On October 26, 1888, on the steep shore of the sacred and beautiful Issyk-Kul Lake, "the lost pearl of God", the solemn and dignified priest finished his prayers, and the Cossacks and soldiers with sad faces slowly filled the newly dug grave with soil, burying with their own hands this closest companion who "died before achieving his goal". On a mountain-shaped rock monument built by the order of Tsar Alexander III, there is a bronze medal cast by the Russian Royal Academy of Sciences, with a portrait of the deceased engraved on it. The name of the deceased, "Nikolai Mikhailovich Przevalsky" and the date of birth and death are engraved on the top stone. Below the portrait is the inscription on the back of the medal. The Russian scientific community uses the simplest words to give the most accurate summary of his lifelong scientific career: "Awarded to the first explorer of Central Asian nature."

Young Hunter

Przevalsky’s ancestors were Zaporozhian people, Russian Cossacks living in Ukraine, that is, the protagonist depicted in the famous 19th-century Russian critical realist painter Repin’s famous painting "Zaporozhian Letter to the Sultan". His ancestors served as officers in Poland, and because of their heroic military exploits, they were awarded the title of nobility and became the owner of 5 villages, completing the original accumulation of family wealth. The following experience was like many ups and downs in the story of family decline. When Przhevalsky was born in 1839, his father was just a retired soldier who owned a small farm in Smolensk. God seemed to deliberately make things difficult for this not-so-rich family. When Przhevalsky was 7 years old, his father passed away due to illness, and his mother took on the responsibility of raising and educating two children alone. Although they lived in poverty, the young men who "did not know the taste of sorrow" still had their own happiness. The dense forests around the manor became a natural playground for the two brothers. Przewalski was either very patient and quietly catching small beetles on the trees, or shouting and chasing flying butterflies, or lying quietly on the ground listening to the melodious birdsong. The mysterious and colorful nature brought him endless happiness in his childhood and left a deep impression in his heart.

Like other children of manor owners, Przevalsky started family education at the age of four or five. He completed his initial enlightenment with his uncle and nanny, and learned to recognize Russian and French, the latter of which was a necessary skill for Russian nobles and wealthy families to reflect their upbringing and status. In 1849, they left their mother and went to Smolensk Middle School to receive formal school education.

Although school life made Przevalsky feel fulfilled, it was not what he longed for in his heart. As long as he had time, he would try his best to escape from school to the fields and forests outside Smolensk and throw himself into the embrace of nature. Only "when appreciating nature, there is indeed a special and infinitely deep feeling." Every holiday, he would rush back to his hometown, take the hunting rifle left by his father and follow his uncle into the forest to hunt, adding some delicious game to the table almost every day.

From the time he first picked up a hunting rifle at the age of 12 and killed a fox, his racial talent of "fighting nation" was completely stimulated by the wonderful and infinite nature, and he quickly grew into an excellent hunter with keen observation and full of energy, "quiet as a virgin, moving like a rabbit". He was so obsessed with hunting that he would strip naked and swim across the river in early spring when the cold wind had not yet retreated in order to chase prey. The tempering of his youth made him increasingly disgusted with the city wrapped in steel and concrete, and he grew into a loyal worshiper of nature, which seemed to foreshadow the direction of his future life.

The idol changed from a war hero to a geographer

Like his ancestors, Przewalski’s father and grandfather had people join the army, which became an unwritten tradition. But for the future explorer, his motivation to enter the military camp was not only the glory of his ancestors, but also the inspiration of the heroes of the "Battle of Sevastopol". After graduating from high school at the age of 16, he couldn’t wait to put on a military uniform. In 5 years, Przewalski was promoted from an ordinary sergeant to a warrant officer, but the boring military life and poor diet completely shattered his dream of fighting in wars. In his spare time, he either went out hunting or read in the dormitory, especially interested in history and travel notes. The knowledge of zoology and botany in middle school also came in handy, making him interested in plant collection, and he began to consider getting rid of this lifeless life. The wheel of fate began to turn slowly towards the set goal. In his heart, a lingering idea gradually emerged, that is, no longer drifting in the army, but to be a free traveler. He even had a sudden idea to report to his superiors and asked to be transferred to the distant Amur State for service, but the answer he got was three days of confinement.

