In recent years, in the face of Russia’s growing land strike capability and anti-access/area denial capabilities, the British Navy may recall the thinking and verification of the near-shore blockade against the German and French navies in the late 19th century. Today, Britain’s dependence on the ocean has increased compared to that year, and forward deployment against Russia is obviously most conducive to maintaining its maritime interests. However, the British Navy at its peak was forced to abandon the near-shore blockade in the early 20th century. Today, the British Navy is no longer able to build according to the "two-power standard", and the fleet size may even shrink further. Faced with this dilemma, the Royal Navy has resorted to modularization, unmanned operations and long-range strikes.

When considering its role in the future combat environment, if the British Navy wants to meet its goal of becoming the most important naval contributor in Europe, it must work hard to cope with a series of interrelated changes in maritime operations. In the near to medium term, the British Navy will face two key challenges:

1. The surge in long-range precision strike capabilities will threaten the freedom of maneuver of ships at sea and the security of critical infrastructure on land;

2. The re-emergence of underwater threats to sea lines of communication and critical national infrastructure.

The British Navy will respond to these challenges with a historically low number of surface ships until the 2030s. Of course, this is a challenge that all of Europe will face, not just the British Navy. However, this is a core mission for the British Navy if the UK is to meet its ambitions described above and project Europe’s leading naval power. Further afield, the British Navy must support a pivot to the Indo-Pacific region, which, while currently limited in ambition and resources, could become a more important pillar of British national security policy in the context of Brexit, with the UK joining the Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for Trans-Pacific Partnership (CPTPP) and participating in strategic partnerships such as the Australia-UK-US Security Partnership (AUKUS). If the above agreement is passed, the UK will operate in a region where the following situation exists: the adversary navy has even more ships than the United States and is supported by a powerful shore-based missile arsenal.

The current vision of the British Navy is to achieve the ambitious goals set by British decision-makers. The key is to use flexibility and lethality to take advantage of more advantages in limited ships. As the Navy Secretary said, the UK will not seek to match the number of ships with its competitors, but will seek to be one step ahead in disruptive future technologies to offset the numerical advantages of its competitors. The realization of this vision depends on the following prerequisites:

1. Improve the modularity of naval combat ships to achieve mission flexibility and rapid adoption of various capabilities;

2. Pay attention to the adoption of unmanned capabilities to make up for the shortage of manned systems;

3. Focus on long-range strikes, giving the British Navy a greater inland strike range.

This is similar in some ways to the vision outlined by the US Navy, although it is much smaller in scale, but more demanding in making up for the problem of limited numbers.

Adversary Challenges

Based on the priorities identified in the Integrated Assessment, the Royal Navy will face two major challenges in the European Theater - this article will focus on the European Theater as this region will take precedence over the Indo-Pacific in the short to medium term.

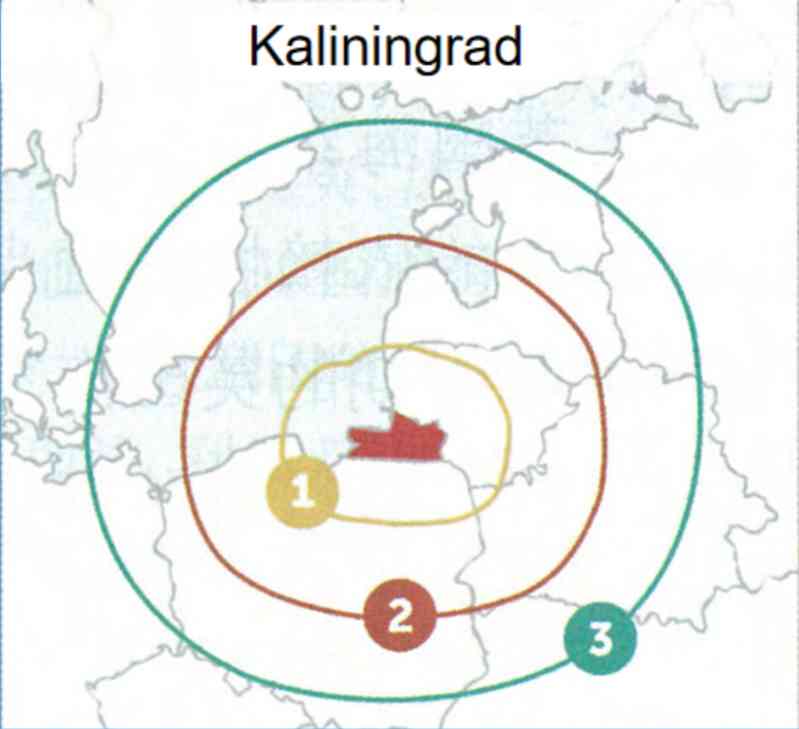

The first challenge is Russia’s anti-access area denial capabilities. Russia has invested in a range of powerful air, sea and ground-launched anti-ship missiles that will form an effective multi-layered defense around the Russian coast. Second, the "caliberization" of the Russian fleet - the introduction of 3M-14 "Caliber" missiles on a range of assets (including the "Thug"-M corvettes) - means that these ships can target key British military and civilian infrastructure from a defensive ring close to the Russian coast. The deployment of hypersonic cruise missiles such as the 3M22 "Zircon" has exacerbated this challenge. Hypersonic missiles significantly shorten the reaction time of air and missile defense capabilities - which poses greater risks to key power projection assets such as aircraft carriers. The relative speed and maneuverability of these missiles make it very difficult to implement traditional "launch-observe-launch" air defense tactics against them, as the warning time is insufficient to complete this cycle. True, Russia’s difficulties in areas such as high-tech manufacturing may limit the number of hypersonic missiles it can deploy, but these missiles still increase the risk of operating near Russia’s defense circle - ships within these defense circles can target critical European infrastructure.

