In the second half of the 19th century, the European adventure craze had not subsided, the colonial era of the great powers was at its peak, and the hinterland of the African continent became the last world that few "civilized people" had set foot in. One after another, European expeditions went deep into Africa to explore the mystery and the unknown, and to expand the territory for the colonial empire. European explorers encountered fierce and brave black warrior tribes on the vast East African grasslands and dense mountain jungles. These tribes each had strange customs and warlike traditions, and they made European whites suffer a lot in the fierce conflict between "barbarism" and "civilization".

The last goal of the colonists in Africa-East Africa

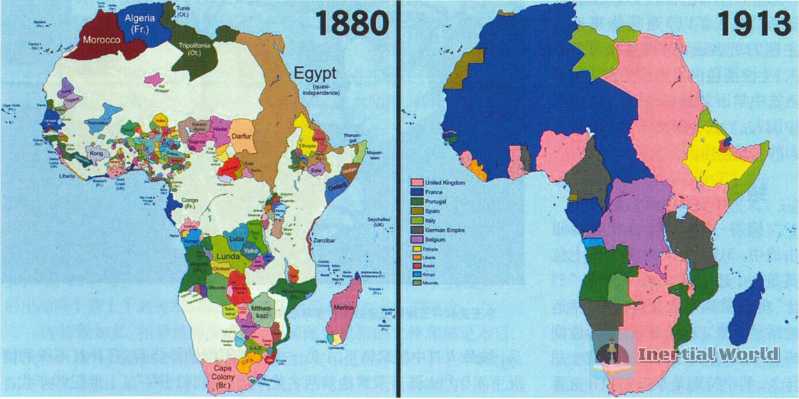

In the era of great colonialism in Africa, the two great powers of Britain and France each funded expeditions, starting from exploring the source of the four major African rivers, the Nile River, the Zambezi River, the Congo River, and the Niger River, and continued to go deep into the inland. At that time, Britain advanced from the north and south along the line of Egypt-Sudan and South Africa-Rhodesia (now Zimbabwe and Zambia), while France advanced from the east and west along the line of French Sudan (now Senegal and Mali) and Djibouti. In the end, Britain was one step ahead and established British East African colonies including present-day Uganda, Kenya, and Zanzibar, Tanzania. As for the emerging competitor, the Second German Empire, it established a huge German East Africa at its peak. It is mainly based on Tanganyika (part of the Tanzanian mainland), basically including present-day Rwanda, Burundi and northern Mozambique, with a total area of nearly 1 million square kilometers (of which Tanganyika is nearly 940,000 square kilometers), almost three times the area of Germany today. It was not until the 1960s that Africa set off a wave of independence, and the colonial system of the great powers finally collapsed. Of course, this article is not concerned with the process of the establishment and maintenance of the African colonial system of the great powers, but the opponents of the colonizers in this process-the tribal warriors in East Africa.

The indigenous black tribes in East Africa often clashed with each other. Economic motives are very important, and the purpose of the conflicts is mostly to steal cattle. Cattle are the only valuable movable property in East Africa. The economic strength of almost all tribes in East Africa is measured by cattle, especially the famous Masai. Frederick Lugard, an important British colonial official in Uganda in the late 19th century (it is worth mentioning that this Lugard served as the British Governor of Hong Kong from 1907 to 1912. Hong Kong translated his Chinese name as "Lugi", and "Lugi Road" on the Peak of Hong Kong Island is still named after him) once wrote that every piece of land in East Africa was ruled by a "brutal and unbearable tribe". Africans are "brutal" for survival, which is incomparable to the Europeans who came to colonize from afar with "brutalism" as a means.

Maasai, the king of the grassland

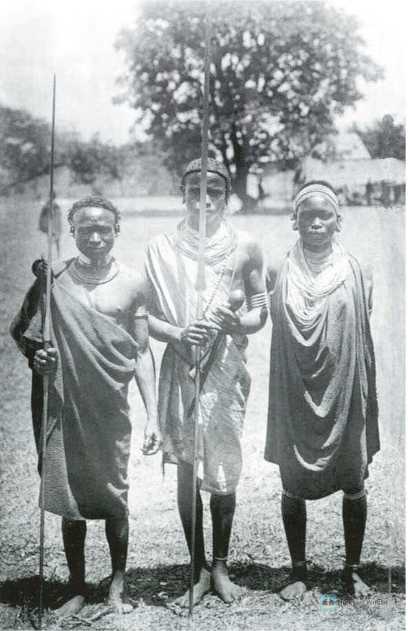

First, let’s talk about the Maasai, who have been known to the outside world for many years because of the documentary "Into Africa" and are believed to run every day to chase antelopes and hunt lions with spears. About 300 years ago, the Maasai migrated from northern Africa to the East African savannah. They conquered or drove away the ancient indigenous people of East Africa, occupied the main pastures of today’s Kenyan plateau, and expanded their territory southward to today’s Tanzania. It is generally believed that the Maasai are mainly divided into two categories. One is the traditional Maasai, and the other is the Kwavi. Kwavi usually refers to those Maasai who have lost their cattle and livestock and are forced to engage in farming. In fact, the Maasai can be divided into sixteen major tribes, which constitute a loose and semi-permanent armed group.

