In terms of willingness and strength of naval investment, Italy and Germany are in sharp contrast. Its naval assets are in no way inferior to those of the British and French navies in some aspects. However, with the high cost of naval combat systems today, Italy has also felt that the "single-handed" development is no longer enough. After reviewing the recent development of the Italian naval combat system, this article gives four suggestions. The first is to maintain the foundation. The basic design of the ship should be able to meet its main tasks. The modular and multi-purpose "big cake" should not be eaten too much; the second is to focus on the key technologies and concentrate the limited budget on key technologies; the third is to establish standards and achieve interoperability and open architecture based on this; and finally, to promote cooperation and use the EU and NATO framework to integrate the supply chain, share costs, promote innovation, and achieve cost reduction and efficiency improvement.

Focus on the Greater Mediterranean and Combat Capabilities

The Italian economy is highly dependent on imports and exports, and most of these imports and exports are completed by sea. Located in the center of the Mediterranean, the country is itself an important hub for maritime trade and the blue economy. Therefore, Italy is very interested in the safe transportation of goods through the global public domain. Italy draws most of its energy supply from the Mediterranean, a region rife with instability, illicit trade, tensions and conflicts.

In this context, the Italian Navy is an important tool for Italy to safeguard and promote its interests. Geographically, the main operational focus of the Italian Armed Forces is concentrated around the “Greater Mediterranean”, a geo-economic macro-region of primary strategic importance to Italy’s national interests. This region stretches from the Gulf of Guinea through the Mediterranean to the Red Sea, the Persian Gulf and the Gulf of Aden, and includes not only the Mediterranean littoral area, but also the entire Middle East and North Africa (MENA), the Sahel region and the “Horn of Africa”. According to the strategic guidelines of the Italian Navy, combined with Italy’s geographical location, its manufacturing sector and the heavy reliance of its economy on maritime imports and exports, Italy must declare and defend its interests throughout the oceans and on the world’s main sea lanes of communication. The Arctic region has also begun to attract Italian attention, given the impact of climate change on sea lanes of communication.

The Mediterranean is now under the influence of multiple destabilizing factors, including international maritime disputes and the unresolved crisis and economic stagnation in the Middle East and North Africa. As the U.S. Navy strengthens its presence in the Pacific, Italy will not only play a more prominent role in ensuring security and stability in the volatile Greater Mediterranean, but also has a significant responsibility as a member of NATO and the European Union. In this context, recognizing that the country’s interests are global, the Italian Navy is committed to maintaining a balanced and flexible trench force that can be effective in brown, green and blue water environments.

Since the end of the Cold War, the Italian Navy has increasingly focused on an expeditionary fleet as a means of projecting power in the Greater Mediterranean and protecting sea lines of communication. This is also a particularly useful capability for a country that makes important contributions to global crisis management, counter-terrorism and stability operations. The ongoing maritime security and police operations against non-state actors, such as pirates in the Gulf of Aden and smugglers in the Mediterranean, are prominent examples of this.

Strategic Guidelines (right)

The Russian-Ukrainian conflict and the broader geopolitical confrontation behind it, coupled with the increased threat level in the Mediterranean, have prompted the Italian Navy and the Ministry of Defense to focus more on naval combat capabilities suitable for the common defense of the Euro-Atlantic region and for keeping global sea lanes open and secure in times of tension with peer adversaries. In fact, the Italian Ministry of Defense’s latest 2023-2025 Multi-Year Planning Document (DPP) commits to providing significant funding for the replenishment of its navy’s ammunition (including missiles, torpedoes and naval gun shells) to bring the inventory to a level sufficient to respond to armed conflicts.

Despite the dramatic changes in the global situation in recent years, maritime security operations are likely to continue and will require cost-effective and appropriate capabilities. Therefore, in order to maintain a balanced and evolving fleet, the Italian Navy is likely to achieve a certain degree of diversification and specialization within the fleet. The return to a solid defense and deterrence posture requires comprehensive combat capabilities, coupled with the continuous need to provide maritime security, driving the Italian Navy’s capability development to consider the full spectrum of high and low ends.

Planned Fleet Development

The Italian Navy’s Strategic Guidelines for 2019-2034, drawn up before the 2022 Russian-Ukrainian conflict, proposed the minimum level of assets required to perform the Navy’s mission at that time, envisioning an overall balanced structure based on 1 aircraft carrier, 4 amphibious landing/assault ships, 4 destroyers with sea-based ballistic missile defense capabilities, 10 frigates, 8 conventional submarines, 7 medium patrol ships and 8 light patrol ships, 12 new generation minesweepers, 3 logistics supply ships and 3 hydrographic-oceanographic survey vessels. At that time, the Navy’s Strategic Guidelines also took into account the potential growth of the Navy’s capabilities, as it clearly stated that the envisaged force structure was not the Navy’s optimal outcome, but the minimum solution proposed for the tasks to be performed by the fleet within the scope of existing resources. This potential growth should be raised in the iterative gap analysis, demand definition, and subsequent strategic force planning process. Currently, the Italian Navy is reconsidering an updated capability development structure to incorporate the Russian-Ukrainian conflict and related changes in the international security environment. Such a structure may prioritize the development of the high-end capabilities mentioned above, including cutting-edge technology and a larger inventory of ammunition that determines the outcome of battles, in order to build a navy with greater lethality and effectiveness.

The latest official Italian Navy documents continue to establish as a minimum requirement the capability of a maritime task force at the level of the Navy Component Command (2 stars), which will include 1 aircraft carrier strike group and 1 amphibious task group (ATG), which can project power to and from the sea. In fact, Italy is currently one of the two Mediterranean countries with aircraft carriers (the other is France). The Cavour makes Italy the navy with a fifth-generation multi-purpose short take-off and vertical landing (STOVL) fighter, which is unique on the European continent and only three in the world, the other two being the British Navy, the US Navy and the Marine Corps.

