Failed political reconstruction in Afghanistan

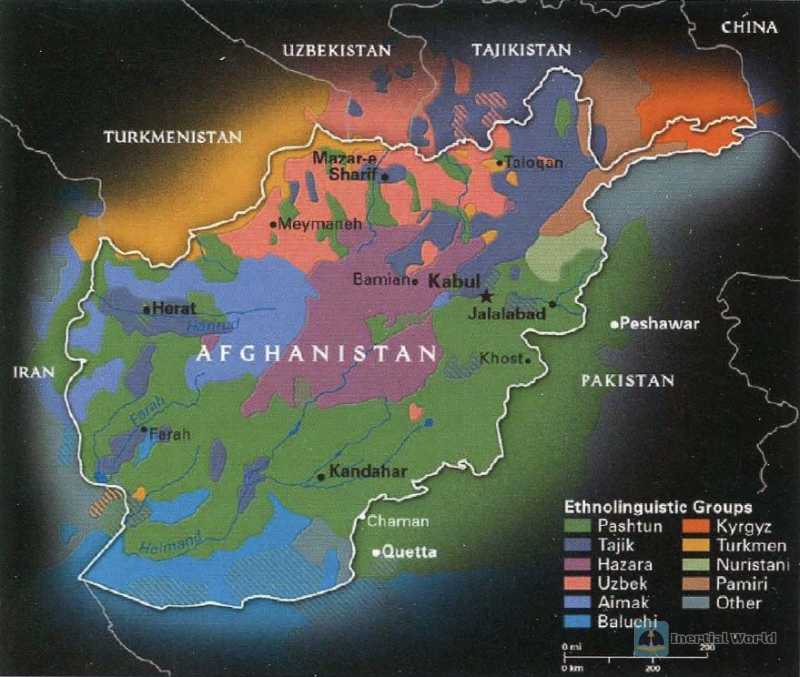

In terms of political reconstruction, in order to quickly establish a highly centralized Afghan central government, the United States supported the implementation of a presidential system in Afghanistan, despite opposition from the anti-Taliban United Front, which was composed of non-Pashtun armed forces such as the Tashk and Uzbek tribes in the north. However, this choice is incompatible with Afghanistan’s political tradition and culture. Afghanistan has never been able to establish a truly centralized system in history, let alone a democratic system in the Western sense. There are seven major ethnic groups in Afghanistan, including Pashtuns, Tajiks, Hazaras, Uzbeks, Aimaks, Turkmens and Balochs. The source of Afghans’ political loyalty is mainly ethnic and tribal connections and religious factors, and their identity recognition at the national level is very weak. There are serious gaps between different ethnic groups, tribes and sects, and the long-term civil war has caused mutual hatred and distrust, which has made it extremely difficult to promote the concentration and sharing of political power in Afghanistan. In addition, the "intractable conflict between the modern elites in Kabul and the more conservative people in rural areas" constitutes the basic political contradiction in Afghanistan. Judging from the political reconstruction promoted by the United States in Afghanistan, the US government has seriously underestimated the complexity of Afghanistan’s political transformation and stability.

In November 2001, the Bush administration promoted the United Nations to convene a meeting in Bonn, Germany, inviting Afghan politicians and representatives of relevant countries to negotiate on Afghanistan’s national political system and political development path, launching the "Bonn Process". At the meeting, the selection of Afghanistan’s basic political system and the leaders and key members of the interim government became the focus of much discussion. The United States believes that the implementation of a presidential system in Afghanistan and the establishment of a strong and centralized central government will help end the situation of numerous political factions and constant disputes in Afghanistan as soon as possible, and will also help improve the efficiency of coordination between the United States and Afghanistan. However, the Northern Alliance, which is naturally disgusted and suspicious of the centralized government, proposed that Afghanistan should implement a cabinet prime minister system to avoid the president’s monopoly leading to the excessive power of a certain ethnic group. Although the Northern Alliance and other forces oppose the rule of the Taliban regime, they are also unwilling to accept a central government dominated by the Pashtuns. To a large extent, the new Afghan government created by the "Bonn Process" has been questioned in terms of representativeness and legitimacy from the beginning, and the Pashtuns also believe that the interests of their ethnic group have not been protected in the "Bonn Process"

Thomas Barfield described the "new government established after the Bonn Conference as an arranged marriage, not free love." Even so, the Bush administration is still keen to promote the "success story" of Afghanistan’s democratization. Bush in 200 In the State of the Union address delivered in January 2004, it was stated that "the Afghan people, both men and women, are building a free, proud country that is fighting terrorism, and the United States is honored to be their friend." This optimistic description is obviously inconsistent with reality. In fact, the ruling foundation of the new Afghan government is relatively weak. Due to the lack of authority, the actual jurisdiction of the central government is relatively limited, and President Karzai is even nicknamed the "Mayor of Kabul." In the view of some Western scholars, the new Afghan government has to rely on a "network of nepotism" to maintain its political status. Steve Hayes criticized Karzai for "using his presidency, his position as a distributor of foreign aid, weapons and cash from the United States and other countries, and his status as an appointee of key government positions to build support for his rule." "Personal nepotism system"

Under such circumstances, the political contradictions between the United States and the new Afghan government have become increasingly prominent. Afghan politicians such as Karzai have repeatedly criticized the United States and other Western countries for bypassing the central government and pouring into Afghanistan in an disorderly manner. The United States accuses Afghanistan of creating a "parallel government" and government corruption. However, the Afghan people believe that the Afghan government supported by the United States is composed of greedy "Kabul elites", so they vent their anger on the United States. This contradiction has caused the United States to neither gain the favor of the Karzai government nor the support of ordinary Afghan people, which has exacerbated its difficulties in promoting political reconstruction in Afghanistan.