The sixteen Maasai tribes both fought against each other and united to fight other tribes. The war was mainly for cattle. In the myths and legends of the Maasai, God initially gave all the cattle in the world to the Maasai, and later all the cattle in other people’s hands were stolen from the Maasai. Therefore, the Maasai robbed cattle not only for survival, but also for the mission of faith. As a result, the Maasai’s footprints of robbing cattle spread all over East Africa.

Like most tribes in northern East Africa, the Maasai’s military organization system is based on age groups. Every seven years, the Maasai will hold a ceremony, and all young people will join the military group and undergo training. At about 20 years old, these young people will be organized into "Moran", which means "warrior". Herding cattle, which the Maasai rely on for survival, is not a heavy physical work, and can be easily supported by teenagers and the elderly. Therefore, the Maasai at the warrior age can leave their jobs and engage in economic production activities, fighting for the tribe wholeheartedly for up to 15 years. The "Moran" warriors are stationed in their own barracks, and usually eat beef, cow blood, milk and other foods that are believed to strengthen the body. Young warriors were not allowed to marry, drink, smoke or eat vegetables, and some prohibitions were relaxed for young warriors. The Maasai also used other methods to boost the courage of the warriors, such as drinking a brewed liquid. This brew is made of tree bark and herbs. It is taken before going into battle. It is said to be as effective as amphetamines and marijuana, allowing people to forget fear and tirelessness in battle. The Maasai often used a tactic in fierce battles, which was to have the bravest warriors line up in a wedge shape in the center of the array, supported and covered by the guards and the flankers on both wings, and charge directly at the enemy array. This formation is called "Eagle Wing". Unlike other African tribes, the Maasai did not use war drums or other musical instruments in battle, but only sang war songs and shouted loudly.

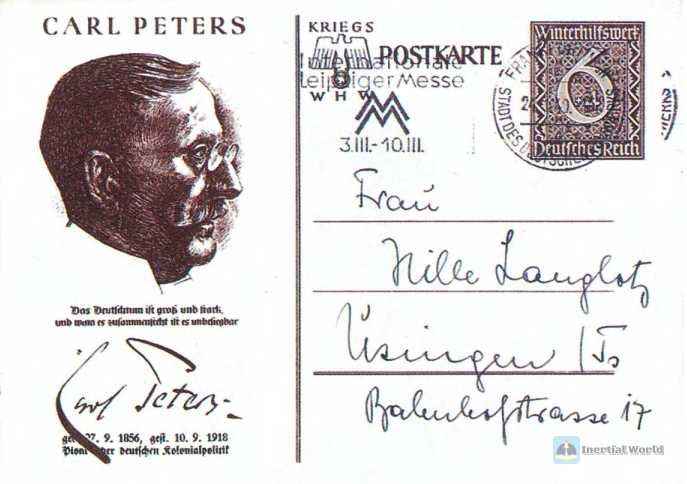

At first, the enemies of the Maasai were not the white Europeans, but the Arab caravans from Zanzibar. As we all know, Zanzibar is located on the coast of East Africa, that is, the part of Tanzania outside the African continent today, and consists of dozens of islands. In the 19th century, Omanis from the Arabian Peninsula sailed here and established the Sultanate of Zanzibar. Successive Zanzibar sultans controlled clove plantations and supported Arab caravans to go deep into the interior and transport ivory and slaves. The clove, ivory and slave trade brought prosperity to Zanzibar until the end of the 19th century when Zanzibar fell under British colonial rule. At that time, these Arabs felt that the muskets in their hands were enough to scare the black indigenous tribes, so they often looted Maasai villages along the caravans and took away women. Who knew that in 1857, 800 Maasai "Molan" warriors defeated 148 Arabs and Baluchi (Baluchi, a general term for the Iranian-speaking people from the Indo-European language family of the Arabian Peninsula) musketeers. It is said that facing the first wave of enemy volleys, the Maasai fled in all directions. The Arabs rushed up to round up the Maasai’s cattle, but the Maasai came back and surrounded the Arabs in turn. The Maasai had already understood that it took a long time to reload a musket. They fled in all directions on the surface, but in fact they lured the enemy to lose their composure. From then on, the Maasai repeated the same trick again and again, and always won a great victory. Soon white explorers heard that the road from the coast to Lake Victoria was blocked because there were Maasai on the road. At first, some people suspected that the Arabs deliberately exaggerated the risks to protect their lucrative slave and ivory trade. But in 1877, the German explorer and naturalist Hildebrandt submitted a report to the Berlin Geographical Society, saying that he was invited to join a caravan and travel to Lake Victoria with more than 2,000 Arabs. At that time, he declined, but later he was very lucky: "A year later, I heard that the caravan was attacked by the Maasai, and only a few survived." In the same year, Hildebrand still plucked up the courage to join an Arab caravan, but he was forced to turn back three days after setting out, because "shortly before I arrived, they (Maasai) slaughtered this caravan of 1,500 fully armed people". Karpides, a famous German explorer, colonist and politician in the late 19th century, even recorded that in 1887, the Maasai "killed a total of 2,000 Arab caravans without leaving a single one alive, and arranged all the corpses one by one in neat rows and columns, and put each Arab’s gun on the shoulder of the corpse with ridicule and contempt".