Over the next 10 years, the Italian Navy will continue to replace old ships with new ships with larger displacement and stronger combat capabilities, especially (but not limited to) destroyers, frigates, corvettes, logistics support ships (LSS) offshore patrol ships and amphibious ships. For example, the Bergamini-class European multi-purpose frigate has a full load displacement of 6,700 tons and carries more weapons than the previous generation Mistral-class (full load displacement of 3,040 tons) and Wolf-class (full load displacement of 2,500 tons). Italian destroyers seem to be following the same path. The next generation of destroyers may have a full load displacement of 10,000 tons, while the current Horizon-class destroyers are 7,050 tons.

As tensions escalate, the Italian Navy has observed that the Russian Navy has strengthened its presence in the Mediterranean, and the underwater threat is imminent. Therefore, after the outbreak of the Russian-Ukrainian conflict, strengthening capabilities and lethality has become more urgent for the Italian Navy. Italian Chief of Defense Staff Admiral Cavo Dragone reminded people that they must pay attention to the underwater threat posed by the Russian Navy in the Mediterranean and strengthen the navy’s capabilities accordingly. At present, except for the P-72A anti-submarine patrol aircraft, the Italian Navy lacks fixed-wing anti-submarine patrol capabilities-a capability that is considered necessary. Procurement The former is a transitional solution to maintain maritime surveillance capabilities after the retirement of the Breguet P-1150 patrol aircraft, which was specially built for anti-submarine warfare. Moreover, Enrico Credendino, Chief of the Navy Staff, proposed at the Joint Defense Committee of the Italian Parliament that the naval fleet also needs more ships dedicated to air defense and anti-submarine warfare in order to maintain appropriate force rotations.

The amphibious capabilities of the Italian Navy, which for many years have been based on three old "San Giorgio" class dock landing ships, are now undergoing a major renewal process that will significantly enhance Italy’s two-armed combat potential. The process begins with the first new generation helicopter dock landing ship "Trieste", which will be delivered to the Italian Navy in 2024 and become the largest warship built in Italy since World War II. "Trieste" will not only serve as a helicopter platform, but will also carry F-35B fighters when necessary: making it the most versatile helicopter dock landing ship in the world.

According to reports in May 2023, the Italian Navy is still planning to purchase three amphibious dock transport ships (LxD. "x" stands for multi-purpose), whose characteristics confirm the trend described above - the size of a single ship is increased, with a displacement of 16,500 tons and a length of 165 meters, while the two data of the "San Giorgio" class are 7,700 tons and 133 meters respectively. However, the new amphibious ship no longer uses a full-length deck, and its rear flight deck can only accommodate two helicopters.

The Italian Navy is also looking to update its minesweeping fleet. Future ships are also larger than previous models and are expected to be equipped with a variety of unmanned systems.

In terms of fleet modernization, Italy is the coordinator of the European Patrol Ship Long-term Structured Cooperation Program, which is currently in the development stage thanks to the financial support provided by the European Defense Fund through the "Modular Multipurpose Patrol Ship" twin project. Under the coordination of Naviris, a joint venture between Fincantieri of Italy and Naval Group of France, the modular multipurpose patrol ship is implemented by a multinational industrial consortium, and it is very likely to involve naval combat systems from suppliers such as Lepinado. The "Multi-Year Planning Document" predicts that eight such warships will be purchased to replace old offshore patrol ships. Similarly, the displacement of the European patrol ship is also larger than that of the previous generation.

Broadly speaking, the trend towards increasing displacement of multi-class ships means being able to meet the following needs: equipping more and more advanced combat systems while leaving space for upgrades and possible accessories; and leaving green water to perform missions in the Greater Mediterranean. As mentioned above, in the context of changes in the international security environment, the Italian Navy will pay more attention to high-end naval combat capabilities (which has been confirmed by its investment in modern fleet combat systems) while maintaining the ability to perform low-end activities such as maritime security operations.

Overview of Naval Combat Systems

The Italian Navy plans to purchase new combat systems that can substantially change its naval combat and force projection potential, starting with long-range strike capabilities - cruise missiles equipped with frigates, destroyers and submarines. The "Teseo" MK2/E missile manufactured by the European Missile Group is developed from the "Otomart" anti-ship missile and will be equipped on the next generation of destroyers and multi-purpose offshore patrol ships (PPA), and will replace the existing "Otomart" missiles on European multi-purpose frigates and "Horizon" class destroyers. The system is significantly improved over its predecessor and can strike ships and land targets from more than 350 kilometers away, greatly enhancing the Italian Navy’s ability to strike deep into enemy territory. Interestingly, the multi-purpose offshore patrol ships are designed using a modular approach, but the Italian Navy’s current goal is to equip all multi-purpose offshore patrol ships with a full set of naval combat systems. In addition, the Italian Navy aims to equip fixed-wing aircraft with powerful standoff weapons, replacing the helicopter-launched "Marte" MK/2S air-to-surface missile with an extended-range version (up to 100 kilometers) capable of striking ships and shore targets. This development is clearly due to changes in the threat level and the necessary missions of the military.

In recent years, the Italian Ministry of Defense has planned to equip four next-generation destroyers and U212NFS submarines (the first to be delivered in 2027) with long-range deep strike cruise missiles - but it is not clear whether the Italian Navy will purchase the European Missile Group’s "Storm Shadow" or Raytheon’s "Tomahawk". The Russian-Ukrainian conflict highlights the importance and urgency of this capability. The U212NFS submarine will also be equipped with Leonardo’s "Advanced Black Shark" (BSA) heavy torpedo, which is a development of the "Black Shark" torpedo, with the goal of gradually replacing the Cold War-era A184 torpedo. Italian naval ships and aircraft are also currently equipped with or gradually introducing the European Torpedo Company (Eurotorp) MU90 light anti-submarine torpedo.

