As naval combat systems become increasingly expensive, individual European countries are increasingly unable to cope with them. In recent years, projects led by medium-sized countries and named "Europe" are common, including the "European Multipurpose Frigate" (FREMM), "European Unmanned Aerial Vehicle" (Eurodrone), "European Patrol Ship" (EPC), "European Guard Ship" (EUROGUARD), etc. With the increase of such projects, various cooperation mechanisms at the EU level have also emerged.

The significance of the naval field to the EU

The EU remains the world’s largest exporter and second largest importer, and sea lanes are crucial to its imports and exports. In fact, the vast majority of Europe’s foreign trade goods (90%) are transported by sea. In 2022 alone, 3.48 billion tons of goods were handled in major European ports.

At the same time, the return of great power competition and the confrontation sought by Russia have deeply affected the naval field. As the focus shifts back towards high-intensity, peer competition, the EU can play an important role in encouraging collaboration, including through financial incentives through the EU Defence Initiative, as Member States plan to develop and procure the latest combat systems in the naval domain. The EU sees maritime security as key to its fundamental interests. Indeed, the Strategic Guidance states that the naval domain is a priority area in which its Member States intend to invest, with the aim of developing new and improved capabilities and innovative technologies to address existing deficiencies and reduce dependence on non-EU countries.

The EU is determined to have a complete maritime combat capability, with freedom of manoeuvre, power projection and support stability, while protecting its forces in the maritime domain. To this end, the EU prioritizes interoperability that can ensure superiority at sea and undersea. This is evidenced by the inclusion of the categories of naval mobility and undersea control in the European Defence Agency’s (EDA) Capability Development Priorities (CDP).

Trends in EU maritime domain activities

The EU adopted its first Maritime Security Strategy and its associated Action Plan in 2014. According to this strategy, developments in the field of surveillance and information sharing are very beneficial to improving the EU’s maritime security awareness, and the European Defense Agency’s capability development priorities document describes it as one of the key factors for naval operations and mobility. In March 2023, the EU released a new version of the Maritime Security Strategy, which continued many of the principles in the first version of the strategy, but the difference was that it emphasized strengthening capabilities in several areas, including ensuring the EU’s surface superiority, maritime power projection, ensuring underwater dominance, and air defense.