The third challenge that the British Navy will face is the re-emergence of underwater threats, which stems from Russia’s latest capabilities, such as the "Yasen M" class submarines, which are smaller than their Soviet-era predecessors but are as quiet as Western submarines. In addition to traditional underwater threats to naval formations and sea lines of communication, special submarines used by Russia’s Main Directorate for Deep Sea Research (GUGI) may need to be considered. GUGI’s submarines include specialized submarines such as the AS-12/AS31 "Лowapuk", which have titanium hulls and can dive to extreme depths. These submarines may be used to destroy underwater cables that most Western economies rely on - both an asymmetric subthreshold response to economic sanctions and a means of coercion in wartime. The need to protect critical underwater infrastructure has driven the plan to purchase two multi-purpose surveillance ships. These planned ships are likely to have relatively small crews and will serve as platforms for unmanned systems equipped with a variety of sensors. In wartime, the most feasible way to contain underwater challenges has historically been forward defense. A reactive posture cedes the initiative to the adversary, while a forward posture creates difficulties for the adversary and can limit its freedom of maneuver. Establishing forward positions in areas such as the Barents Sea to gain the operational initiative to contain this threat will be critical. However, this puts ships and aircraft within striking distance of various anti-access capabilities—making the ability to secure entry points to a combat zone a top priority.

NATO navies (including the British Navy) face a paradox. On the one hand, Russia’s anti-access capabilities force them to keep their distance, while on the other hand, their forward deployment capabilities become more important, which is to achieve joint operations and eliminate the threat of precision strikes from the sea.

The British Navy’s future development vision

The literature on adaptability tends to subdivide the development process into exploration and exploitation. It should be reasonable to say that the British Navy is still focused on the exploration stage and is creating conditions for future development. The Defense Guidance Document and subsequent statements by several key figures set several core goals for the US Navy’s vision. First, the British Navy will attach importance to modularity in shipbuilding to make up for the lack of quantity. The basis of this approach is the concept of a multi-role force - the ability to change its composition and functions in the short term. The hull design of ships such as the Type 31 frigate is based on this principle. The same is true for the Type 32 frigate announced in the Defense Guidance Document. The purpose of these ships is to switch mission modules, allowing a limited number of surface ships to perform multiple functions.

This design principle also includes a second core function-rapid integration of unmanned capabilities. Ships such as the Type 32 frigate are expected to be interoperable with unmanned assets and be able to carry, launch and recover these assets. This will be crucial to achieving a distributed force that can operate in an enemy anti-access "bubble" at a sufficient scale. Unmanned assets are also envisaged to increase fleet size and sensors in the underwater domain, and the potential for distributed sensor networks on assets such as underwater gliders has also been noted. Currently, the Royal Navy is trialling MANTA - a £2.4 million programme that will deliver a very large unmanned underwater vehicle capable of deploying a range of payloads, including smaller unmanned underwater vehicles and mines. This will be important given that the number of manned attack submarines in the Royal Navy is unlikely to increase. High-precision underwater sensor networks are seen as a potential countermeasure to increasingly quiet enemy submarines, and unmanned long-endurance capabilities will be an important part of these networks. The third component of the Royal Navy’s vision for future lethality is greater range and speed. Current Admiral Ben Key has expressed ambitions to introduce hypersonic weapons in the Royal Navy, and the UK is currently seeking channels for collaborative development of these capabilities through the AUKUS partnership. Hypersonic weapons require large launch platforms, which in principle could be on the Royal Navy’s planned future Type 83 destroyers or SSN(R) submarines.

However, the British Navy is not currently committed to the immediate deployment of various systems that can achieve lethality and survivability. As for the killing of surface ships, the British Navy will seek to use Norway’s Naval Strike Missile (NSM) as an interim solution while focusing on the long-term effort to deliver its future cruise/anti-ship weapons - a joint British-French project that has invested £95 million. The project is likely to deliver products in the 2030s. Although the British Navy is working to test and adopt autonomous systems through its NavyX accelerator, unmanned systems have not yet been purchased on a large scale. This may reflect the Royal Navy’s desire to acquire mature systems to meet the goal of distributed operations, while preparing platforms that can carry these unmanned systems. The first generation of unmanned capabilities adopted by the Royal Navy may meet more limited goals - freeing personnel from labor-intensive tasks - rather than performing ISR or combat missions. In fact, the Royal Navy’s first unmanned capabilities were to replace its mine countermeasures ships with unmanned systems. In addition, trials using unmanned vertical take-off and landing systems such as Leonardo’s Proteus (a project funded by the Defense Autonomy and Security Accelerator [DASA] with an investment of up to £60 million) can support some ISR functions, including close-range anti-submarine warfare.