At the end of 2022, the total number of fixed-wing and rotary-wing aircraft in service in the Italian Navy reached 100, most of which are modernized (or undergoing modernization) high-performance models. This capability will soon be strengthened by the purchase of ship-borne fixed-wing and rotary-wing drones dedicated to intelligence, surveillance and reconnaissance operations. As Leonardo has become a joint venture partner of NATO Helicopter Industry (NH Industries) together with Airbus Helicopters and Fokker, the Italian defense industrial base has also participated in the NH90 project. The Italian Navy will purchase 46 SH-90 helicopters suitable for naval and anti-submarine warfare. As part of the Italian Navy’s modernization process, the SH-90 will gradually replace the old Augusta AB-212 fleet and form the Navy’s helicopter anti-ship and anti-submarine warfare capabilities together with Leonardo’s AWW101. The Navy’s EH101 (which entered service in 2001) will soon undergo a mid-term update, followed by a software and capability upgrade of the NH-90 fleet, which will modernize the Navy’s rotorcraft capabilities and bring the onboard systems of these helicopters to modern standards. The Navy has also purchased 10 MH-90 helicopters (a tactical transport variant of the NH-90) for tactical transport in amphibious operations and special forces operations. The purchase of the AW "Hero" rotary-wing drone is under discussion.

As mentioned earlier, Italy is one of only three countries in the world that operates F-35B fighters on aircraft carriers, a capability that gives the country’s navy a high degree of interoperability with NATO allies in aircraft carrier operations. As of June 2024, the Italian Ministry of Defense has approved the purchase of a total of 30 F-35B fighters, evenly divided between the Navy and the Air Force. Italian Chief of Defense Staff Admiral Cavo Dragone said that although this number is not enough to complete the tasks assigned to the army, the F-35Bs of the Navy and the Air Force may operate jointly when necessary. In fact, the two services have begun joint exercises and simulations involving new multi-mission aircraft, including from the "Giant Cavour". The F-35Bs of the Italian Navy and Air Force have also landed on the British Navy’s "Queen Elizabeth" aircraft carrier, and two US Marine Corps F-35Bs took off from the British aircraft carrier and landed on the "Giant Cavour".

The air defense capabilities on Italian naval ships are entrusted to a combination of various surface-to-air missiles - mainly "Aster 15" (short-range) and "Aster 30" (medium-range) - and naval guns (such as Oto-Melara 76/62 and 127/64 light naval guns). The Italian Navy recently procured the first batch of DART guided artillery shells for the Oto-Mellara 76/62 guns, which it considers a more effective means of engaging maneuvering missiles with the 76mm naval guns.

The planned procurement of the Volcano 127mm unguided extended range (BER) and guided long range (GLR) ammunition will bring a leap forward in the Italian Navy’s precision artillery strikes. The guided long range ammunition, in particular, will bring unprecedented range and accuracy to the Italian Navy’s fire support missions against ships or coastal targets.

Navy’s vision of system integration in naval warfare

The "Ministry of Defense’s Multi-Domain Operations Approach" published by the Italian Defense Staff in 2022 outlines the Italian military’s approach to aligning with NATO’s operational doctrine in this regard. The document describes the various operational domains as "interrelated single environments" in which the careful coordination and alignment of efforts can help achieve greater results than a single domain approach. To some extent, multi-domain warfare is not a new concept for the Italian Navy. Relying on space-based and cyber effectors, the army has the ability to fight on the surface, in the air, underwater and even under the sea.

From the perspective of the Navy, the boundaries of various domains are constantly blurring, requiring new concepts of naval warfare, which are explained in great detail in the concept of "Future Naval Combat System for Multi-Domain Operations 2035" (FCNS 2035).

"Future Naval Combat System for Multi-Domain Operations 2035" integrates the Italian Navy’s vision for the future, with a special focus on the development and application of new technologies in naval warfare. In order to respond to threats and the development of disruptive technologies, the "Future Naval Combat System for Multi-Domain Operations 2035" lists the integrated air and missile defense (IAMD) surveillance capabilities from sea level to 100 kilometers, as well as directed energy weapons.

In addition, in the area of underwater warfare, the Navy must be able to conduct continuous operations without depth restrictions (also in the protection of critical infrastructure) and deploy a fleet of autonomous vehicles. The damage to the Nord Stream pipeline in 2022 highlighted the need to protect seabed pipelines and cables, especially (but not only) in the Mediterranean basin. To this end, surface ships, submarines and aircraft must develop into "strategic hubs" capable of generating clustering and significant effects wherever needed, including launching and recovering unmanned systems with various payloads. Since the average depth of the Mediterranean Sea (1,450 meters) is much greater than that of the Baltic Sea, the development of appropriate underwater capabilities is very challenging. This vision of future capabilities foresees that manned and unmanned assets must be highly integrated, especially since the "Future Naval Combat System for Multi-Domain Operations in 2035" requires each platform to act as a "theater" combat command and decision-making center, thanks to data fusion capabilities, artificial intelligence and the ability to manage data at the edge of the battle.

