Empire also sent a legion of two hundred men, but was still blocked by swamps and had no way to go. Ptolemy, a great geographer in the 2nd century AD, believed that the Nile River had two tributaries, both of which originated from lakes. Among them, the Blue Nile ( The White Nile (named after the dark blue water in the flood season) originates from a lake in the east, and the White Nile (named after the grayish white water) originates from some large lakes fed by the springs of the Moon Mountain. This information was probably spread to Ptolemy, who lived in Alexandria, Egypt, through the mouths of merchants doing business on the east coast of Africa.

More than a dozen centuries have passed. As late as the late 18th century, the secret of the Nile was only half revealed, and people successfully found the source of the shorter of the two tributaries, the Blue Nile. This honor belongs to the British explorer James Bruce. He was born in 1730 and was a prominent family in Scotland. Bruce married at the age of 24. But after only 9 months, his new wife died of tuberculosis. This was a big blow to the 1.9-meter-tall man. In order to avoid being reminded of the past, the Scotsman decided to travel overseas.

After living in Algeria for 2 years, Bruce began to roam North Africa and the Middle East. His biographer later wrote that at this time, "Mr. Bruce’s efforts were all about finding the most interesting career in his life." The source of the Blue Nile became his goal, and Bruce even learned Amharic (the common language in Ethiopia) for this. In November 1768, Bruce entered the Ethiopian Plateau. In addition to his secretary, several armed guards, three slaves and a guide formed this small expedition team.

The first place Bruce saw the Blue Nile was at the famous Tisset Falls (the second largest waterfall in Africa). He saw that the originally gentle river water suddenly turned into countless bubbles and rushed down with a rumble. From then on, 30 kilometers upstream, he arrived at Lake Tanna (with an area of 3,630 square kilometers and an altitude of 1,830 meters), and the source of the Blue Nile was within reach. In the end, Bruce discovered that the Blue Nile originated from a spring in a swamp south of Lake Tanna. When the tall Scotsman stood there, a sense of victory hit him: "From ancient times to the present, for nearly three thousand years, although some excellent scholars have appeared and spent countless efforts to explore, there is no result in the end, and now I am standing here!

In 1773, Bruce returned to London. He thought that his great achievement of finding the source of the Blue Nile would be respected. Unexpectedly, the London public opinion only regarded him as a Scotsman who "brought a lot of shocking news, and seemed to be exaggerated." Bruce’s record of the Ethiopian indigenous people eating raw meat cut from a living cow that was still dripping with blood was sneered at, so that the public opinion questioned whether "he had reached Ethiopia", which was tantamount to sentencing the explorer who had gone through hardships to death.

Until In 1790, James Bruce published "The Source of the Nile", which should have been published years ago. This time, everyone finally believed the authenticity of the author’s encounters and experiences in the book. Readers liked his brilliant writing and praised his courage. With the publication of this book, the source of the Blue Nile was unveiled, and the only thing left was the ultimate confusion of where the White Nile came from. In fact, among all the great rivers in Africa in the 19th century, the one that explorers were most eager to explore was not the Niger River or the Congo River, but the Nile River, which was regarded as the biggest trophy that explorers could win.

The Secret of Lake Victoria

In the 1850s, the Royal Geographical Society in London issued an instruction to two explorers: "Your main purpose is to start from Kilwa or any other place on the coast of Africa and go deep into the hinterland to reach the famous Lake Nyasa (Lake Malawi) as far as you can. After you have acquired all the information you may need in this regard, you must march north to the mountains marked on our map, where the Nile may be sourced. Your second great goal is to discover these sources".

The two explorers were named Richard Burton and John Speke.