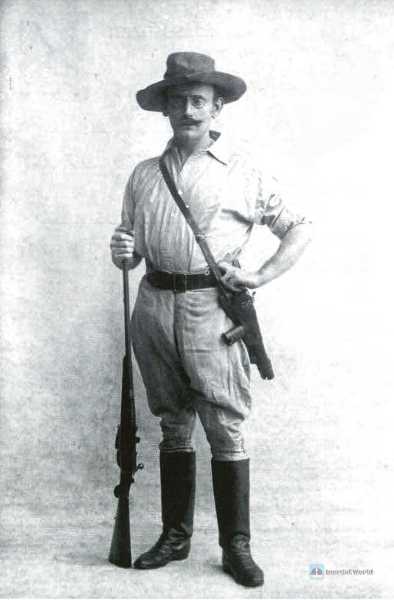

In 1883, Scottish geographer and explorer Joseph Thomson successfully crossed the Maasai territory for the first time. Along the way, Thomson encountered several groups of Maasai warriors who asked him for "gifts" and showed no fear of white weapons. In 1889, the German Karpides led the European white expedition team and had the first direct conflict with the Maasai. At that time, Karpides commanded the famous "German Emin Pasha Relief Expedition" (German Emin Pasha Relief Expedition), which was one of the most important European expeditions in the interior of Africa in the late 19th century. It was nominally to rescue the trapped Emin Pasha. Emin Pasha was a Jew of Ottoman and German descent, with multiple identities such as German doctor, explorer and Egyptian official. He served as a military doctor and local administrator of the Ottoman Empire, so he took a Turkish name. In 1876, he also served as a military doctor for the army under the command of the famous British Governor Gordon in Khartoum, the capital of Sudan. Emin Pasha was a diligent researcher who made great contributions to the Europeans’ knowledge of Africa’s geography, natural history, anthropology and linguistics. At the time, he was the governor of the Upper Nile Equatorial Guinea Province appointed by Egypt, and was under siege by the Mahdi Revolt of Sudan.

(German Emin Pasha Relief Expedition), this was one of the most important European expeditions in the interior of Africa in the late 19th century, nominally to rescue the trapped Emin Pasha. Emin Pasha was a Jew of Ottoman and German descent, with multiple identities such as German doctor, explorer and Egyptian official. He served as a military doctor and local administrator in the Ottoman Empire, so he took a Turkish name. In 1876, he also served as a military doctor for the army under the command of the famous British Governor Gordon in Khartoum, the capital of Sudan. Emin Pasha was diligent in research and made great contributions to Europeans’ understanding of Africa’s geography, natural history, anthropology and linguistics. At that time, he was the governor of the Upper Nile Equatorial Guinea Province appointed by Egypt, and was besieged because of the Mahdi uprising in Sudan.

Pedes’ expedition crossed the Maasai territory to Uganda. There were two white men and 21 Somali African native soldiers (the so-called Askari, transliterated as “Ascari”) in the expedition. Of these 21 men, nine were equipped with repeating rifles. There were also 85 porters, who were also armed. Pedes decided to take the initiative to provoke a conflict with the Maasai. He refused to make overtures to the Maasai and plundered them for food and livestock to supplement their insufficient supplies. On a cold morning in December, Pedes attacked a Maasai mountaintop village in Elbejet. Most of the Maasai were still asleep at the time, but a sentry discovered the attacker. The sentry took the initiative to attack the attacker and was shot down. The gunshot woke up the villagers. Women and children fled down the hillside to hide, while the men rushed out of the village to fight back. The Maasai went around the mountain and threatened Pieddes’ camp, forcing Pieddes to withdraw from the village. Pieddes gathered his men and defended the camp with all his strength. With less and less ammunition, Pieddes had to order a breakout and retreat to the nearby jungle.

Soon after the expedition retreated, they saw hundreds of Maasai approaching. Pieddes thought to himself that these tribesmen had never seen a repeating rifle, "they would think it was a supernatural power at first sight." Sure enough, facing the rifle fire, the Maasai warriors stopped several times in a row, which gave Peters’s men time to reload their guns. However, the Maasai learned quickly and turned to short charges, rushing from one tree to another, "always being careful and using cover to avoid bullets." Carl Peters described: "Faced with the first round of shooting, the Maasai knew how to protect themselves. They either crawled on the ground or hid behind a tree. Before the rifle was reloaded for the second round of shooting, the Maasai had already approached and thrown their spears, killing their opponents... In general, as soon as the expedition opened fire, the Maasai immediately fled. Once they stopped, the Maasai massacre began. The agile Maasai would kill the enemy in an orderly manner."