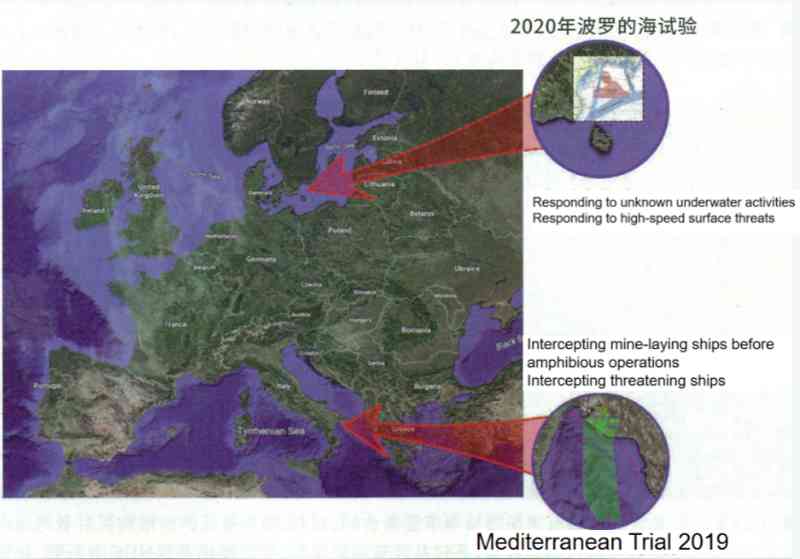

In this context, Italy has led a coordinated effort involving the Navy and industry to achieve a higher level of unmanned system integration in a multinational operational environment, as demonstrated by the successful OCEAN 2020 project led by Italy with funding from the European Union’s Action for the Preparation of Defense Research (PADR). OCEAN 2020 is the largest PADR project coordinated by Leonardo, which leads a consortium of more than 40 European partners from 15 EU countries, including industrial companies, navies and research centers. The main goal of the project is to demonstrate, through two maritime demonstrations in the Baltic Sea and the Mediterranean Sea, that situational awareness in the maritime environment can be enhanced through the operation and integration of multiple unmanned systems.

Meanwhile, the Italian Navy will continue to procure the next generation of unmanned systems. In fact, FCNS 2035 identifies unmanned systems as a priority for the Navy. The Italian Navy already operates the HUGIN 1000/HUGIN3000 and REMUS 100/REMUS 300 main unmanned underwater vehicles equipped with the latest sensors. In terms of future capabilities, given the results of the OCEAN 2020 maritime demonstration, the Italian Navy is currently considering multiple options, such as Leonardo’s AW "Hero" multi-purpose rotary-wing drone, which participated in the OCEAN 2020 maritime demonstration and has a wide range of missions, including reconnaissance, surveillance, target acquisition and reconnaissance (ISTAR).

Generally speaking, the Italian Navy has shown a clear interest in the development and use of more complex unmanned platforms in the maritime domain. In fact, the Italian Navy regards unmanned systems as assets that can be used for specific missions (such as ISTAR, anti-submarine warfare, seabed warfare, mine warfare and logistics), and through a manned-unmanned combination approach, it will also improve and broaden the fleet’s combat capabilities in naval warfare. At the same time, the Italian Navy continues to invest in the automation of multiple systems to improve naval combat capabilities and reduce the workload of operators and the number of people required on board, thereby reducing the space and services required for personnel on existing and future ships. The achievements in this regard are encouraging: the Ardito class destroyers displace 5,000 tons and have a crew of 400, while their successor, the Doria class, displace 7,000 tons and have a crew of 200. However, human resource challenges remain, as the operational tempo continues to increase and Italian ships are increasingly deployed for long periods of time.

Italian Navy and Defense Industry

Traditionally, the Italian defense industrial base has been able to meet the needs of the Navy due to the presence of larger defense industry players - Leonardo and Fincantieri - as well as companies specializing in electronic warfare, space and missiles, plus innovative small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs).

Leonardo is a leading industrial company in the global defense sector, with total revenues of €14.1 billion, 83% of which comes from the defense sector. In terms of naval combat systems, the company produces a wide range of products, which in fact covers almost the entire field, which is also characteristic of Italian companies. In particular, Leonardo’s Electronics Division focuses on advanced sensors (including radars such as Cronos, optical sensors and underwater sensors), advanced communications equipment, naval gun systems, guided and unguided munitions, missile systems, torpedoes and combat management systems. Its products include shipborne artillery (such as the 76/62 super rapid-fire gun, which is the most widely used model of its kind, with customers including navies of more than 60 countries).

Leonardo has invested in the development of a separate "Integrated Workstation for Ships" (PICN). The result of this move is the SADOC MK.4., which is now equipped on the first batch of multi-purpose offshore patrol vessels (PPA) of the "Tavon di Revel" class in service with the Italian Navy. The acquisition of a stake in Hensoldt will strengthen Leonardo’s capabilities in defense electronics. In terms of helicopters dedicated to maritime operations, the company is also a market leader with the AW 101 and NH 90FH mentioned above. As for the Italian Navy’s fixed-wing assets, the company participates as a second-tier partner in the US-led F-35B joint production venture, managing the Cameri General Assembly and Checkout (EACO) facility, which assembles the F-35 fighter jets used by the Italian army.

Fincantieri Maritime Group is one of the world’s largest shipbuilding groups. With the Fincantieri Marinette shipyard, its warship-related shipbuilding business has also expanded to the United States. In 2021, the group’s revenue in the defense field reached 1.42 billion euros. Fincantieri builds almost all ships of the Italian Navy, ranging from large surface combat ships to submarines, minesweepers and offshore patrol ships. It is an important player in the field of European naval defense, also thanks to cooperative projects such as U212, "Horizon" European multi-purpose frigates and European patrol ships. Through its US subsidiary, Fincantieri has obtained the US Navy’s future missile frigate "Constellation" class project-a total of 20 ships may be built. In addition, Seastema, a subsidiary of Fincantieri Group, is also involved in the construction of new frigates for the South Korean Navy and the design of a new aircraft carrier.