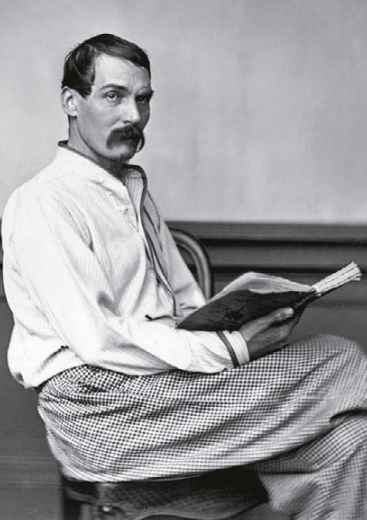

Richard Burton, born in 1821, was a language genius. He learned six languages before the age of 18. After a restless period at Oxford University (he thought he was much smarter than other students, and this attitude naturally aroused everyone’s disgust), Burton joined the army and served in British India for 8 years. He perfected his language skills in India, especially Arabic (this man may have mastered as many as 30 languages). At the age of 32, he began his famous expedition-disguising himself as a devout Muslim pilgrim, completing the pilgrimage to Mecca, and claiming to be the first European to do so.

The rebellious Burton was eager to gain the glory of exploration, so after obtaining the assistance of the royal geographer Ze Zheng, he set out on a journey to discover the source of the White Nile. But just before the expedition set off, a member of the team died. So Burton agreed to take a lieutenant on leave, John Speke. This man was 6 years younger than Burton and had a completely different personality. He was born into an old British family. He had a tall stature, blue eyes and pale complexion, and his demeanor looked very calm. He was far from an intellectual, and his exploration ability could not be compared with Burton. In fact, Speke’s greatest hobby was hunting. The purpose of his joining the army was to go to India to hunt tigers. The reason for following Burton to Africa is probably the same.

At the end of December 1856, Burton and Speke were on Samlombar Island (now part of Tanzania), about 20 miles off the coast of Africa. ) landed. At that time, slaves as far as the Congo Basin in central Africa were transported to Zanzibar and then sold to various parts of the Middle East and India. There they formed an expedition team of about 154 people (including 30 donkeys loaded with supplies). In June 1857, Burton and Speke landed on the African continent. They followed the route taken by the slave traders’ caravans, passed through the flat bushes on the coast, and reached the central plateau in a winding way. They were going to at least three lakes rumored to be where the Nile River might originate.

It was a difficult journey. Although they carried quinine, a special medicine for treating malaria, they failed to scientifically estimate the amount of quinine needed, and as a result, both Burton and Speke were infected. Malaria, with recurring fevers. Burton’s legs began to fester, and Speke was even worse, with some eye disease that temporarily blinded him. As the expedition began to enter the mountains, Burton and Speke were so weak that they often needed to be dragged by their companions to move forward...On February 13, 1858, they finally climbed a hill and saw a huge lake in front of them. Burton wrote: "The whole scene suddenly came into my sight, and I was filled with surprise and excitement... A wide lake was in front of me, the water was a very soft light blue, and the lake was about 30 to 35 meters wide. Miles... This is really an intoxication of the soul."

This is the scenery of Lake Tanganyika that Europeans saw for the first time. Burton was almost immediately convinced that this large lake was the source of the Nile, but Speke had doubts. When he heard that there was a lake larger than Lake Tanganyika in the north, Speke set out alone with a small team on July 10, 1858. Three weeks later, he stood on the shore of a vast lake, which was obviously much larger than Lake Tanganyika: "In the early morning, in the quiet atmosphere, the outline of the distant lakeshore appeared on the northern horizon. The compass direction was between west and north, but this observation still did not allow me to have a clear idea of the width of the lake. ... I no longer have any doubt that it is this lake beneath my feet that gave birth to that fascinating river (the Nile). The source of the Nile has long been the subject of much speculation and has become the target of many explorers.