At the same time, the rear guard of the expedition was also attacked. Fortunately, the rear guard held on, and the armed porters had time to join the front line and support the rear guard. Finally, the Maasai retreated, leaving behind 43 bodies. Pieddes lost 7 men and most of his ammunition was used up. Next, Pieddes fought and scattered, and a large number of Maasai warriors followed him all the time. Two days later, the Maasai raided the camp at night. A row of signal rockets were fired, and the Maasai were driven out of the camp. However, this row of rockets failed to break the morale of the Maasai as expected, but only allowed Pieddes’ men to use enough light to open fire. Finally, the expedition finally arrived safely at the Arab trading post of Kamasia.

The result of Peters’ retreat was quite good, and he also brought back some cattle as trophies. It is generally believed that this was probably due to the Maasai people’s encounter with cattle plague, which greatly damaged their vitality. The cattle plague may have been transmitted by the white people. On the way back from Elbergat, the expedition passed countless cattle pens, all of which were empty. Peters found that many areas that were densely populated when Thomson passed through were now deserted. If Peters had dared to attack the Maasai in this way a few years ago, his expedition team would probably have been killed without a single piece of armor left. As for Emin Pasha, he was later discovered and rescued by an expedition led by the famous British explorer Stanley. Emin Pasha did not leave Africa, but instead served the German East African Company and continued to explore the interior of Africa. In 1892, he died at the hands of Arab slave traders in the Congo Free State.

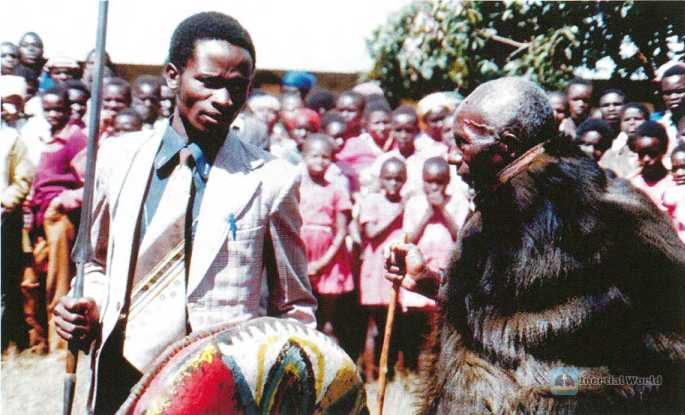

By the early 1890s, the Maasai had regained their strength, but publicly declared that they were unwilling to be enemies of the white people. The East African Company, a colonial administration established by the British, had constant conflicts with the Maasai, but there had been no large-scale conflicts between the Maasai and the British. The Maasai ignored the chaos of the great powers that swept East Africa and kept their distance. The Arabs always avoided the Maasai, and the white explorers also respected them. The British often recruited the Maasai to serve as colonial troops or auxiliary forces to help them fight. The Maasai regarded themselves as allies of the British colonial authorities, not subjects of the mother country. To this day, the ancient war marks on the Maasai have never been erased.

The brave and warlike Nandi people

In addition to the Maasai, there are also the Nandi people. Mount Elgon in northern Kenya is the second highest mountain in Kenya. It is located at the border between Kenya and Uganda. The surrounding jungle is dense, and the Nandi people live in the mountains. The Nandi people call themselves "Chemwal", which means "cattle raiders". The word "Wa-nandi" was originally a Swahili insult to them, meaning "cormorant", implying their greedy plunder. The Swahili are a black race living in coastal areas of East Africa such as Zanzibar. They are distant descendants of long-term mixed blood of blacks and Arabs, Persians, Southeast Asians, South Asians, etc. They believe in Islam and engage in slave trade with Arabs in the Sultanate of Zanzibar. The Nandi people never do business with Swahili caravans, and they attack them when they see them, so the two sides become enemies. "Kapchumba" is a common place name in the Nandi tribe, meaning "the land of the Swahili." It is said that this name was given because these places are the burial places of foreigners who were lured there and ambushed and slaughtered.

The Nandi tribe is not large, with a total of no more than 5,000 warriors. The number of people sent out for each battle is far less than this, but it is well-known. It is said that only the Maasai dare to confront the Nandi head-on. The traditional form of warfare of the Nandi people is to send small-scale troops to plunder cattle and abduct people. The Nandi people do not keep slaves. They usually redeem captured captives with cattle, but Maasai captives are sometimes naturalized into the Nandi tribe. Like the Maasai, the Nandi people are organized into age groups, and full-time warriors come from the group of young people. Every seven years, the Nandi people hold a ceremony in which the sacred responsibility of defending the safety of the tribe is passed from one generation to the next. According to tradition, the Nandi people must obtain the permission of the chief to go out for looting. Then, the Nandi people will blow the horn and summon the warriors. The symbol of the chief’s authority is a long stick, which has been cast by the chief himself. When the Nandi warriors go to war, they will have someone hold this long stick high and walk at the front of the team. The Nandi people firmly believe that the chief can cast a spell to separate his head from his body and let his head fly to the battlefield to observe the performance of the warriors.