Many of the Italian Navy’s capabilities in the fields of electronic warfare and electronic support measures were developed by Elettronica, some of which are compatible with naval combat applications or developed specifically for the latter. These capabilities include the SEAL naval countermeasures system family designed for multiple classes of ships. In addition, the NETTUNO-4100 electronic countermeasures system is designed to counter incoming missiles and long-range target indication radar systems. Other systems developed by Elettronica include the Loki early warning and command system, which is also used in the naval field, and the ALR-733 airborne electronic support system family developed for maritime patrols. Space is an important enabler of naval operations in terms of maritime imagery, communications and ISR, and here Thales Alenia Space, Telespazio and Avio cover both upstream and downstream and the entire space value chain. One project with a particular connection to the maritime sector is the Mediterranean Basin Observation Small Satellite Constellation (COSMO-SkyMed), an Italian dual-use radar imaging satellite constellation.

Finally, MBDA is a leading European missile system designer and manufacturer, including the Telesio MK2/E, Malte MK/2S/ER and the Aster 15/30 missiles.

Among the SMEs, GEM Electronics is an Italian company specializing in small 3D radars for navigation and maritime/coastal surveillance, as well as electro-optical sensors and inertial systems.

Balanced Navy vs. High-End Capabilities

In terms of the navy, Italy plays a central role in collective deterrence and defense of NATO’s southern flank and contributes to the Alliance’s continental theater threat posture from the Baltic to the Black Sea. This situation, especially the actions of Russian ships and submarines in the Mediterranean, coupled with the adventurous attitude of the Russian leadership, requires the Italian Navy to have sufficient naval combat capabilities to respond. These capabilities include ISR, Mine Countermeasures, Anti-Submarine Warfare, Air and Missile Defense, as well as deep strike and amphibious capabilities. This also means reinvesting in special technologies and specialties such as sonar, underwater surveillance and defense, which have lagged behind other technologies in the past decades.

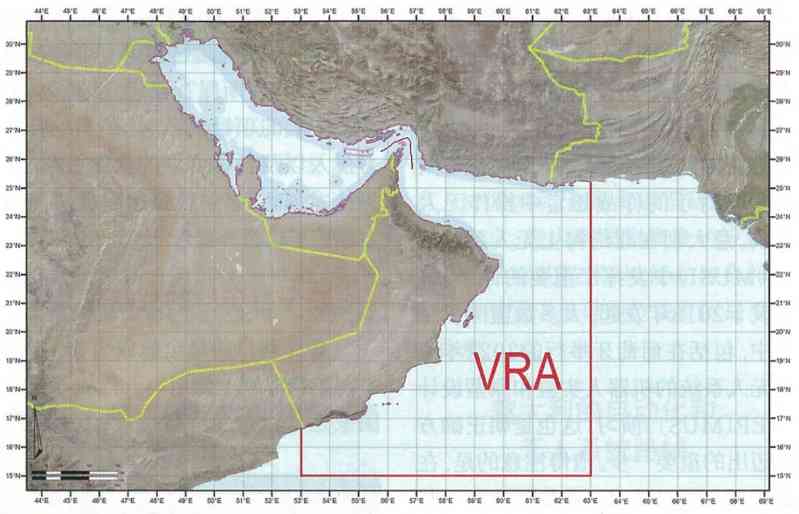

Meanwhile, Italy’s interest in the Greater Mediterranean goes far beyond deterrence and defence. Securing sea lines of communication and maritime energy supplies, combating illicit traffic, developing partner nation capabilities and conducting naval diplomacy all require a range of appropriate maritime security operational capabilities. These operations will most likely continue from the Gulf of Guinea to the Persian Gulf, in accordance with national, regional or European plans (such as the Coordinated Maritime Presence, CMP). At the same time, the strengthening of NATO’s deterrence and defence posture will put Italy at the forefront of the Alliance’s naval southern flank, face to face with the Russian naval fleet. This is more important than ever as several other countries are also strengthening their naval posture in the Greater Mediterranean.

Thus, having spent the last 30 years focusing a large number of Italy’s naval assets on police operations, the Italian Navy (like the other services) must now focus its capability development on the higher end of the operational spectrum, also through the acquisition of additional naval combat systems and/or the upgrading of existing ones. The Italian Ministry of Defence has traditionally respected the objectives of the NATO defence planning process in terms of naval combat systems, and the Cavour Carrier Strike Group and the Amphibious Group reflect the Italian Navy’s commitment to modern operations. It is worth noting that Italy is evaluating the latter operational options to establish a new littoral expeditionary cluster. However, the Italian Navy still needs to make the transition to high-end capabilities and is making this transition, which must be carried out in a balanced and sustainable naval posture that also reflects the various missions performed by the service.

Therefore, the Italian Navy should invest resources to equip combat ships and naval aviation units with complete combat capabilities, including missiles, torpedoes, ammunition (preferably guided munitions) and ensure that the weapons inventory is sufficient to sustain long-term high-intensity combat operations - judging by the Russian-Ukrainian conflict, this is no longer just a theoretical possibility.

This transition to a parity scenario should also be sustainable in terms of human resources. High-end capabilities are more complex, expensive, and more technologically intensive, and they also require more investment in the recruitment, education, training, and career of professional military personnel to maintain a skilled and motivated military community. The number of personnel should also be sufficient to support the demanding combat tempo requirements and ensure a continuous presence in green water or even sea water, as the Italian Navy should be better prepared for long-term and sustained operations.

Skepticism about Multi-Domain Operations

The concept of Multi-Domain Operations has received widespread attention in Western defense policy circles in recent years. It has become a key concept at the NATO level and is likely to influence the European Union as well. Like other innovative concepts originating from the United States, Multi-Domain Operations is deeply rooted in the unique reality of the United States. Individual European countries must consider their ambitions, theaters, force structures, military doctrines, legacy assets, and a series of long-standing practices when determining various combat operations, capability development, and defense industrial policies. They are not on the same level as the United States.