After careful consideration, Przevalsky applied for the military academy and went to study at the Nikolayev Academy of the General Staff in St. Petersburg. His tall and strong physique and vigorous appearance left a good initial impression, but he was not so easy to get along with in actual contact. Przevalsky always kept to himself, did not get close to others, and was unwilling to even join the study group. This was not because he was withdrawn, but because he was short of money. When he first arrived in St. Petersburg, he was penniless and often could not even have lunch. In his daily studies, he listened carefully and performed well in subjects such as geodesy, but he had no interest in military subjects. After being influenced by a large number of geographical works, his idol changed from a war hero to the famous German geographer and naturalist Alexander von Humboldt, whose lifelong adventurous spirit and three-volume "Central Asia" made him yearn for the vast hinterland of Asia and established his ambition to travel to the distant East.

During this period, Przevalsky’s exploration career made another progress, that is, he found the "organization" he worked for - the Russian Imperial Geographical Society. The society was established in 1845 with the purpose of meeting scientific needs and also providing assistance to the Tsar’s political needs for external expansion. The leader of the society was the geographer Semenov, who was given the title of "Tienshanski" by the Tsar. He was also deeply influenced by Humboldt and went deep into the Tianshan Mountains in the Issyk-Kul area of my country from 1856 to 1857 to conduct geographical surveys.

I can’t always take my wife out for adventures

In 1866, Przevalsky was transferred to the Russian General Staff and was sent to the East Siberian Military District as he wished. When he passed by St. Petersburg, he visited Semenov and eagerly recommended himself to lead the expedition team to Central Asia. Semenov was moved by this somewhat reckless officer, but he could not hand over the expedition team to an inexperienced "greenhorn". He needed a "letter of surrender" - to complete a valuable investigation in the Ussuri River area.

Prior to this, Przewalski had already prepared for the expedition with great excitement and recruited a German specimen collector. This young man fell in love with a beautiful Russian girl before leaving Warsaw. He went to Siberia, but his heart stayed in Warsaw. He was deeply trapped in the pain of missing her. He was trapped by love every day, sighing and even crying, and unable to work. Przewalski had no choice but to send him back to his beloved girl. This incident had a profound impact on his view of marriage. He rarely communicated with women. After he was determined to devote himself to the investigation, he decided not to marry for the rest of his life for his ideal. In his opinion, "My profession does not allow me to get married. If I go out for an expedition, my wife will cry. I can’t take my wife with me on an expedition... I will live with my veterans, who are as loyal to me as my legal wife." After him, many world-famous Central Asian explorers also chose to remain single. The Swede Sven Hedin even said: The vast hinterland of Asia is his eternal bride. He has "married" China.

In 1867, the Siberian branch of the Russian Imperial Geographical Society ordered Przhevsky to lead an expedition team to the Ussuri River Basin as soon as possible. The main purpose was to collect military intelligence and draw a route map for the 400,000 square kilometers of Chinese territory east of the Ussuri River occupied by Russia after the signing of the Sino-Russian Beijing Treaty. To serve the further invasion of China. At the same time, he also carried out some scientific investigation activities, such as clarifying the distribution of animals and plants in the investigation area and collecting specimens. In May, Przhevalsky led an expedition team from Irkutsk and arrived at Khabarovka at the mouth of the Ussuri River after a month. They then went upstream along the Ussuri River, conducted military reconnaissance, plant surveys and casual hunting along the way. They surveyed Lake Khanka for three weeks, resting for five hours a day. They collected more than 600 animal and plant specimens and finally arrived at the end of the survey - the source of the Ussuri River - on the day before New Year 1968.