The Nandi tribe can be divided into 17 tribes, each of which uses an animal as a totem and plays a specific military role. For example, the lion tribe is responsible for the right wing of the army in battle, and the hyena tribe is responsible for the rear guard during the retreat, as well as setting ambushes along the way in the jungle. The Nandi people like to go to war in the dry season. Every year, the dry season starts in October, and the Nandi people will rush 100 miles away to start looting, so the Nandi people are all famous long-distance runners. The Nandi people will first send out scouts (scouts) to determine the location of the enemy village and repeatedly scout the route of attack and retreat. After the scouts come back, the Nandi people gather the main force of the team and quietly move towards the target. The Nandi people lurk near the target village and wait until dark to launch an attack. When attacking, the team is divided into three parts: the first part is responsible for feinting, and the second part is responsible for rushing into the cattle pen to steal cattle. The surrounding tribes are afraid of the Nandi people’s robbery, and they have locked their livestock in pens with thorn fences or mud walls for protection. The Nandi people have to destroy the fences or mud walls before they can steal cattle, which is equivalent to alerting the enemy. But the Nandi people are not afraid, because they are openly robbing. After the battle, the first part covered the retreat, while the third part, composed of the youngest and most inexperienced fighters, was responsible for driving the cattle.

In the 1890s, the Nandi people began to steal the telegraph wires erected by the British colonial authorities along the border. The Nandi people did this mainly because the wires were rare and they had to cut them back to give them as ornaments for women. Later, the Nandi people stole the heavy metal spikes used to protect the rails on the Uganda Railway. They dismantled the spikes and used them as weapons. In 1895, the British sent an expedition to invade the Nandi territory with the intention of catching all the Nandi cattle. As a result, Lieutenant Seymour Vandeleur’s expedition encountered the Nandi people on the banks of the Kimonde River and immediately started a war. The soldiers in Vandeleur’s company were all Sudanese, and the entire company was attacked by more than 500 Nandi warriors. At that time, the Mahdi uprising blocked the road in Central Africa, and the local Egyptian garrison composed of Sudanese soldiers turned to serve the British. These Sudanese soldiers had not received supplies for several years. They wore a mixture of tattered uniforms and local indigenous clothes, and barely wore red Fitz caps on their heads. They were temporarily equipped with new rifles issued by the British. Vandeleur later recalled, "(The Nandi) were obviously well-organized, and they formed a square array on three sides. The long-bladed spears were cold and dense like a jungle, and the spearheads shone coldly in the sun." At the command, the Nandi warriors launched a charge and wiped out a small team composed of 14 Sudanese soldiers in one fell swoop. They then rushed to only 30 yards in front of the main array of Sudanese soldiers before being repelled by the firepower of Martini-Henry rifles and Maxim machine guns.

Vanderle said that fortunately the two sides were facing each other. If he had been attacked by the Nandi during the march, the whole army would have been wiped out. "This charge is a very valuable discovery for us... The Nandi have long been known for their warlike nature... After this battle, we have truly learned our lesson." The Nandi learned from this failure and attacked the British camp at night two days later. They made their way to the outside of the thorn fence surrounding the camp, but they were unable to climb over the fence in the face of the rifle fire of the defenders and were repelled again. Next, the Nandi no longer launched attacks, but just harassed the British like a shadow, intercepted and killed those who straggled, ambushed the British on the road they had to pass, and pushed rocks down from the mountain. The British burned several villages, drove away the cattle, and claimed to have cleared the area. But the Nandi never stopped the conflict with the British. The British admitted that the Nandi was the most difficult opponent they had encountered in Kenya.

The strong and fierce Ngoni people

In East Africa, there were many opponents who confronted the German colonists head-on, such as the Ngoni. The Ngoni originally lived in southern Africa and were the northern neighbors of the Zulus. In the 1820s, the Ngoni were defeated by Shaka, the founder of the Zulu Kingdom in South Africa and known as the "Napoleon of Africa", and were driven to the north to today’s Mozambique. Most of the Ngoni settled there, while some continued to migrate north, crossing the Zambezi River in 1835 and continuing to move north along the banks of Lake Nyasa (also known as Lake Malawi). The Ngoni’s tactics were influenced by the Zulus, and they were strong and fierce. No tribe along the way was a match for the Ngoni. Eventually, the Ngoni tribes settled on the south, west and north shores of Lake Tanganyika and established a series of small kingdoms.