It is clear that the current five combat domains are becoming increasingly interconnected, and these links are increasingly relying on space and cyber technologies (including those for command, control, and communications). In addition, the naval domain has further diversified to cover the seabed, underwater, surface, air, and littoral environments. Aircraft carrier strike groups embody the combination of air power and sea power, while amphibious assault groups form an inherent bridge between the sea, air, and land domains. In and around naval ships, a number of disparate systems must work together. Therefore, the Italian Navy has actually developed an integrated complex systems thinking. All these elements together contribute to the Navy’s multi-domain operations approach.

The Italian Army has already started a long process towards joint multi-service operations in terms of theory, organization and practice. In recent years, Italy has significantly strengthened its Supreme Joint Operations Command (COVI) based on domestically produced technology, and has included all service commands (the Army, Navy, Air Force, and the existing special forces, space and cyber operations joint command) under its jurisdiction. The Italian Army has also developed the concept of "supported-supporting", that is, a clear chain of command can be established between the service leading the joint operation and other services providing support according to their functions. However, in order to fully implement the planned integrated combat model (modello operativointegrato), while maintaining the command capabilities of senior generals such as the Commander-in-Chief of the Italian Navy Fleet (CINCNAV), much work is needed.

In this context, the multi-domain concept should further stimulate Italy to pragmatically strengthen the jointness between the various services, especially to develop and implement the necessary arrangements to make joint operations more effective and avoid unnecessary complications.

In this environment, digitalization and connectivity should be promoted in an efficient, secure and resilient manner when it comes to data flows and management, artificial intelligence, quantum computing and technological sovereignty of military digital infrastructure.

Balance between fleet numbers and systems

Looking forward to the next decade, it may be difficult to draw any overall conclusions from the trends in the number of naval fleets around the world, as each navy is part of a wider defense institution and reflects the unique realities of each country. However, a closer look at the navies of the United States, the United Kingdom, France and Germany shows that most of them are increasing their lethality and integrating a more dispersed fleet supported by a large number of unmanned systems, especially the United States Navy.

In this context, Italy has a strong position in the navy The ambitions in this area should be matched by adequate resources to ensure the effective execution of the short- and medium-term missions entrusted to its Navy. Given the current international security environment, the Italian Ministry of Defense is continuously reflecting on the types and numbers of ships needed, which runs through the current gap analysis, requirements definition and subsequent strategic force planning process. Obviously, in order to ensure a continuous and effective presence in the Greater Mediterranean area, while supporting NATO’s deterrence and defense missions, the Italian Navy needs more capabilities, both ships and combat systems.

Because of the aforementioned shift to high-end combat assumptions and the increasing importance of naval combat systems, the number of ships Any increase in fleet size should be accompanied by appropriate investments in these systems and ammunition inventories (and spares), which are necessary to ensure the effectiveness, lethality and survivability of ships in high-intensity naval warfare scenarios. In this context, priority should be given to strengthening anti-submarine, anti-mine, missile defense and deep strike capabilities.

Evaluations of fleet numbers and system balance should also consider the effectiveness of older legacy platforms using the latest components and technologies (especially naval combat systems). At the same time, innovations in maintenance methods should help shorten the time of maintenance, repair, overhaul and upgrade (MROU) activities and improve the combat readiness and effectiveness of assets.

Modularity should be approached with great care

Modularity is important for the Italian Navy, but it should be pursued in a pragmatic way. In fact, unless a ship is truly fully modular from the outset, and the modules used do exist and are ready for installation, it may take two years in the shipyard to replace a certain naval combat system. In other words, modularity can only work when there is pre-designed space on the ship to quickly install modules that do not change the most important mission assigned to the ship (i.e. special forces or medical modules). Therefore, each ship should be designed to successfully perform its primary mission and perform secondary missions in a satisfactory manner, ensuring a certain versatility. For example, an excellent high-speed minesweeper can serve as a good patrol ship in brown and green water areas with free (or semi-free) passage. In this way, the entire fleet can perform a designated series of missions while ensuring high performance. From this point of view, future ships should include all the envisioned combat capabilities from the outset but also have the ability to install new weapons at any time - such as directed energy weapons - without having to rebuild the entire ship.

A new approach to naval combat systems

The importance, performance, complexity, procurement and operating costs of the Italian Navy’s combat systems are set to rise steadily in the near future, as the pace of technological innovation accelerates. To meet the challenges of this reality and to exploit the associated opportunities, a new approach is needed in the formulation of capability development, procurement and innovation policies.

Firstly, the design of future new generation ships should pay more attention to the available free space on board, energy sources other than propulsion, storage and refrigeration capacity, electromagnetic compatibility, protection against nuclear, biological, chemical and radiological threats, and more broadly the various features required to accommodate more advanced, complex and very different naval combat systems, including unmanned systems. Larger hulls will greatly help in this regard, as well as in terms of the ship’s self-defense capabilities, resilience and navigation capabilities in blue water.

Secondly, while some of these systems must be distributed throughout the fleet, other capabilities (such as anti-submarine warfare and missile defense) require, to a certain extent, specialized ships, in line with the fundamentals of naval warfare.

Third, from the perspective of ships and naval combat systems, the Italian Navy’s technological innovation and procurement methods should make the renewal and upgrading of the entire ship life cycle more effective, rapid, frequent and convenient, beyond the current mid-term upgrade method.

Fourth, navigation and naval combat systems should be designed according to a common set of standards as much as possible to facilitate smooth and seamless integration into larger integrated complex systems, even those provided by different companies. Interoperability and open architecture of systems are key elements in this regard. Here, NATO can play an important role through standardization, and Italy should continue to be forward-looking within the framework of the alliance.