One gun against two bears

After the expedition team finished its work, Przewalski was not in a hurry to leave, but made his own plan - to welcome the arrival of spring in Lake Khanka and observe the migration of birds, because at that time no natural scientist knew what spring was like here and what the bird population was like. It was not until October that he ended this small trial expedition. The cranes and black bears made him feel the wonders of the world. In the Khanka Lake area, he saw an unforgettable scene. Millions of birds of all kinds flew from the far south, covering the sky like locusts, and then landed in the Khanka Lake to roost and feed. Przewalski was so excited that he wrote to his uncle in a distant place: "I can’t even imagine it in my dreams. There are all kinds of ducks and birds in Lake Khanka. Some birds are so beautiful that even artists may find it difficult to draw them. Now I have 210 bird specimens here. Among them is a crane, which is all white, with only two wings half black. When the crane spreads its wings, it is eight feet long. When I found it in the bushes, I was shocked by its beauty." However, what happened next was shocking. He did not preserve this beauty, but raised his hunting rifle. The crane fell to the ground like a "bundle of grass", but he was "excited like a child".

The chilling experience during the inspection in Suchang made Przewalski unlock the "primitive power" in the body of the "fighting nation" for the first time, and feel the danger and impermanence of nature. One day, he encountered two bears alone in the forest, and he only had a double-barreled hunting rifle in his hand. The fearless hunter had no intention of retreating. Instead, he raised his hunting rifle and aimed at one of the bears, wounding it with the first shot. The two bears fled into the bushes, and Przewalski chased them with his rifle. Unexpectedly, the big bear also came back. During the chase, the injured bear turned around and opened its mouth to attack. He waited for it to get close and then shot it between the eyes and ears, and the big bear fell down. Seeing this, the other one also pounced on him, and he quickly climbed up a birch tree to hide. The big bear walked around the tree for a few circles, looked back at its dead companion, and turned away. He quickly loaded the bullet, jumped down the tree, chased it, and then shot it dead with one shot. After a fierce battle, it was already dark, and Przewalski had to abandon the prey and wait until the next day to find someone to transport it back. As a trophy worth showing off, he handed over a skull to the St. Petersburg Academy of Sciences.

Przhevalsky showed his talent in the Ussuri River survey and left the first archive of the history, geography and folk customs of the Ussuri River and Xingkai Lake area for the Russian Imperial Geographical Society. When he returned to St. Petersburg after a long absence, the Russian Academy of Sciences, the Royal Geographical Society and other academic institutions held many reports for the heroes who returned with honors. At the venue, Przhevalsky, who became famous in one battle, was in high spirits and his impassioned speech aroused warm welcome from the audience. When talking about bird surveys, he imitated the calls of various birds vividly, making the audience laugh happily from time to time. His report became the most authoritative scientific report on the Ussuri River area in the European academic community at that time, which attracted great attention from various countries. The Russian Imperial Geographical Society also awarded him a silver medal. This was his first scientific survey medal, which also marked that he had entered the Russian geographical community and had a place.

The whole camp is like a slaughterhouse

Europeans have long been interested in Central Asia and Northwest China. One reason is that there are still many blanks on the map waiting to be filled in this area. The other reason is that it is located on the Silk Road connecting the East and the West. Russians have been traveling here since the 16th century. With the rise of modern Central Asian exploration, the "Great Game" between the two major colonial powers of Britain and Russia made this region a "paradise" for explorers to compete with. Putting aside political factors, the vast land of northwest China contains extremely rich resources. It is a place where scholars engaged in geography, natural history, history, anthropology and other disciplines can become famous. The Russian Imperial Geographical Society is naturally ambitious.

In 1870, the Russian Imperial Geographical Society officially handed over the Central Asian exploration, a task with multiple values such as political, military and scientific research, to the new explorer Przhevalsky. With the approval of Tsar Alexander II, Przhevalsky’s first trip to northwest China was mainly aimed at Inner Mongolia, Gansu and Qinghai. Ordos and Qinghai, which had not yet been scientifically explored, were the perfect places for him to become famous.

