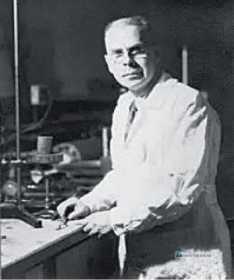

Slotin was buried in his hometown of Winnipeg

After Louis Slotin died, his parents Israel and Sonya Slotin flew back to their hometown in Canada from Santa Fe, New Mexico, USA, with Slotin’s coffin on board, which was engraved with the words "Home of the Hero’s Body".

Since the Slotin family was Jewish, the US military arranged for the plane to arrive in Winnipeg, Canada before sunset on Friday (the beginning of the Jewish Sabbath). The funeral was held on the afternoon of June 2, 1946 (Sunday), and nearly 3,000 people attended the funeral. Rabbi S. Frank described Louis as "one of the most outstanding scholars this city has ever had", and he also quoted the evaluation of Major General Groves, the main person in charge of the "Manhattan Project", "His brave and quick actions saved the lives of seven colleagues"

Memorial

After Slotin’s death, people expressed their condolences. On June 14, 1946, the Los Alamos Times published a poem by deputy editor Thomas P. Ashlock, "Slotin - A Tribute", in recognition of his noble quality of sacrificing himself to save others in times of crisis.

At that time, the official announcement said that Slotin, who quickly moved to the upper hemisphere, was a hero who interrupted the critical reaction and protected the other seven observers in the room: "Dr. Slotin, regardless of his own life and death, his quick response prevented the experiment from developing to a more serious level. If it had not been stopped, it is certain that the experiment would have resulted in the death of all seven people working with him and serious injuries to nearby personnel."

In 1948, at the University of Chicago, Slotin’s colleagues at Los Alamos and the University of Chicago jointly initiated the establishment of the "Louis A. Slotin Memorial Fund". Prominent scientists such as Robert Oppenheimer, Jr., the scientific director of the Manhattan Project, and Nobel laureates Luis W. Alvarez and Hans A. Bethe delivered 15 lectures at the university. These memorial lectures continued until 1962, when the funding ran out.

However, there have always been different voices about Slotin and this dangerous nuclear accident. In September 1946, in response to a request for donations to the fund, Robert B. Broad, a senior physicist who had worked on the Manhattan Project and a professor of physics at Berkeley, wrote a thought-provoking letter to his colleague Professor Samuel K. Allison at the University of Chicago: "Enclosed is a small donation for your memorial fund for Louis Slotin. The exact details of how he was harmed by radiation are not easy to obtain for those physicists who work in engineering fields rather than pure physics. However, I have learned from the comments of others who have been here that the accident was completely avoidable and that Slotin did not use the formal procedures and therefore killed himself. himself and others in the lab. I gather from the comments I have heard about the Slotin incident that he himself was guilty of negligence and that automatic safeguards were largely absent because Slotin insisted that they were not needed. I believe that a prize given annually to a person who has made an outstanding contribution to the safety of handling hazardous radioactive materials or recognition of successful accident-free projects would do more good. By publicizing some outstanding idea or successful research project in the process of using hazardous materials, it would certainly help to reduce the type of accidents like the one that killed Slotin. "

There is no doubt that Louis Slotin died a hero. Louis Slotin’s story has been told in various forms. For example, in the 1955 novel "The Accident" by Desta Mastas: the 1989 Hollywood movie "Fat Man and Little Boy": the writer Paul Mullin wrote a play called "Louis Slotin Sotana". In addition, an asteroid discovered in 1995 was officially named "12423 Slotin" in 2002.

The end of the "Demon Core"

The "Demon Core" was originally called "Rufus". After the Daghlian and Slotin accidents, people called it the "Demon Core". But after all that happened, this abandoned nuclear weapon also reached its end.

After the Slotin accident, the radioactivity of this plutonium core continued to increase. The military used it for the first post-war nuclear explosion test-"Crossroads Operation" conducted at Bikini Atoll, which was scheduled for one month after the accident. "Crossroads Operation" was a nuclear test conducted by the United States at Bikini Atoll in 1946, and it was also the fourth and fifth use of nuclear bombs in the history of the United States.

On July 1, 1946, the Gilda nuclear bomb made of the "Demon Core" was detonated with an explosion equivalent to 23,000 tons of TNT, ending its life.

The birth of the "Demon Core" has left a heavy mark in the history of physics and even in the history of mankind. In the development of atomic energy, since 1945, similar critical accidents have occurred 60 times, resulting in the deaths of at least 21 people, and the "Demon Core" is the most powerful and far-reaching one. The only thing to be thankful for is that the experimenters in these two accidents reacted quickly and were able to endure the instantaneous heat and severe pain to overturn the reflector. Otherwise, if the nuclear reaction continues to amplify, the death list of the "Demon Core" may be much longer.

After this

At the time of the accident, there were four physicists, a student, an engineer, a photographer and a guard watching the experiment. Because Slotin’s body blocked most of the radiation, they barely escaped. On May 25, 1946, four of the remaining seven people in the laboratory were discharged from the hospital. The remaining three were Alvin Graves, Stanley Crane and Dwight Smith Young.

Subsequent studies showed that three of the seven survivors of the Omega Laboratory accident died several years later from complications that may have been caused by radiation. Clifford Hornik believes that "the U.S. government’s response to that tragedy established a pattern of secrecy that continues to this day." In 1993, Roger Mead, the official archivist and historian of Los Alamos Laboratory, revealed in a telephone interview: "In that period, everything was confidential, but when people asked for things, we would let them declassify. For many years, the accident affected people’s lives, and no one was really interested in telling the story. Physicists tried to piece their lives back together. People thought that this incident was covered up, but it was not the case.