The European patrol ship and DDX projects are an important testing ground for the application of the naval combat system renewal method, and will also require the Italian Navy and industry to work closely together from the early stages of the project in order to wisely control its development phase. This approach should also avoid the joint procurement of the European patrol ship, which ultimately results in too many and too different modifications, which will undermine the economies of scale, innovation and effectiveness of the project.

A smart process of technological innovation

As technological innovation accelerates, and some disruptive technologies are developed in the civilian market, the challenge facing European armies (including the Italian one) is how to deal with a process that is not entirely driven by them. Moreover, hull-related technologies are generally evolving incrementally, while the pace of innovation in naval combat systems is accelerating, and disruptive technologies such as hypersonic weapons, artificial intelligence and autonomous vehicles will profoundly affect future naval warfare. Finally, the cost of electronic equipment, sensors, combat management and weapon systems will continue to grow compared to hulls, propulsion units, etc.

To meet these challenges in the naval field, Italy must fully and continuously invest in key technologies for naval warfare in order to develop, test and improve important components of current and next-generation ships. Innovation regarding certain technological components must be systematically supported, and the risk of failure must be accepted in order to lay the foundation for the subsequent procurement of appropriate capabilities - given that some key disruptive technologies are only developed in the military field. Therefore, the entire Italian Ministry of Defense (especially the National Equipment Directorate) should undergo a major conceptual, legal and organizational transformation to embark on a smart path of technological innovation.

Useful lessons can be learned from the Italian aerospace sector. For example, the technology used in the sixth-generation fighter will be invested and developed during the procurement of the fifth-generation fighter in order to prepare various components and pave the way for the generational leap. Obviously, the future naval combat system is more complex than the future air force combat system. The most important thing is to have a series of coordinated naval plans to deal with different technologies and systems as a catalyst and incubator for technological innovation related to the Italian Navy. Some mature technologies should be used in existing ships within the scope of upgradeability, or quoted on the European patrol ships and DDX being purchased. A systematic cross-fertilization between the military and civilian sectors should be achieved, while ensuring that all technological components of the Ministry of Defense’s capabilities are built according to safety-based design principles.

Such a smart process of technological innovation, and indeed the entire Italian Army, would greatly benefit from a re-formulated National Military Research Program (PNRM), which significantly increases the budget and focuses it on limited priorities. The PNRM should also be better aligned with the European Defense Fund to achieve synergies and help the Italian Ministry of Defense and defense industry focus on priority areas involving European cooperation and competition, especially facing the most demanding challenges that cannot be mastered by a single country. Therefore, only by deciding how to address each technological field at a strategic level can national, international and EU R&D projects be fundamentally coordinated. By extension, Italian national funds should also be used to develop qualified technologies in order to take the lead or play the most important role in cooperation with partners.

Italy’s path to automation and unmanned systems

The Italian Navy sees automation as an important opportunity to reduce the workload of the crew and the number of sailors and officers needed to operate the ships, and to increase the effectiveness and efficiency of the Navy’s operations. This, in turn, can save valuable space on board and, in some cases, address the long-term recruitment challenges caused by slowing and aging populations – but the number of crew members cannot be reduced below a certain threshold, otherwise the ships cannot be guaranteed to be efficient, safe and flexible. Italy should continue along this path, taking advantage of the opportunities provided by big data and artificial intelligence, and aiming for the next leap in automation by investing in projects at national, international and EU levels. At the same time, the Italian and NATO armed forces should work to clarify the boundaries of artificial intelligence and automation at the operational level.

Unmanned vehicles also present important opportunities in the context and constraints of a European middle power such as Italy. In this regard, the approach outlined by FCNS 2035, which considers unmanned systems as valuable assets and ships of different classes as their management centers, appears to be a pragmatic approach to the effective application of manned-unmanned teaming (including multi-unmanned teaming). Small unmanned systems will be increasingly used for ISR, special forces frogman operations, (in some cases) minesweeping, transport and logistics, and maritime security operations in a broad sense of permissive or semi-permissive environments. Most importantly, unmanned systems are key to ensuring the Italian Navy’s presence (mainly including but not limited to ISR) in vast areas of operation that cannot be covered by manned assets.

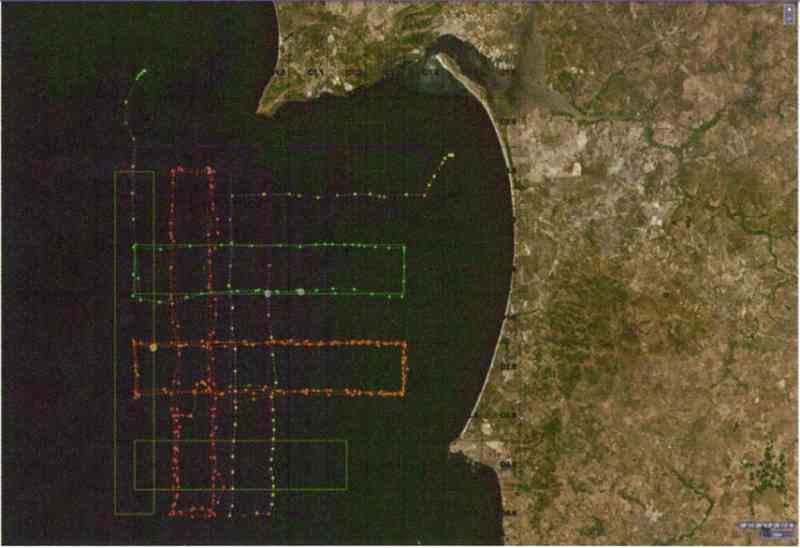

Also on the basis of the results of OCEAN 2020, the integration of unmanned systems and rotary-wing drones should not only be advanced as quickly as possible in terms of technology, but also in terms of doctrine, procedures and organization, while investing in the necessary cyber defense capabilities to operate unmanned vehicles in combat scenarios with peer competitors. Italy has played an important role in the NATO Maritime Unmanned Systems Initiative (MUSI), which was launched in 2018 and in which most allies participated, including the 2022 Robotic Experimentation and Prototyping of Maritime Unmanned Systems (REP[MUS]) exercise held in Portugal, which is also an important step in the right direction. It is worth noting that in some areas, such as rotary-wing drones and manned-unmanned teaming, Italy can significantly enhance its technical capabilities and play a leading role in Europe and beyond.