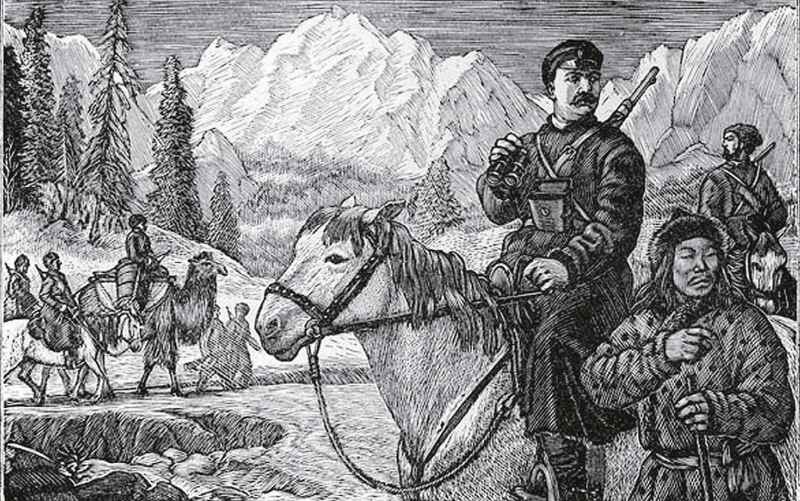

1870 In November, Przevalsky, along with his assistant and two Cossacks, set out from Kyakhta, an important border town between China and Russia, and traveled 1,600 kilometers along the then important trade route, arriving in Beijing via Kulun and Zhangjiakou. After arriving in Zhangjiakou, the expedition team finally got rid of the more than 1,000 kilometers of Gobi Desert and the harassment of crows that snatched food all the way, and headed for the Forbidden City, the heart of the Eastern Empire, along the world-famous Great Wall. The heavily fortified city walls and tall and majestic buildings strongly attracted him, but an experience in the city turned this admiration into deep anger. All the gates in the city were closed, and everyone showed strong hostility without concealing it. There were almost no hotels for them to stay. "People here call Europeans ’devils’ in front of their faces and behind their backs." Faced with the hostile attitude of the capital, this European with colonialist ideas deeply rooted in his bones said viciously: "Probably only European guns and cannons can do a little business here. In order to deal with the dangers that will be faced next, he replaced most of his equipment with weapons and hunting tools, which can almost arm a small army.

At the end of February 1871, Przevalsky and his four-member team and his faithful hound "Faust" set out from Beijing to conduct natural history surveys in Duolun Nor and Dari Lake in the north, then went west around Hohhot, along the Daqing Mountains to Baotou, crossed the Yellow River to Ordos, and then investigated along the Yellow River Valley. After days of arduous journeys in the Gobi Desert, he saw for the first time the winding and turbulent Yellow River heading into the Loess Plateau. Although Przevalsky tried to contact the locals, he still could not change their hostile attitude towards foreign "devils". They neither sold food to them nor were willing to lead the way for him. He had to familiarize himself with the terrain and get enough food by hunting. The entire camp was like a slaughterhouse, and each member of the expedition team became a butcher.

Although the beauty of Ordos was so attractive, Przevalski had to continue westward to the Alashan region. In Dingyuanying, he was warmly received by the Prince of Alashan. The courtesy and hospitality of this prince, who was pale due to long-term opium smoking, made him feel cordial and warm. His followers took the opportunity to start a small business in the city, selling the bronze mirrors, necklaces, pocket knives, and soaps purchased in Beijing to the locals. The goods sold at several times the price made him earn a lot of money. As the funds were about to run out, the passports issued by the Qing government could only reach the border of Gansu. The Qinghai that Przevalski had been thinking about was still more than 600 kilometers away. The expedition team had to go back home and return to Beijing to raise funds and apply for passports again.