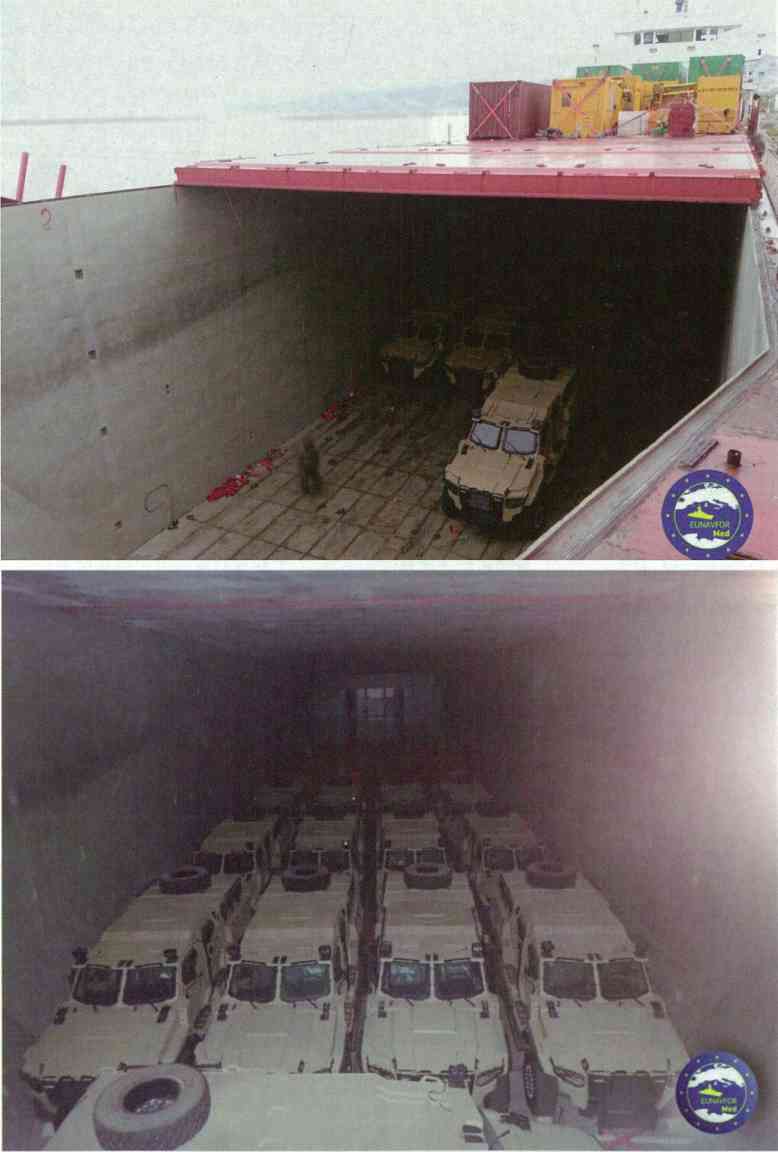

The EU has participated in many naval operations over the years. The EU Somalia Naval Force (Operation Atalanta) is an important example. The goal of this force is to promote peace and stability in Somalia and the Horn of Africa, while strengthening regional security by protecting vulnerable ships in the area of operation. Another related EU maritime operation is the European Mediterranean Naval Force (better known as Operation Sophia), whose goal is to combat human trafficking and smuggling in the Mediterranean. This operation ended in 2020 and was replaced by the European Mediterranean Naval Force (Operation Irini).

In addition to EU missions, the EU Coordinated Maritime Presence (CMP) mechanism is recognized in the Strategic Guidance as a flexible means for willing and capable member states to share maritime perception, analysis and information obtained when deployed in areas of EU interest. Relevant examples include the Gulf of Guinea and the Western Indian Ocean, where the EU Coordinated Maritime Presence mechanism helped provide a bridge between Operation Atalanta and the European Maritime Surveillance Program in the Strait of Hormuz (EMASOH).

EU maritime activities pay great attention to maritime situational awareness. This is also the main goal of OCEAN 2020, an initiative dedicated to integrating unmanned autonomous systems and building a common maritime picture to enhance maritime situational awareness. On the other hand, the EU is less active in naval warfare. To advance capabilities in these areas, the EU is implementing a number of projects within different frameworks, which will be discussed further below.

EU related programs

Permanent Structured Cooperation (PESCO)

The rapid development and endless proliferation of mines pose a potential threat to EU maritime operations. This risk is exacerbated by the use of mines by non-state actors. At the same time, submarine attacks are another growing threat. Maritime Mine Countermeasures (MMCM) and Anti-Submarine Warfare systems have been identified as key to enable EU navies and operations to exercise appropriate underwater control, contributing to their maritime resilience. To this end, the EU is involved in several programs to develop and deliver a range of detection, defense and response systems for use at sea or underwater.

Through the Permanent Structured Cooperation framework, some EU Member States are carrying out activities aimed at countering these (and other types of) threats. First, the Maritime (Semi)Autonomous Mine Countermeasures (MASMCM) project aims to provide Member States with differentiated (semi)autonomous underwater, surface and air mine countermeasures technologies to improve EU maritime security. The Maritime Unmanned Anti-Submarine System (MUSAS) project aims to establish the most modern command, control and communication (C3) service architecture for anti-submarine warfare, allowing EU Member States to counter adversary area denial operations.

The Medium Semi-Autonomous Surface Vessel (M-SASV) project aims to develop a medium-sized surface vessel with multiple mission modules. This semi-autonomous surface vessel will be able to operate unmanned and ensure switching to manual control when necessary.

Italy is currently leading the Port and Maritime Surveillance and Protection (HARMSPRO) project to confirm its prominent position in the Permanent Structured Cooperation Framework, which is committed to new maritime capabilities and enables EU Member States to ensure appropriate surveillance and protection of maritime traffic and facilities through enhanced command and control capabilities. Rome is also involved in the European Escort Essential Elements (4E) project, whose goal is to develop a comprehensive surface warfare system that combines combat systems, communications and information systems, navigation systems, platform management systems and system integration.