These Ngoni tribes continued to harass the nearby black tribes, making those tribes with poor fighting power miserable. For example, the Tuta, or Watuta, one of the Ngoni tribes, had been migrating further north and arrived at the southern shore of Lake Victoria in the early 1850s. According to the British explorer Richard Francis Burton (a legendary British explorer in the late 19th century who traveled throughout Asia, Africa and America, and was also a geographer, writer, translator, poet, soldier, orientalist, cartographer, linguist, diplomat, spy, fencer and other multiple roles, and it is said that he mastered 29 languages on three continents), the Tuta people were first invited to enter here to help the local chiefs deal with hostile tribes. Who knew that after the battle, the invaders simply became ferocious in the southern shore of Lake Victoria, and were addicted to burning, killing and looting, and robbed cattle everywhere. In the end, the Tuta people eventually formed a semi-nomadic lifestyle, living on cattle from other tribes. As they continued to plunder villages and intercept passing caravans, the Tuta people’s strength gradually expanded. Every time the Tuta people went out to plunder, there were thousands of them. If they failed to capture a village at once, they could besiege it for months. In 1876, the famous British explorer Henry Stanley discovered that the eastern shore of Lake Tanganyika had become a barren land after repeated devastation, and all the surrounding tribes hated these bandits.

There was nothing they could do about it, as the Ngoni people inherited a very strong military tradition from their homeland. The Ngoni tribe also maintained the military organization system of the Zulus, that is, the warriors were divided according to age, and the combat units were formed according to the region. Burton once left a record: "They (the Tuta people) numbered in the thousands, marching in four or five long lines, trying to attack the enemy in an encircling manner. They never shouted or uttered war cries, and they would not be distracted in battle. They used iron whistles to send out necessary signals." "In battle, the Sultan, or the chief, used a brass stool as a token. He sat on the stool, surrounded by forty or fifty elders, in the back row of the array. The chief’s authority was in name only, and the tribe was proud of its independence. The Watuta people rarely fled from the battlefield, and they were never vague about the sword and fire."

At that time, other East African tribes only knew traditional fighting methods - keeping a distance and throwing spears when fighting. The Ngoni people learned close combat from the Zulus early on. They used the Zulu’s short Iklwa, or stabbing spear. The Ngoni marched slowly to the battlefield, sending out scouts in all directions; the warriors’ own young men and women carried food and water to accompany the march; and the army selected warriors to form a separate group to protect the logistics supply. When approaching the enemy’s village, the warriors sat down to recuperate while the chiefs scouted the enemy. The warriors smoked marijuana, which "put the warriors into a state of madness and made their hearts fearless." Even if the enemy noticed the Ngoni, they would not be able to prepare for battle for a while: "Drums would be heard from the fences of the enemy’s village, announcing that the enemy was furious. But the Ngoni still sat on the ground to recuperate, treating the enemy as nothing."

Finally, the Ngoni chieftain ordered the warriors to take up their weapons and dance the war dance. The tribes lined up and blew their horns. The enemy’s drums were drowned out by the sound of the Ngoni horns. Finally, the order was given: "Buffaloes, fight!" So all the warriors rushed over the village fence and competed to be the first to kill into the enemy village. This not only won them great prestige, but also allowed them to be the first to pick the looted livestock. Night raids were also a common tactic of the Ngoni people. In the dark, the opponents were often completely frightened and dared not resist at all, so they could only surrender and be killed. "A large number of Ngoni people rushed to the lakeside and suddenly attacked the Kayuni village. They quietly entered the village, each warrior guarding the door of a hut and ordering everyone in the house to come out. The adult men and underage boys were separated as soon as they came out, and all the women were abducted." Many tribes living along the lake were forced to build stilt houses in the lake for fear of such a surprise attack.

Such a strong warrior tribe, unfortunately, still lost to the Germans. At the end of the 19th century, the Ngoni tribes in Tanganyika fell under German rule one after another. The Ngoni people had fought fiercely with the German expedition in southern East Africa, but eventually surrendered. Songea in southern Tanganyika, the capital of the Rovuma region of Tanzania today, always resisted. The Germans lured the local chiefs to come out for negotiations with a flag of truce, and captured them all in one fell swoop, and Songea fell. Until the Maji Maji uprising in 1905, the Ngoni did not make any fierce resistance to retaliate for this betrayal.

The reason why they could not compete with the Germans was naturally the gap in science and technology. The caravans that the Ngoni often robbed, as mentioned above, also came from Zanzibar. At that time, the cultural and scientific and technological development level of the Zanzibar Sultanate was still higher than that of the black tribes in East Africa, and the most obvious sign was the possession of muskets. Richard Burton recorded that the Tuta people were very cautious about firearms. When they encountered a team led by the red Zanzibar flag, they "quickly broke camp and fled without delaying for a moment." Because the Tuta people knew that such flags would be followed by Arab soldiers with guns.

But the Germans disagreed. German businessman Carl Wiese once encountered a 400-man Arab caravan of Ngoni people who were out robbing in northern Mozambique. According to his description, the Ngoni soldiers were divided into three groups. The first group, composed of teenagers between the ages of 14 and 18, led the charge against the Arabs. The Arabs fired a volley of shots with their muzzle-loading rifles, and the young warriors turned and fled. The Arabs were unprepared for the fleeing black teenagers, and boldly chased them without stopping to reload. As a result, the other two groups of young and middle-aged Ngoni warriors waited for them and ambushed the Arabs. The young warriors turned around and fought again, and the Arabs were immediately surrounded. Most of the Ngoni casualties were teenagers, while almost all the Arabs died in the battle. The caravan leader who escaped by chance later committed suicide in shame.