Speke decided to name the lake "Lake Victoria" after the Queen of England. But his assertion that the Nile originated from Lake Victoria was questioned by Burton. After all, Speke only saw the lake but not the river. The latter wrote scathingly in his diary: "Although this lucky discoverer has a firm belief, his reasons are not convincing." However, the two people at that time were too weak to hold on, so they could only return to Zanzibar with unsolved mysteries. Speke was of course upset about this. Two years later, in April 1860, Speke traveled to the African continent again to confirm the correctness of his previous intuition. He explored the entire south and east coasts of Lake Victoria. On July 28, 1862, the British explorer finally discovered the possible source of the Nile on the north shore of Lake Victoria. Here, a spectacular waterfall (named "Ripon Falls" after the famous British politician George Ripon) flows into a wide river: "I saw that the Father River Nile undoubtedly originated from Lake Victoria. As I had predicted before, Lake Victoria is the source of this sacred river and the cradle of the first interpreter of our religious beliefs (referring to Moses in the Bible)." Therefore, after returning to Cairo, Speke immediately sent his famous telegram to London-’With the Nile, everything is fine! ’

’The remaining laurel leaf

On his way back north, Speke also met his old friends Samuel Baker (1821-1893) and his wife in the town of Gundu Kolu in southern Sudan. This was February 15, 1863. It was an exciting scene. Baker wrote: "We were all ecstatic and fired salutes as usual. The bullet shot one of my donkeys, which made a tragic sacrifice when we completed this geographical discovery. But the following conversation disappointed him greatly. The ragged Speke excitedly announced that the source of the Nile had been found - he found that the water of Lake Victoria flowed out from the narrow mouth in the north to form a river. Although he did not explore along the river for a long distance, he was sure that this was the Nile.