Finally, the European Patrol Ship, led by Italy, with the participation of Italy, France, Spain and Greece, is one of the most important Permanent Structured Cooperation projects. Under the framework of the Permanent Structured Cooperation, the participating countries worked together to define the common requirements for this new ship, initially reaching a consensus on two versions: a long-range patrol version for France and Spain, and a shorter-range version more focused on combat missions, favored by Greece and Italy.

European Defense Fund

The EU is also strengthening the joint development of new defense systems and capabilities, including in the maritime field, through calls for projects funded by the European Defense Fund. The fund launched its first call in 2021 and provided funding for 61 winning projects the following year. Of the 924 million euros invested by the European Defense Fund in 2022, 130 million euros are targeted at naval operations and 55 million euros are dedicated to underwater operations. In 2023, the European Defense Fund invested 1.031 billion euros in 54 projects. Among these projects, the modular multi-purpose patrol ship is one of the most important test fields for the feasibility of effective cooperation in this field. This project is a pilot project for the European patrol ship. The European patrol ship project is coordinated by Fincantieri and Naval Group’s joint venture Naviris, involving a consortium of more than 40 companies, with the goal of designing a modern, modular, multi-purpose warship that can perform a variety of tasks from combat to long-range patrols and police activities in future combat environments.

As the first naval system developed since the start of the Russian-Ukrainian conflict, the modular and multi-purpose patrol ship may have some innovative features, including in terms of combat system integration. The project is based on a modular approach to ship design, which should facilitate the integration of systems from different companies and countries. In fact, while the project is undoubtedly an excellent opportunity to cooperate in equipping future ships with common combat systems, its success will ultimately depend on whether a high degree of commonality in navigation and combat systems can be achieved in the modifications of various countries. Some solutions (such as missile systems) are more likely to be shared, thanks to the position of the European Missile Group in a roughly unified European market. In other areas (such as radars and sensors), several participating countries (mainly France and Italy) have proud national industrial enterprises, requiring a cooperative approach that has not been seen since the Italian-French "Horizon" destroyer project. The successful implementation of the project will also require the active development of standards coordination to enhance interoperability in this area.

The Italian companies Leonardo, Fincantieri and other European players (including academic institutions such as the University of Genoa) are collaborating on the development of a European digital ship reference architecture through the "European Digital Navy Foundation" project. To this end, the partners will work to integrate the Joint Naval Operations Cloud into the broader Multi-Domain Operations Cloud, ultimately creating the next generation of smart ships.

Some of the European Defense Fund projects approved in 2022 are closely related to the development of unmanned systems in the naval field. For example, the Sea Space Ground Effect Autonomous Unmanned Aerial Vehicle (SEAWINS) project aims to develop a new military surveillance drone, a new type of aircraft that can fly on the sea surface using ground effect. They are capable of carrying large payloads over long distances in both the sea and air domains. Another project - Hydrogen Battlefield Reconnaissance and Intelligence UAV (HYBRID) - aims to develop a vertical take-off and landing unmanned system for use in a variety of different environments and against a variety of threats.

There is also a call for projects that the European Defense Fund intends to invest in, which aims to study, design, prototype and test a medium-sized semi-autonomous surface vessel capable of carrying different mission modules. These modules can be remotely controlled and will cover anti-submarine warfare, naval mine warfare (MMW) and anti-surface ship combat capabilities.

European Defense Fund’s predecessor projects

Before the creation of the European Defense Fund, its predecessor projects, the Preparatory Action for Defense Research (PADR) and the European Defense Industrial Development Program (EDIDP), also launched related projects in the naval field.

The aforementioned OCEAN 2020 is one of the largest projects funded by the Defense Research Preparation Action: the project, completed in 2021, brought together more than 40 partners under the coordination of Leonardo. OCEAN 2020 successfully achieved its goal: to integrate different systems - ranging from surface ships, helicopters to underwater systems - to achieve the vision of a common maritime architecture. This was achieved through efficient manned-unmanned combinations and effective integration of data from different types of systems, as well as two maritime demonstrations in the Mediterranean and the Baltic Sea. In addition to representing a fruitful result of industrial collaboration among European partners, OCEAN 2020 also demonstrated the importance of maritime surveillance - not only integrating different systems, but also elaborating on the operation plan (CONOPS) communication protocols and data sharing tools.