Future unmanned capabilities - especially vertical take-off and landing drones - may play an important role in anti-submarine warfare and littoral mobility concepts. They will become part of the capabilities currently built around the Merlin MK 2/2a anti-submarine helicopter, Mk 4/4a and the Wildcat helicopter (affiliated to the assault helicopter unit to support littoral mobility). The former is part of the Merlin life extension program, using new avionics and folding rotors to adapt the Merlin MK3 to maritime missions. The retirement of the Merlin will be delayed from 2030 to 2040, which means the Royal Navy will rely mainly on traditional manned vertical take-off and landing assets.

The British Navy is also committed to improving the survivability of large platforms in a competitive environment. It will upgrade its Type 45 destroyers to enable them to intercept ballistic missiles-mainly to deal with anti-ship ballistic missile threats. "Aster" 30Block1NT will be the ballistic missile defense solution pursued by the UK. The Royal Navy is also testing the Dragonfire directed energy system, a 50-kilowatt directed energy weapon that can be used when ships are confronting missiles and drones, and the UK Ministry of Defense plans to spend up to £130 million on the project. In addition, the Royal Navy is working hard to improve the capabilities of various systems, including operators, to respond to rapidly changing threats. One example of this investment is the artificial intelligence-driven STARTLE system that was tested on Type 45 destroyers and Type 23 frigates during the Formidable Shield exercise held west of the Hebrides in 2021. The goal of the system is to reduce the burden on operators in air defense.

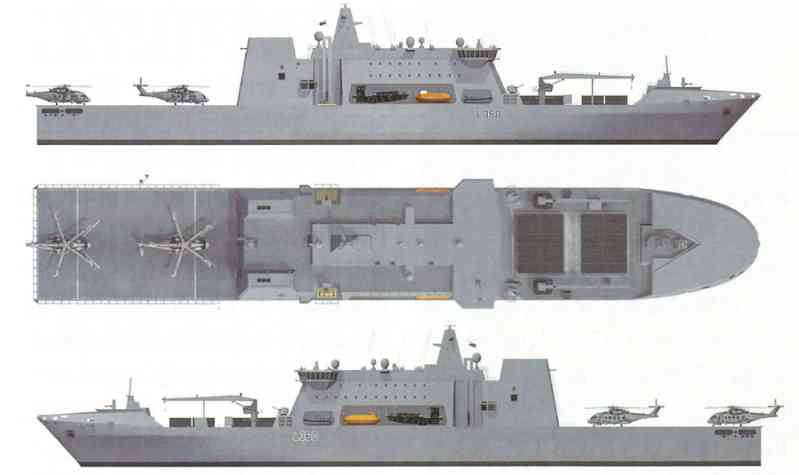

In the littoral space, the Royal Marines may become a force suitable for assault missions. Crucial to this is the ability to use tactical firepower, such as loitering munitions, and connectors to achieve close-range penetration. The planned future assault force will be supported by a multi-mission support ship, a multi-purpose ship designed to support maritime continuous operations and tasks such as maritime penetration and C2. This will form the backbone of the UK’s planned littoral strike group. Under this force employment scheme, commandos will be used to disrupt anti-access "bubbles" to pave the way for larger forces (such as the US Marine Expeditionary Unit) to take action. The guiding principle is that despite its shrinking size, commandos can still act as a distributed force, operating within the anti-access/area denial "bubbles" formed in the early stages of a conflict, play an important attack role, and disrupt the failure points that the opponent’s integrated and complex systems rely on.

Conclusion

The envisioned British Navy will be a force that can add special capabilities to the alliance. Although it cannot be equipped with as many manned assets as before, it hopes to ensure access capabilities through means such as rapid strikes, distributed operations, and raids to increase lethality. It also attempts to make up for the lack of scale through a distributed lethality approach similar to the US Navy. To achieve this vision, it must attach great importance to augmenting manned platforms with a large number of unmanned capabilities and become a navy that can provide specific exclusive capabilities (such as entering littoral competition areas, maritime ballistic missile defense, and rapid strikes).

Unlike the US Navy, which has already committed to acquiring a limited number of unmanned capabilities and retiring legacy assets, the Royal Navy cannot commit to procurement immediately. For now, its main focus is on creating the conditions for this transition through experimentation, generating flexible future capabilities and establishing an information architecture that can support a distributed force. This is reasonable given the inefficiency of adopting new technologies before they are ready for use, but the Royal Navy’s key challenge will be to ensure that the acquisition of key capabilities at scale is not delayed for a long time. As the Russia-Ukraine conflict has demonstrated, high-intensity operations cost a lot of resources - both sides have already consumed more than Western countries have in stock in some capabilities. Building up stocks of key capabilities, both on the ground and at sea, takes time - which also means that the necessary exploration phase cannot last too long.