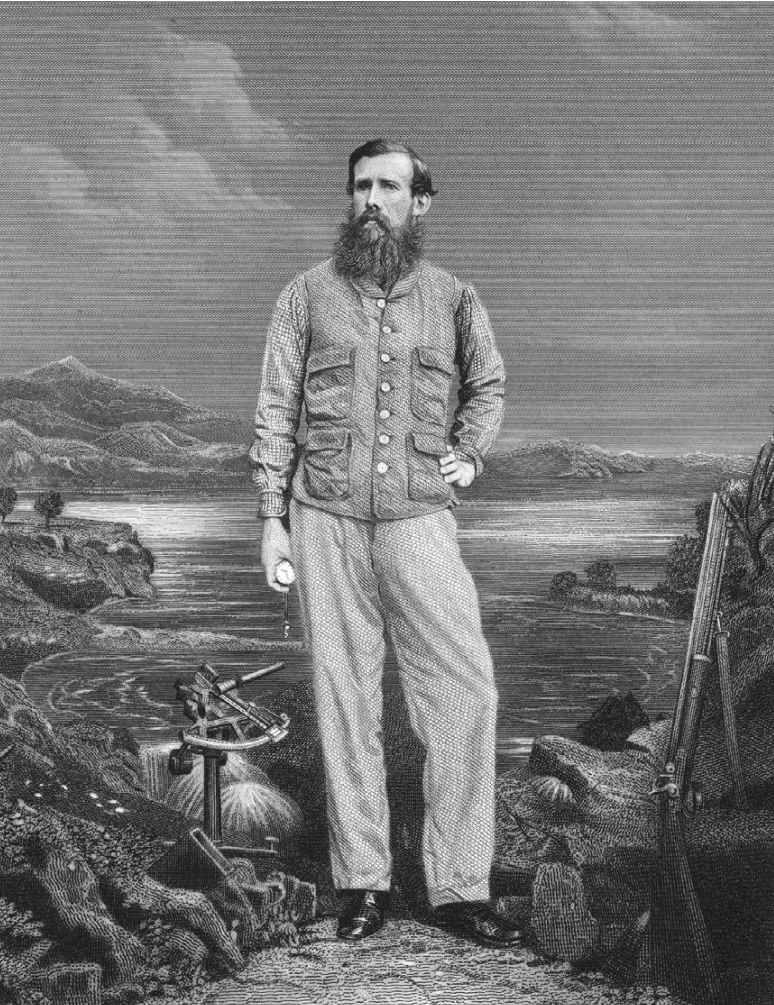

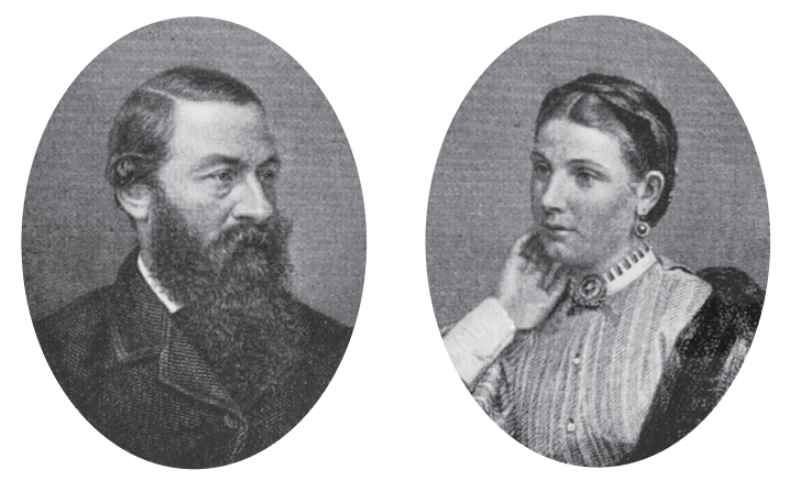

But this was also the purpose of Baker’s trip. He was a typical and very confident Victorian British man who loved adventure. When he was young, he went to Ceylon (now Sri Lanka) to take care of his own plantation and indulged in hunting there. After returning to Britain, Baker’s first wife died. Later, he went hunting in Asia Minor and supervised the construction of a railway in Hungary. At the same time, he married his second wife, Florence, a beautiful Hungarian blonde. In March 1861, the Bakers came to Cairo. At this time, Samuel Baker had only one goal, to find the source of the Nile River, "even if it means dying on the way!"

The expedition team formed by the Bakers was quite large, including 45 soldiers, 44 seamen and 11 servants. They were equipped with the best guns and scientific instruments and prepared sufficient food. The group set out from Khartoum on December 18, 1862, and went south against the Nile River. His plan was actually very simple, to go upstream from the known lower reaches of the Nile River and track its source.

After arduously passing through the southern Sudan swamps, one of the largest swamps in the world, where "suds" (floating grasses and aquatic plants) float in the river water and hinder the passage of ships. Baker realized that it was not surprising that his predecessors gave up exploring the Nile because of such terrible swamps. On February 2 of the following year (1863), 47 days after leaving Khartoum, the explorers finally got rid of the foul air of "suds" and arrived at Gundu Kolu. It was here that they met Speke during their rest.

Baker was very disappointed when he heard that his goal had been achieved by Speke first. He asked: "Isn’t there a laurel leaf left to reward me?" Fortunately, Speke’s answer was, "Yes. There is still a problem that has not been solved." He told Baker that when the Nile turned west near the Karuma Falls, he was unable to continue exploring along the river due to fatigue, lack of supplies and tribal wars in the area, and went directly north to Gundu Kolu. Speke also gave Baker a map and suggested that he find this interrupted Nile and explore a large lake in the legend of the locals, so as to make the exploration of the source of the Nile a complete success.

Encouraged by Speke, the Bakers continued to move southeast at the end of March to explore the unexplored area. Florence took off her heavy skirt and put on a shirt and loose trousers like her husband, buckled a belt, and wore high-top elastic shoes. Although she often suffered from malaria, she was an indispensable force in the expedition. She was responsible for arranging meals, managing servants and caring for patients. Although the local natives said that it was only a two-week journey from Gundu Kolu to the legendary lake, the Baker expedition took a full nine months because they had to grope in the wilderness. It was not until March 14, 1864 that the indomitable couple crossed a deep valley and reached a high ridge. Baker rode a cow (the horses were all dead) and walked in front of the team. At this time, according to his later description: "I suddenly felt how glorious our cause was. There was a large expanse of water far below the mountains, stretching infinitely to the south and southwest, like a sea filled with mercury glittering in the midday sun. About fifty to sixty miles to the west, green mountains rose from the lake, about seven thousand feet high.