Waves between Lhasa and Lop Nur

In Beijing, in appreciation of Przevalski’s unprecedented contribution to Russia’s new Central Asian exploration data, General Frangli of the Russian Legation in Beijing assisted him in obtaining a large amount of exploration loans and obtained travel passports to Gansu, Qinghai and Tibet from the Qing government. He was able to go to Qinghai Lake and the holy city of Lhasa that he had longed for. After returning to Alxa, he visited the Prince of Alxa again and persuaded a Tibetan caravan from Qinghai to agree to travel with them. Following the caravan, Przevalski went from Dingyuanying through Gansu, crossed the Qilian Mountains, crossed the Datong River, passed by Tiantang Temple, and arrived at Quezang Temple, more than 60 kilometers away from Xining Prefecture, and obtained many animal and plant specimens along the way. During his stay in Quezang, he developed a strong interest in rhubarb, a Chinese medicinal herb with a long history and wide application, and obtained a batch of seeds to take back to Russia for sowing. This is one of the most in-demand Chinese commodities on the Silk Road for thousands of years.

In October 1872, Przevalsky and his party traveled along the ancient road to Lhasa and soon arrived at his previous destination - the mirror of the plateau, Qinghai Lake. He stood by the Qinghai Lake in ecstasy and couldn’t help shouting: "My lifelong dream! Come true!" After enjoying the beautiful lakes and mountains and listening to the legends about Qinghai Lake, Przevalsky turned to the main task of the lake area investigation - catching wild donkeys. Here, he met the Tibetan envoy who was sent by the Dalai Lama to Beijing to meet Emperor Tongzhi in 1862. The latter told him that if he could go to Lhasa, he would definitely receive the highest level of hospitality from the Dalai Lama, which ignited his infinite yearning for Lhasa. The limited funds of the expedition team once again extinguished the flame in his heart. The expedition team did not immediately go to Tibet, but walked along the northern shore of Qinghai Lake into the Qaidam Basin, but the two goals of Lhasa and Lop Nur always wavered in his mind.

Przevalski tried to cross the Tanggula Mountains to Tibet. Along the way, local Mongolians often told him about the route to Lop Nor and the wild camels and horses that appeared and disappeared in the wilderness, which left a deep impression on him. After entering the northern Tibet region, he was overwhelmed by the countless wild yaks, blue sheep, wild donkeys, antelopes, bears, rabbits, foxes and wolves in the desert. Some animals were in groups of thousands. Such rich animal resources made Przevalski, who loved hunting, indulge in his addiction. Sometimes he could hunt nearly a hundred animals at a time, which could feed a hundred people for a whole winter. Food was inexhaustible, but it was troublesome to eat the fresh meat on the ground. The severe winter made the meat frozen hard, and it was an extremely long process to thaw it and cook it into soup. The hungry team members could only have lunch at seven or eight o’clock in the evening. The severe winter in the northern Tibet region made the expedition team move very slowly. In the New Year of 1873, exhausted and out of ammunition and food, Przevalsky reached the Bayankala Mountains, about 850 kilometers from Lhasa. He had no strength to move forward and had to turn back along the same route. Przevalsky’s first expedition lasted three years and traveled 12,000 kilometers. The tens of thousands of animal and plant collections he brought back showed the rich species resources in the vast land of northwest China, which caused a sensation in the entire European academic community. After returning to Russia, he recorded his experience of the expedition and wrote a book "Mongolia and Tangut Region", which was a best-seller.

Disputes about the location of Lop Nur

In 1876, Tsar Alexander II ordered Przevalsky to form the second Central Asian expedition team, planning to survey the eastern part of the Tianshan Mountains, the Tarim Basin, and the Lop Nur area, and then go to Lhasa from the southern edge of the Tarim Basin, and survey the source of the Yarlung Zangbo River, and then cross the Himalayas to the Irrawaddy River and the Salween River to return. This expedition attracted great attention from the Russian government, military and academic circles, especially the trip to Lhasa, which was highly praised by the Russian Ministry of Foreign Affairs. This also fully exposed Russia’s covetousness for China’s northwest and Tibet.