The indomitable Hehe people

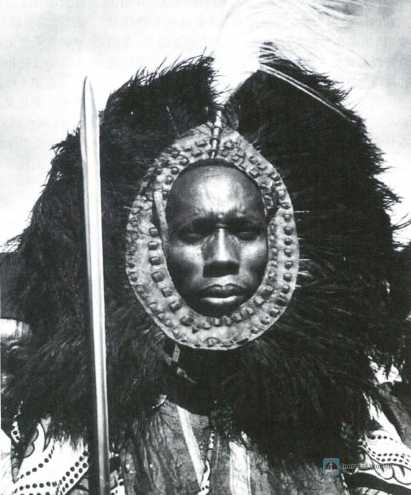

The Hehe people left a deeper impression on the Germans. The so-called Hehe people are an alliance of about 30 small tribes living on and around the Iringa Plateau in southern Tanzania today. The name "Hehe" was first seen in the 1860s, and is said to come from their war cry: "Hee! Hee! Vatavagu twihoma! Ehee!" The outstanding leaders of the Hehe people, Munyigumba and his son Mkwawa, integrated these scattered tribes. Before the German colonial era, the military strength of the Hehe people in East Africa was second to none, even above the Ngoni people. In the late 1970s, Munyigumba led the Hehe people to defeat the Ngoni people. To this day, local folk narrative poems in East Africa still praise this battle. Soon after, Munyigumba died. After a bloody tribal civil war, his son Mukwawa inherited the position of chief. Unfortunately, Mukwawa continued to attack from all sides and plunder everywhere. Due to the attacks of the Hehe people on Arab caravans and the sharp decline in the population of the villages along the way where the caravans relied for supplies, the trade route from Zanzibar to the interior of East Africa was almost interrupted. In 1887, in order to further consolidate his power, Mukowawa moved the ruling center to a newly built stone fortress in the mountains of Kalenga.

According to German estimates, the total population of the Hehe people was about 50,000. The kingdom of Menyigomba included at least 15 formerly independent chiefdoms, and each chief either swore allegiance to Menyigomba or was replaced by someone appointed by Menyigomba. In the event of war, all unmarried men among the Hehe people were conscripted into the army, and these chiefs each sent troops to fight. It is generally believed that the Hehe people also borrowed the shields and piercing spears of the Zulu people and imitated the Zulu people to establish a military organization. Soldiers were divided into age groups and were prohibited from marrying before they could prove themselves on the battlefield. Those who performed well on the battlefield would be rewarded with clothing, slaves and livestock, while cowards who retreated from the battlefield would be forced to serve as porters and suffer humiliation. The Hehe people had good logistics and could go out to fight in both the rainy and dry seasons, often taking care of several battlefields at the same time. A few days before the Hehe people set out, they would first send out scouts, and then the vanguard. The vanguard could launch surprise attacks and pursue fleeing enemies with the strength of an army. If they encountered stubborn resistance, the vanguard troops could quickly get support from the main force of the Hehe people. The main force escorted supplies and moved together, and a large number of prisoners of war followed the army as coolies and porters. The Hehe people liked to use dense formations when fighting, and directly pressed forward to engage in close combat, which was a standard Zulu tactic. In the 1970s, the Hehe people began to own guns. However, the Hehe people have always lacked ammunition, and the chiefs regarded guns as treasures in their hands, and only distributed them to their trusted people when needed.

In 1890, German colonists defeated the Zanzibar people and began to build fortresses in the interior of East Africa to protect trade routes. But the Hehe people continued to rob, and the German East African authorities were worried that the Hehe people would rob all the way to the sea. The German governor wanted to negotiate with the Hehe people, but before the results of the negotiations were reached, a German armed expeditionary expedition broke out in open conflict with Mukowawa.

This expedition was affiliated with the German East African Guard Force. The commander was Hauptmann von Zelewski. He was ordered to conduct a limited-scale expedition in June 1891 to pacify a local Hehe chief who plundered slaves. This Zelewski acted on his own and led his troops directly to Karenga. His troops had a total of 5 companies, each with 90 colonial native soldiers, plus three field guns and two Maxim machine guns. Next came the historic Battle of the Rugaro River in German East Africa.