Also within the framework of the Defense Research Preparation Action, a consortium of four member states is working on the feasibility of using electromagnetic railguns (EMRG) as long-range artillery systems in the context of the "Munitions for Improving Long-Range Strike Effects Using Electromagnetic Railguns" (PILUM) project. The project also studies the possibility of integrating electromagnetic railguns into naval platforms.

As for the European Defense Industry Development Program, the "European Mine Risk Clearance" (MIRACLE) project is committed to contributing to the promotion of European anti-mine missions by improving the main components of standoff mine warfare.

In terms of underwater warfare, the "European Anti-Submarine Warfare Autonomous Networked Innovation and Collaborative Environment" (SEANICE) project aims to develop the next generation of anti-submarine warfare systems based on a combination of manned and unmanned platforms. By adopting the most advanced technology, the "European Anti-Submarine Warfare Autonomous Networked Innovation and Collaborative Environment" will improve the EU’s detection, tracking and identification capabilities.

The "New Earth and Ocean Observation Satellite (NEMOS) project aims to carry out a satellite mission to provide near-real-time monitoring of defense operations involving critical infrastructure on the coastline, sea surface or at sea.

"Survivability, Electronicization, Automation, Detectability, Predictability of European Naval Capabilities in Extreme Conditions" (SEANICE) DEFENCE looks to the future and aims to facilitate the preparation of a technology roadmap for the next generation of naval platforms by carrying out feasibility studies to identify innovative solutions that the EU may need to advance.

The role of the European Defence Agency

In line with the EU’s efforts to counter the risks posed by mines and underwater malicious activities, the European Defence Agency has several projects to strengthen the EU’s preparedness to face these threats, starting with the “European Unmanned Maritime Systems for Mine Countermeasures and Other Naval Applications” (UMS) project.

The UMS project is directly linked to the “Maritime Mine Countermeasures, Next Generation” (MMCM-NG) project, which ended in 2017. The project developed solutions for ships to counter mines and other underwater improvised explosive devices (IEDs) and identified a set of common requirements for EU Member States.

The European Defence Agency recently launched a new project on a bionic underwater vehicle swarm (SABUVIS I), building on an initiative (SABUVIS I) that was completed in 2019. II).

To develop a common maritime picture, several EDA Member States and Norway are involved in the MARSUR project, which aims to improve the dialogue between maritime information systems.

The EDA also carries out a number of Research and Technology (R&T) activities, which are grouped under its Capability Technology Groups (better known as CapTechs). CapTechs aim to identify existing technology gaps in European programmes and identify potential areas for Member States to cooperate.

The EDA has a CapTech Group dedicated to the maritime domain. The Maritime CapTech Group is dedicated to supporting European navies in facing future challenges and encouraging further research to address key gaps in capability requirements identified through the common Strategic Research Agenda (SRA). Research on mine countermeasures is a case in point.

The Capability Technical Group “Missiles and Ammunition” also contributes to the Naval Mobility and Underwater Control priorities listed in the EDA’s Capability Development Priorities. This Capability Technical Group is dedicated to research and development of various technologies related to strengthening and extending EU defence capabilities.

The future of EU cooperation

The EU currently has limited resources to invest in the development of naval combat systems. As in all other environments, the success of EU cooperation in the naval field requires strong collaboration within the EU industrial sector. The EU can rely on an advanced maritime military industry, with some Member States sharing the latest systems and cutting-edge technological capabilities. However, the EU continues to suffer from fragmentation, duplication of efforts and lack of interoperability among national navies.

Going forward, further cooperation between Member States and their industrial sectors in the naval field will be crucial, not only to help achieve higher levels of capability and readiness, but also to achieve more effective interoperability in the EU naval combat field.

Programs such as the modular and multi-role patrol ship have also become important testing grounds in this regard, but meaningful cooperation depends on reaching agreement on the naval combat systems that will be equipped on these ships (and all future European ship designs). Given that the technological challenges facing European navies require levels of investment that are difficult for a single country to afford, the EU has the potential to play an important role in encouraging joint investment in future technologies such as directed energy weapons, artificial intelligence, quantum computing, and hypersonic capabilities. In the long term, the success of such encouragement will depend not only on how much money the EU can invest, but also on ensuring that these funds lead to the rapid development of shared, critical technological solutions.