Graves was the person closest to Slotin at the time of the accident. At the age of 34, he was also severely exposed to 360 rems of radiation, but after several weeks of treatment, he survived. At the age of 56, Graves died of a myocardial infarction. He suffered from neurological and eye diseases caused by radiation all his life.

Dwight Smith Young, a photographer who was present at the accident, was also exposed to radiation, but recovered and was discharged from the hospital. 27 years later, he died of aplastic anemia.

Student Klein changed his career to become a lawyer after the accident and died of an unrelated disease in 2001. He refused to participate in any accident investigation and research before his death, so there is no data.

Among those who were discharged early, Marion Edward Cieslicki died of leukemia 19 years after the accident at the age of 42.

The guard who ran away, Private Patrick J. Cleary, died in 1952 1989-1990, died in the Korean War.

Several other physicists and engineers were more fortunate and lived longer.

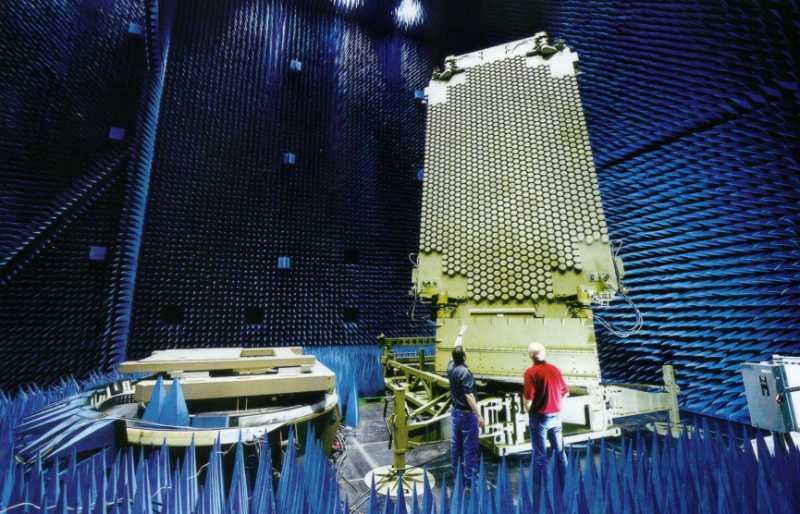

No conclusion has been drawn as to how much their deaths were related to the accident, but no research has denied it. With two fatal accidents just a few months apart, Los Alamos National Laboratory finally decided to take some action to stop the "devil’s rampage." The newly formulated operating procedures meant the end of "hands-on" critical experiments. To avoid similar accidents, the United States ordered that all plutonium core experiments must use robotic arms and that experimenters must keep a certain distance from the plutonium core. Los Alamos Laboratory immediately began work on a remote control system, with the critical test equipment and operators about 1/4 mile apart. There have been no more fatal casualties since then.

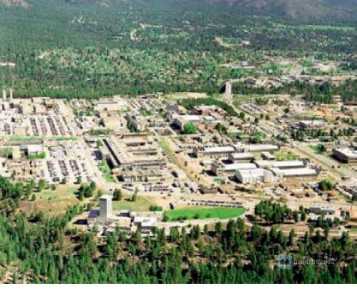

Today, the ultra-modern Los Alamos Laboratory has about 7,800 employees and covers more than 43 square miles. The laboratory’s researchers spend less than 50% of their time on weapons research. Part of the original Pajarito Canyon Laboratory, where the accident occurred, is still in operation.

Some explanations

Blue glow

Many criticality accidents are accompanied by a blue glow that can instantly heat surrounding objects. The blue glow of a criticality accident is the spectrum emitted when ionized excited atoms (or molecules) in the air return to a non-excited state, mainly produced by oxygen and nitrogen. As a result, electric sparks and even pale blue lightning will be generated in the air.

Exothermic

Some people who have experienced criticality accidents report feeling "a wave of heat." However, it is still unclear whether this is a psychological reaction to the horror that just happened, or a real physical thermal effect caused by the large amount of energy released in the accident (or a non-thermal energy signal that triggered the heat receptors in the skin). For example, when Louis Slotin’s accident happened, about 3x1015 fissions occurred, which only produced energy to increase the skin temperature by a few hundredths of a degree. But the energy accumulated in the plutonium ball at that time was about 80 kilojoules, which was enough to raise the temperature of a 6.2 kg plutonium ball by about 100°C (the specific heat of plutonium is about 0.13]·g·1/K). The heat radiation of the metal is enough to make people nearby feel the temperature rise. This explanation lacks to explain the feelings of the victims of criticality accidents, because people who were several feet away from the plutonium ball also felt the heat. It is also possible that the ionization damage and free radical formation caused by ionizing radiation at the cellular level damaged the tissue and caused people to feel the burning sensation.

Another possible explanation is that the phenomenon of heat generation was inferred after the observation of the blue glow. A witness report of all criticality accidents showed that heat radiation was only present when the blue glow was present. This may suggest that there is a connection between the two phenomena, and one of them can be observed immediately. After collecting and analyzing the radiation from nitrogen and oxygen atoms in the denser (non-ionized) surrounding air, it was found that about 30% of the radiation was in the ultraviolet band and about 45% was in the infrared band. Since the skin can feel infrared light as heat, and ultraviolet light can cause sunburn, this may explain the heat wave felt by the witnesses. (To be continued)