It turned out that they had found the legendary lake. In order to show respect for the then British queen’s husband, Baker immediately named it "Lake Albert". Baker originally planned to let all the staff cheer three times in the British way to celebrate. However, he realized that he had found one of the two sources of the Nile River that people had been looking for for centuries. This made him very excited. He did not cheer three times, but thanked God for guiding and protecting them to overcome all difficulties and achieve such a great achievement.

In addition to Lake Albert, their expedition also yielded another reward. In early April, they continued to sail east in a small boat. After sailing for 18 miles, the river narrowed significantly and turned into a mountain gorge with 200-foot-high cliffs on both sides. Soon they arrived in front of the largest waterfall of the Nile River, where a snow-white curtain of water rushed down from a height of 130 feet in a 19-foot-wide rock crevice. Baker named this waterfall Murchison Falls in memory of Sir Roderick Imbe Murchison, the president of the Royal Geographical Society of the United Kingdom. At that time, Samuel Baker could not have imagined that when he completed this legendary expedition and returned to the "civilized world", he himself would be knighted by the Queen! The Royal Geographical Society also solemnly awarded him the Victoria Gold Medal. Throughout the United Kingdom, the determined "Nile Baker" and his brave wife were warmly praised and flattered by people. Their adventure deeds became the material for legendary fantasy works that the British public loved to hear and hear.

The most famous gathering in the history of exploration

However, the problem of the source of the Nile River has not been truly solved. It is true that Speke discovered Lake Victoria and correctly judged its relationship with the Nile River, but it cannot be said that "everything is fine with the Nile River". He did not actually explore the direction of the river flowing out of Lake Victoria, and could not prove that it was the Nile River. At the same time, he did not solve the problem of the source of Lake Victoria itself. For this reason, he was strongly questioned by his former exploration partner Burton after returning to Britain. In September 1864, the differences between the two had reached the point where they had to be resolved through public debate. Just one day before the scheduled debate, Speke, who loved hunting, died accidentally due to the misfire of his hunting rifle. What’s more tragic is that many people at the time suspected that he committed suicide because of guilty conscience... As for the Bakers, although they filled the gap from the lower Nile River to Lake Albert, they did not even reach Lake Victoria, and could not prove that the Nile River flowing out of Lake Albert and Lake Victoria was the same.

In the eyes of Sir Murchison, the president of the Royal Geographical Society, it was time to play his trump card. He wrote in the letter, "Now, there is a great geographical problem to be solved," and completing this work will surely "make your great experience of African exploration for many years more glorious and great." The recipient’s name is David Livingstone.

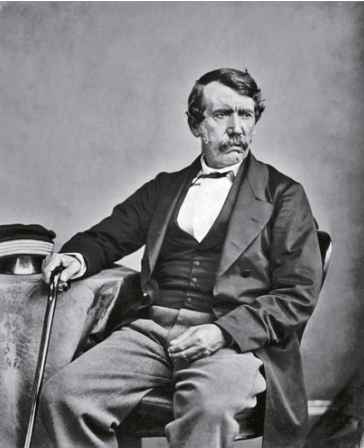

This is a great god-level figure in the African exploration community in Britain and even in the West. Livingstone is even revered by some as "the greatest explorer in human history." He was born in Scotland on March 19, 1813. Due to his poor family background, he worked as a child laborer in a textile factory at the age of 10. But Livingstone, who was eager to study, still insisted on studying in night school and finally entered the medical college. Soon after graduation, he was sent to southern Africa as a doctor and missionary, and landed on the African continent in Cape Town, South Africa in 1840.

Facing the magnificent rivers and mountains of Africa, Livingstone made such a bold statement: "We will own the whole world without any secrets." On August 3, 1851, Livingstone discovered the huge Zambezi River; in April 1854, he reached the Congo River; in November 1855, he saw the world’s largest Victoria Falls - it poured down from the cliffs and flowed into a narrow and deep canyon. The mist stirred up by the rapids formed a gorgeous rainbow under the sunlight. In May 1856, Livingstone arrived at the Portuguese Indian Ocean coast, completing the journey from west to east across the "Dark Continent" and across Central Africa, becoming the first European to cross the African continent. When he received the letter from Sir Murchison, Livingstone was already 52 years old, and after a long and arduous life of exploration, his body was very weak, but he still gladly accepted the suggestion and set foot on the unknown world of the African continent for the third and last time.