Finally, quantum computing could play a disruptive role in the field of unmanned systems, ensuring unprecedented levels of encryption between various manned and unmanned assets, and promising to provide submarines and other ships with far greater autonomy than is currently possible through satellite positioning, navigation and time services.

Focus on the underwater environment

The underwater environment (including the seabed) is the next frontier of naval threats. Indeed, the harsh reality of the damage to the Nord Stream pipeline in 2022 is a reminder of the increasing vulnerability of critical infrastructure such as Internet cables and energy pipelines to new technologies that can be applied in underwater environments. Potential attacks on underwater infrastructure are a real threat to Italy’s national security, as well as the economic interests of the Greater Mediterranean and beyond. Therefore, in 2022, the Italian Navy deployed additional capabilities to protect underwater pipelines that are critical to Italy’s energy security, broadening and strengthening the "Secure the Mediterranean" (Mediterraneo sicuro) operations.

The Italian Navy should design a new approach for this environment, fully integrated into the overall military posture of the Italian Ministry of Defense and focusing on the capabilities required to fully operate underwater and on the Mediterranean seabed. Italy should seek a Advanced underwater situational awareness capabilities. Given the characteristics of this environment, the development of unmanned underwater vehicles, sensors and communications are key elements to ensure a sustained military presence in priority areas. The project to establish the National Underwater Environment Center in Spezia is characterized by full government commitment and public-private partnerships, which create opportunities for technological innovation, concentrated investments and the development of dual-use capabilities.

Members of the Italian Navy attended.

The strategic significance of the carrier strike group

Italy is currently one of only three countries in the world to operate fifth-generation fighters on its aircraft carriers, which is an extremely valuable asset both politically and militarily. Considering the high-intensity scenarios, deterrence and defense mentioned above, this asset will remain valuable even if a few other countries also deploy fifth-generation aircraft on their ships in the future. As more F-35Bs enter service in the Italian Navy, the necessary strategic approach should be developed to employ its carrier strike groups, both in terms of operational plans and in terms of raising political awareness of the impact, benefits and potential of this unique sea-based capability in terms of power projection. As the multinational nature of carrier strike groups deployed by French and British aircraft carriers in recent years has shown, for example, this capability is a valuable tool to increase interoperability when rallying allies under the Italian flag, and also marks a temporary but meaningful presence in the Greater Mediterranean and Indo-Pacific regions. Furthermore, it should be understood that the carrier strike group is one of the key pillars of deterrence and defense capabilities in the naval domain, also in high-intensity conflicts.

The multiplier effect of international cooperation

Italy is fully aware of the importance of international cooperation in the maritime domain, as its Mediterranean Security and Defense Strategy considers action and cooperation as equally important pillars of the Italian strategy. The Italian Navy sees that the activities of multiple state and non-state actors in the Greater Mediterranean, as well as the network of dual-line and regional relations, have made the Mediterranean basin itself a rather crowded environment. The importance of partnership and cooperation is reflected in the "Inter-regional Maritime Power Seminar", a meeting regularly organized by the Italian Navy in Venice, attended by more than 50 navies and 100 international organizations. From the Italian and Italian perspectives, cooperation with allies is essential to make up for the gaps in their respective capabilities, such as the US P-8A maritime patrol aircraft stationed in Sigonella, which strengthens NATO’s fixed-wing anti-submarine warfare capabilities in the Mediterranean. It is particularly worth mentioning that the Italian Navy has been developing strong cooperation with the United States, the United Kingdom and France, maintaining regular contacts with the Mediterranean littoral countries.

The Italian Ministry of Defense should maintain this pragmatic approach, take advantage of the advantages provided by bilateral, regional, EU and NATO frameworks, develop cooperation with partners and allies in maritime security operations, and continue to build capabilities and innovations. In terms of operations, missions such as the European Coordinated Maritime Presence and the European Lake Surveillance Program in the Strait of Hormuz (EMASOH) are good examples that can be replicated in the Mediterranean basin.

As for the formation of capabilities, the European patrol ship is a touchstone for Italy’s leading cooperation with France, Spain and Greece within the framework of the European Union. It is hoped that this will produce an asset that is as standardized as possible (although there will be modifications for each country) and can compete in the global market with the support of an integrated supply chain. As for innovation, in the context of NATO, the Marine Research and Experimentation Center (CMR&E) in Spezia should be an opportunity to build an innovation benchmark in the city, linking the facilities and investments of the Italian Navy, Leonardo, Fincantieri and other naval-related technology companies (including the National Underwater Center mentioned above) and small and medium-sized enterprises.

Broadly speaking, the European Defense Fund, the European Defense Agency Innovation Center, NATO’s Maritime Research and Experimentation Center and the NATO North Atlantic Defense Innovation Accelerator (DIANA) are international channels that Italy is exploring with its partners and allies to achieve the economies of scale and multiplier effects required to produce technological leaps, not only focusing on interoperability, but also on the interchangeability, commonality and integration of naval assets. To achieve this goal, Italy must incorporate clear concepts and sound plans into cooperation, make sufficient investments, and achieve win-win solutions with important partners on an equal basis, coupled with strong public-private partnerships and the commitment of the whole government.