At dawn on August 17, the Germans marched in long columns through a densely covered area of bushes. Cherlevsky led the army to a hill covered with rocks and thick vegetation. Apparently, he had not sent anyone to scout in advance. The field artillery and Maxim machine guns were carried by livestock, and it was said that some colonial soldiers’ rifles did not even have bullets loaded. Suddenly, a gunshot broke through the dawn, and about 3,000 Hehe warriors rushed out of the bushes, and the company that cleared the way was immediately defeated. Cherlevsky drew his gun and fired, and was immediately pierced through the back by a spear. However, the timing of this ambush was not good enough, and the Germans at the end of the team were able to organize some resistance. The expeditionary doctor and a group of colonial soldiers set up a Maxim machine gun and withstood the attack of the Hehe people until dark. The rear guard retreated to a hill and built fortifications, which allowed them to protect themselves. The Germans waited for two days, gathered the survivors, and scattered them back. Among the bodies scattered on the battlefield were 10 Germans, 250 native colonial soldiers, and about 100 porters. More than 250 Hehe people died on the spot or died of serious injuries.

The Germans were forced to temporarily switch to defense, but Mukwawa failed to seize the advantage and expand the results. Instead, he concentrated his efforts on strengthening the fortress of Kalenka to prepare for the German counterattack. The style of the Hehe people’s fortress was influenced by the Arab fortress in Zanzibar. Two generations of Hehe leaders specially sent people to the seaside to learn the Arab fortress style. According to records, the stone wall surrounding Kalenka in 1894 was 2 miles long, 8 feet high and 4 feet thick. Unfortunately, the Yaohan Fortress was not as strong as Mukowawa believed: the walls were too long and 3,000 soldiers could not defend it. Moreover, the walls were quite vulnerable to artillery fire.

The Germans later admitted that if the Hehe people had held on outside the walls, they would probably have won another great victory. However, Mukowawa did not do so. At that time, Mukowawa had the rifles seized from the Lugaro River (and a Maxim machine gun, which the Hehe people did not know how to use), but he kept them tightly to himself. When the Germans came to attack, they only distributed more than 100 weapons. It is said that Mukowawa went crazy and asked his soldiers to load blanks into their guns. He placed his hopes on magic, hoping that casting a spell on the road would stop the Germans from advancing.

In October 1894, the Germans arrived at the city of Karenga. This German army had three companies of colonial native soldiers, plus several mountain cannons. The Germans built fortifications 400 meters away from the city wall and began to bombard the wall. The bombardment lasted for two days, and then a German officer led a commando to attack the fortress. The Germans encountered only slight resistance on the city wall, but fought for four hours inside the fortress. The Hehe people fired stubbornly from the roof and the small door of the hut. One German officer and eight colonial soldiers were killed, and three Germans and 29 colonial soldiers were injured. The German commander reported that 150 Hehe people died in the battle or were burned to death in the hut. He saw with his own eyes that Mukowawa tried to ignite gunpowder in a house after being defeated, and was forcibly dragged away by his close ministers. The Germans obtained a large amount of spoils from the chief’s treasury, including gunpowder and ivory.

However, the resistance of the Hehe people did not stop. On November 6, the German army encountered an attack by more than 1,500 soldiers on the way back. The Hehe broke through the porters but were stopped by the fire of the colonial soldiers. They left many bodies behind and withdrew from the battle. In 1896, the Germans returned to Kalenga and built a fortress a few miles away in Iringa (today Iringa is an important city in southern Tanzania). The Hehe people started guerrilla warfare again, ambushing patrols and caravans and attacking villages that surrendered to the Germans. The Germans implemented a scorched earth policy to fundamentally eradicate the basis of the Hehe people’s resistance. As a result, the Germans almost captured Mukwawa several times. The scorched earth policy, coupled with the famine that swept the area, gradually destroyed the fighting spirit of the Hehe people. In July 1898, a German patrol intercepted Mukwawa’s trail near the Great Ruaha River in south-central Tanzania and tracked him all the way to his hiding place. The Hehe king was seriously ill and would rather die than surrender, so he committed suicide. With his death, the Hehe people’s resistance came to an end.

Summary

Before 1884, East Africa had not yet become a colony. Only Britain had a "treaty" with Zanzibar. Britain obtained privileges in Zanzibar under the pretext of prohibiting the slave trade and helping to train new troops. The German African Association only established a few trading posts in East Africa. Missionary forces from various countries began to infiltrate Uganda. Since the 1980s, Germany has been actively active in East Africa, and Antu has established a vast colony connecting East and West Africa north and south of the equator. Until the end of the 19th century, the two colonial powers, Britain and Germany, completed the division and sharing of East Africa. However, during this period, the people of East Africa still carried out heroic and tenacious resistance and struggle. For example, from 1888 to 1890, the Arabs and Bantu people in the German-ruled areas jointly held a major uprising and almost all the small group of colonists were expelled. The uprising threatened the interests of all colonial countries and caused joint intervention from Britain, Germany, France, Italy and other countries. Britain blockaded the coastal areas, and Germany mobilized a large army to brutally suppress the uprising.

The resistance and struggle of the East African people dealt a heavy blow to the colonial rule of the great powers and preserved the spark for the independence of the East African countries. In the 1960s, during the African independence movement, countries such as Kenya, Tanzania and Uganda gained independence one after another, formed the East African Community, and began to embark on the path of common development.