In the view of Livingstone, who was familiar with the topography of southern Africa, Lake Nyasa was likely to flow northward into Lake Tanganyika, which was connected to Lake Albert. The Nile River flowed out of Lake Albert, so Lake Nyasa was the real source of the Nile River. In view of this view, he decided to investigate along the northern shore of Lake Nyasa and then turn to the southern end of Tanganyika to determine the distribution and relationship of the water systems in this area.

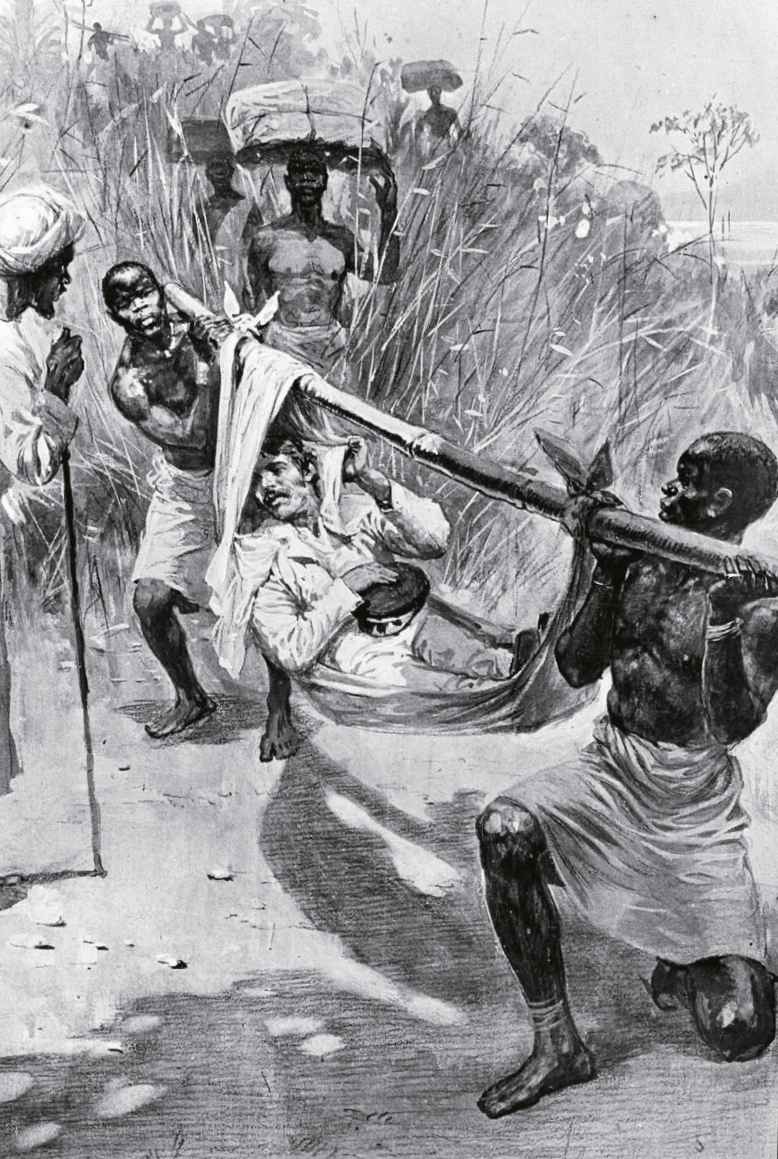

In March 1866, Livingstone led an expedition team, which, except for himself, was composed of African indigenous people. Unfortunately, due to the slave trade that Livingstone strongly opposed, the road was full of desolate scenes. Most of the once prosperous villages became uninhabited areas, which also brought great difficulties to the expedition team’s food supply. Livingstone wrote in a letter: "Food was scarce along the way, and I could only exchange my best clothes for a little ordinary food. I traveled hard throughout the journey, and except for occasionally hunting a pheasant or guinea fowl, there was no meat supplement." Despite this, the expedition led by Livingstone still arrived at the southern end of Lake Tanganyika in April 1867. He also went west twice to explore Lake Mweru, which had rarely been explored. Years of exploration life had caused him to contract tropical malaria many times. At this time, his body was already weak and thin like a piece of dry firewood. Most of the time, he had to be carried on a stretcher. Despite this, he still insisted on the investigation and discovered Lake Bangweulu southwest of Lake Tanganyika. In addition, he also discovered the Zanaraba River, which flows north and passes through a series of lakes. However, he did not know at the time which river system this river belonged to-was it the Nile River system or the