In this year, Xinjiang was in the midst of the turbulent times when Yakub Beg was stirring up rebellion and Zuo Zongtang entered Xinjiang to quell the rebellion. Przhevalsky crossed the Tianshan Mountains, entered the hinterland of Xinjiang along the Ili River Valley, and later arrived at the area occupied by the Yakub Beg rebellion. Since Yakub Beg’s army prohibited them from going to Karashar, the expedition team decided to go from Korla to Lop Nur. In the forests in the upper reaches of the Tarim River, Przhevalsky and others discovered traces of Xinjiang tigers and were the first to make them public. After that, countless Western explorers and local hunters began to enter the Tarim River basin to hunt Xinjiang tigers. With the deterioration of the environment and human hunting, the number of Xinjiang tigers decreased rapidly, and a hundred years later, they were officially declared extinct at an international conference held in India.

In the spring of 1877, Przewalski, as the first European explorer to enter Lop Nur, completed a "major geographical discovery" after several months of investigation, and determined the geographical location of Lop Nur to be 39 degrees 31 minutes 2 seconds north latitude and 83 degrees east longitude. This "discovery" was 1 degree south of latitude and 1 degree east of longitude compared to the Qing government’s actual survey map, which caused a great shock in the European academic community and also caused a century-long debate about the location of Lop Nur. The opposing party was led by Ferdinand von Richthofen, the chairman of the Berlin Geographical Society of Germany and the inventor of the "Silk Road", who believed that the location of the Qing government’s actual survey map was correct and that Przewalski’s discovery was not Lop Nur at all. After that, the European geography and exploration communities took sides and supported one of the parties. Sven Hedin, a disciple of Ferdinand von Richthofen, even went to Lop Nur for three surveys to cheer for his teacher. Later, Chinese and foreign scholars proved that what Przhevalsky "discovered" was not Lop Nur at all, but Karaheshun Lake, the second largest lake in the Lop Nur area.

After the investigation of Lop Nor, the expedition team returned to Yining via Korla, and then set out again to Lhasa, the final destination of this investigation. While the team was on the march, Przewalski received the news of his mother’s death a few months ago from a telegram sent by his brother. Such a painful blow quickly broke him down. Coupled with the troubles of injuries and the deterioration of Sino-Russian relations, the second investigation was hastily ended halfway through.