Congo River system? He no longer had the strength to solve this problem because his health was getting worse and worse. Livingstone had to return eastward, cross Lake Tanganyika, and temporarily stay in the village of Ujiji on the east shore of the lake to treat his illness and recuperate. It was already 1871.

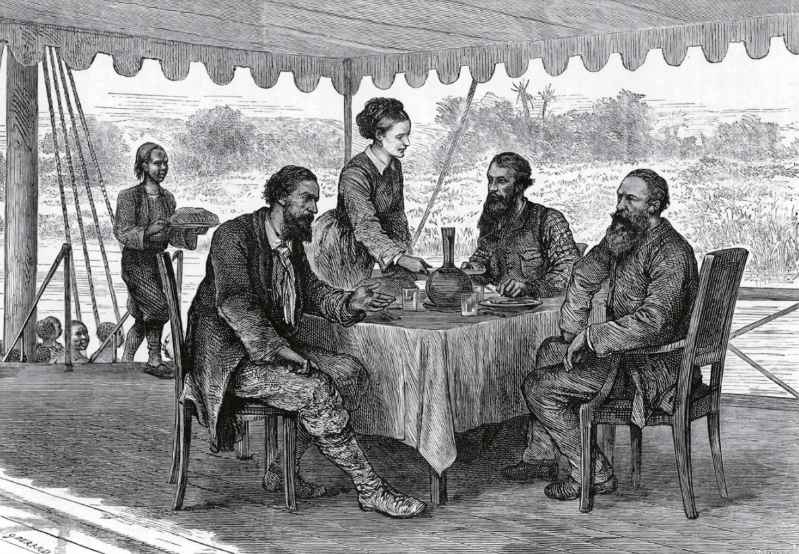

At this time, a very dramatic scene occurred. Henry Moulton Stanley (born in Britain, 1841-1904), a reporter for the New York Herald, suddenly came to Livingstone. It turned out that this widely circulated newspaper had not received any news about Livingstone for three years, and many readers wanted to know the explorer’s recent situation, so they wrote in and asked. So the newspaper sent Stanley, a young and famous reporter, to Africa to find Livingstone and make exclusive news reports in a timely manner. In February 1871, Stanley organized a team of 157 people, carrying a large amount of goods, and headed inland from the coast of Africa. On November 10, he arrived in Ujiji and finally found Livingstone. "Thank God, I can meet you here!" This meeting between the two was later called "the most famous meeting in the history of exploration." Despite being seriously ill, Livingstone still insisted on exploring the northern end of Lake Tanganyika in 1872. He was sure that no river flowed out from the north bank of the lake, so the lake could not be considered the source of the Nile. A theory about the source of the Nile was shattered. Unwilling to give up, Livingstone went to the Lualaba River again the following year. On the morning of May 1, 1873, his servant walked into his room and found him kneeling beside the bed, and his body was already cold. His loyal black companions could not bear to bury him in the wilderness of Africa. They put his body on a stretcher and carried it to the coast of the Indian Ocean, a journey of nearly 1,500 kilometers.

Livingstone’s body was finally transported back to London, England, and buried in the famous Westminster Abbey. His unfinished ambition to find the source of the Nile will be completed by Henry Stanley.

Crossing the Dark Continent

After the legendary encounter in Ujiji Village, Stanley stayed with Livingstone for 4 months. Although it was only a short 4 months, Livingstone’s personality charm had completely conquered the young man in front of him. In Stanley’s view, Livingstone was a saint, an apostle of Christ, and a perfect man with endless tolerance and self-sacrifice. Stanley was an admirer of Livingstone throughout his life. When he learned that his hero had passed away, he was shocked: "I hope I can inherit his will, the bright light of Christianity, and choose me to explore the African continent!" You know, Stanley originally had no good feelings towards the African continent. I hate this place from the bottom of my heart," he wrote in his diary, "Except for one or two days of taking quinine, I rarely stay healthy.

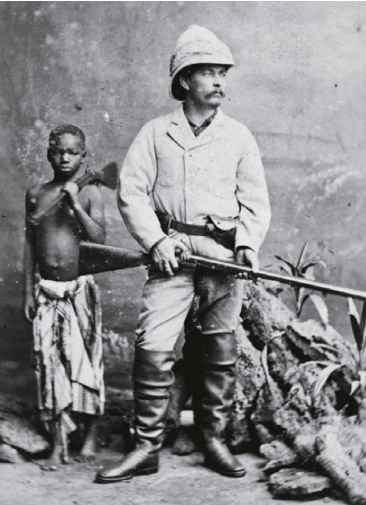

In 1874, Stanley officially announced to the outside world that he would organize an expedition to Africa with the goal of finally solving the problem of the source of the Nile River and exploring the entire process of the Congo River. Stanley’s fundraising activities went very smoothly due to the fame he gained from his meeting with Livingstone. Soon, he came to Zanzibar and began to organize his expedition, including 353 African native porters and soldiers, and 3 European whites. The most important equipment of this expedition was a disassembled ship so that it could be transported to Lake Victoria and from one river section to another (or lake) in the future. This work required a large number of porters, which was why so many native porters were recruited.

Stanley and his large team set out on the African continent on November 17, 1874, and then headed northwest. Disease and hunger took many lives. In January 1875, Stanley had lost 1/4 of his followers. But in the next month (February 17), the expedition finally successfully reached the southern shore of Lake Victoria.

Since people at that time already knew that the terrain of Lake Victoria was higher than Lake Ehuat discovered by the Bakers. After all, water flows to lower places, so Stanley did not choose to waste time going to the "second source" behind first, but went straight to investigate Lake Victoria. Stanley spent 2 months sailing around the lake shore and accurately determined the outline of the lake. His investigation results confirmed Speke’s inference-the Nile did originate from Lake Victoria. Stanley went a step further and confirmed that the main tributary of this great lake was the Kagera River, which was the most distant source of the Nile River, thus finally solving the source problem of the Nile River. In addition, near the equator west of Lake Victoria, he discovered the snow-covered Rwenzori Mountains, whose main peak is 5,119 meters high, the third highest peak in Africa. Next, Stan and the expedition team went south to Lake Tanganyika and confirmed that the watersheds between the Nile River, the Congo River and another large river, the Zambezi River, were very close to each other. The Lualaba River, which Livingstone had high hopes for, was indeed not the source of the Nile River, but belonged to the Congo River system. After that, Stanley began his expedition to the Congo River. Until the morning of August 9, 1877, the expedition team finally reached the mouth of the Congo River (Port Stanley). From the day they left Zanzibar Island, the trip took a total of 999 days. Later, Stanley wrote a book about his adventure experience, titled "Across the Dark Continent".

A mystery that had lasted for thousands of years was finally solved. Henry Stanley completed the relay race that had been passed down by Richard Burton, John Speke, the Bakers, and Livingstone, revealing the true face of the upper Nile River system and finding the source of this great river. As Stanley proudly wrote, "I am sure that there is only one place in Lake Victoria where the Nile flows out, and that place is the Ripon Falls."