Named Przewalski’s wild horse

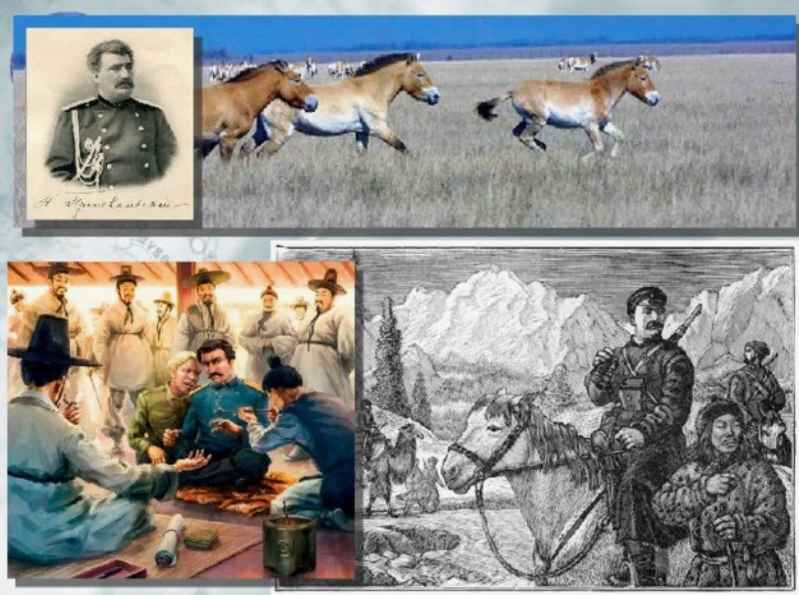

Entering Tibet and Lhasa was Przewalski’s most desired goal since his investigation in Central Asia. Since the first and second investigations did not achieve the goal, he directly called it the "first Tibet investigation" when he formulated the third Central Asian investigation plan in 1879. In the spring of 1879, a 14-member expedition team set out from Zaisan, Russia, crossed the Altai Mountains, passed through the Junggar Basin, passed through Qitai, Hami, Turpan, Shazhou, crossed the Qilian South Mountains and entered the Qaidam Basin. In the Junggar Basin, Przewalski captured an unruly wild horse. When he returned to Europe with the specimen, it once again caused a sensation. The wild horse he captured was the last wild horse in the world with a 60 million-year evolutionary history. It was also the only horse species that retained the original genes. It was of extraordinary biological significance. The European academic community named it the Przewalski wild horse in memory of Przewalski’s contribution. But for wild horses, being world-famous is definitely not a good thing. This species that originally ran freely on the grassland and reproduced for tens of thousands of years would never have thought that the person who named them would bring them a catastrophe.

After Przewalski, countless European poachers followed. These poachers who claim to be "civilized people" choose the spring when wild horses give birth, and they take turns to use domestic horses to hunt them. In less than 50 years, the wild horses that were originally scattered throughout the Junggar Basin have become precious endangered species and are facing the risk of extinction.

On September 12, Przevalsky set out to enter the Qinghai-Tibet Plateau and collected animal specimens along the way. When they reached the Danglaling Pass in the Tanggula Mountains, the expedition team had a serious conflict with the Tibetan Yegolai tribe, killing and injuring many Tibetan compatriots, and forcibly crossed the pass into Tibet. The evil deeds of Przevalsky and others caused great indignation among the surrounding Tibetan tribes and panic among the Tibetan local government, which ordered heavy troops to be stationed on the line from the Tanggula Pass to Nagqu and prohibited Tibetans from contacting the expedition team. When the expedition team arrived in Nagqu County, officials who came from Lhasa clearly told him that they were prohibited from going to Lhasa. Faced with the hostility of the entire Tibet, the arrogant Przevalsky could only order the expedition team to turn back in frustration. Lhasa was within reach, yet so far away that it became the most distant dream of his life.

With the fruitful results of the first three expeditions as a foundation, it was natural for Przevalsky’s fourth expedition to be approved by the Tsar and the Russian Imperial Geographical Society. The scale of the expedition team was slightly larger than before, and a volunteer was added - his fellow villager Kozlov - this proud student later became famous throughout the world for discovering the ruins of the ancient Xixia city of Heishui City and collecting thousands of cultural relics. Although Przevalsky gave up his plan to go to Lhasa, the unknown northern Tibet and the source of the Yellow River were still worthy of exploration. After several months of travel, the expedition team arrived at the Oduntala Basin, the source of the Yellow River, in mid-May 1884. Standing at the source of the Yellow River and looking at the turbulent water, the complacent Przevalsky claimed to be the first person to reach the source of the Yellow River, and wrote a note in his diary and survey report. Little did they know that the Chinese had already arrived here hundreds of years ago and left behind detailed written materials, especially the Qing government had very detailed place name records in the early 18th century. Przewalski seemed not satisfied with the "priority discovery right", and with the arrogance and arrogance of a colonialist, he named the Zhaling Lake and Eling Lake in the source area of the river as "Expedition Lake" and "Russian Lake" respectively.

In 1886, Przevalsky was promoted to major general for his five expeditions to China over 20 years, which helped Russia "expand its territory" and obtain scientific data. He was also the only military explorer of the same period who was promoted to general for his expeditions in China. He was employed by scientific institutions in 44 countries and won medals and honorary titles in many countries. He is already a member of the world’s geographical exploration hall of fame.

In 1888, Przevalsky, who had already achieved success, submitted a Central Asian expedition plan for the fifth time, with only one destination - the only regret in decades of exploration, entering Lhasa, Tibet. It seemed that he was destined to have no chance to go to Lhasa. Not long after the expedition team set out, Przevalsky died of typhoid fever. On his deathbed, he left a will: he must be buried on the shore of Lake Issyk-Kul, and he must wear the expedition uniform when buried. The inscription on the tombstone is "Traveler Przevalsky". Nearly half of his 49 years of life was devoted to exploration, and he was eventually buried in the place named after him, Przhevalsk, and in this way remained in Central Asia forever.