The so-called corruption issue has become the focus of the contradiction between the United States and Afghanistan. In 2012, the U.S. Government Accountability Office released a report stating that in the United States Of every $1 in aid funds allocated by the Agency for International Development, only 15 cents reaches the recipients, 30 cents is used by non-governmental organizations to cover the administrative costs of aid projects, and 55 cents is embezzled or abused in the links involving the local Afghan government. In the eyes of the US, corruption is a manifestation of the Afghan government’s reliance on "nepotism networks" to exercise power. In addition, in Afghan society, which emphasizes blood ties and ethnic relations, if a person becomes an official, he is considered to have the responsibility to use the power he holds to seek benefits for his family and ethnic group. Therefore, corruption has cultural and customary attributes. In order to avoid corruption, the US State Department, Agency for International Development, Department of Defense and other government agencies often bypass the Afghan central government to implement reconstruction projects on their own, and contract most of the reconstruction contracts to local warlords and strongmen. It is estimated that about one-third of external aid from the United States and other major Western countries flows into the country without the knowledge of the Afghan government. This practice caused strong dissatisfaction from Karzai. He accused the United States of causing the emergence of a "parallel government" in Afghanistan, seriously undermining the power of the Afghan central government and causing the Afghan people to have a lower degree of recognition of the government.

An estimate from 2010 to 2011 showed that about 90% of aid funds were not allocated and managed by the Afghan government, but relied on international organizations or non-governmental organizations. This restricted the Afghan government’s budget planning and implementation for domestic development, and had a negative impact on the government’s capabilities and prestige. The contradiction between the Afghan government and the United States has become increasingly fierce and public. In response to the criticism of the United States and other Western countries that there was serious fraud in the 2009 Afghan presidential election, Karzai publicly stated in fierce words that "the United States tried to manipulate the Afghan presidential election and establish a weak government in Afghanistan", "the United States has been supporting suicide bombings in Afghanistan and deliberately undermining the peace talks between the Afghan government and the Taliban", and "the United States is the root cause of various problems in Afghanistan." In this regard, some American analysts commented that "Karzai has made attacking the United States a habit" and "from the perspective of the interests of the United States and NATO, the original choice of Karzai was a huge and abnormal failure."

In April 2014, there was a crisis in the Afghan presidential election. Pashtun candidate Ashraf Ghani and Tajik Abdullah, who represented the interests of the Northern Alliance, fought fiercely. Under the mediation of then US Secretary of State John Kerry and others, the two sides finally agreed that Ghani would serve as president and Abdullah would serve as the chief executive of the Afghan government. This result shows that the United States has to accept the reality of the contradictions between Afghan political forces. The presidential system that the "Bonn Process" attempted to establish eventually evolved into a decentralized system for Pashtuns and other ethnic groups. In addition to building a national regime, local governance is also an important aspect of the United States’ political reconstruction in Afghanistan. Before the September 11th incident in 2001, Afghanistan had experienced more than 20 years of civil war. During the civil war, many warlords emerged in Afghanistan. They were mostly linked to local strongmen and illegal economic organizations, forming a political symbiotic relationship, collecting taxes and controlling trade routes, and maintaining a de facto local autonomy for many years. Whether Afghanistan can establish an effective political governance system and achieve stable development, the key lies not in the central government but in the local level, not in the city but in the rural areas. Thomas Barfield pointed out that "in 2001, the United States was worried that Afghanistan would disintegrate without a strong central government, but in 2011, it began to worry that a poorly functioning central government would also lead to disintegration." The United States gradually realized that Afghanistan’s political power needs a certain degree of "decentralization", and local governance, especially rural governance, should be the top priority.

However, in terms of improving regional governance, the United States lacks sufficient political will, as well as the corresponding resources, capabilities and leverage. After the Bush administration launched the Afghan war, although it claimed to establish a democratic system in Afghanistan, the Department of Defense, the Central Intelligence Agency and other departments have been relying on the Afghan warlords to fight against the "Al-Qaeda" organization and the Taliban, buying and supporting them, and condoning their involvement in illegal economies such as drug trafficking. The report released by the U.S. Government Accountability Office once made the following judgment: "According to the views of the U.S. State Department, the United Nations, Human Rights Watch and other international experts, the criminal acts of warlord private armed forces continue to undermine the country’s stability and hinder reconstruction. Warlords have prospered an illegal economy supported by smuggling weapons, drugs and other goods." "The United States continues to use warlord armed forces in its "counter-insurgency" operations against the Taliban, and this practice has further complicated the local situation." Due to the full focus on combating terrorist organizations and the Taliban, from 2002 to 2005, the Bush administration ignored the issue of improving local governance in Afghanistan, and the precious opportunity for Afghanistan’s political reconstruction was wasted. Local power holders have the time, space and resources to adapt the old "rules of the game" to the new situation, and "the solution of local governance issues has become more complicated and difficult than before." In addition, many people who have close ties with warlords and local strongmen were elected to the National Assembly of Afghanistan and provincial and regional councils, which means that the former can infiltrate the new political system through their agents. Later, in order to save the "nation-building" in Afghanistan, the United States began to make efforts to improve local governance. With the support of the Bush administration, the Independent Commission for Local Governance of Afghanistan was established in 2007. The Bush administration hoped that the agency would promote cooperation between the Afghan central government and local governments and non-governmental organizations, indicating that the United States began to accept a "decentralized" regime building model.

However, this failed to reverse the deterioration of local governance in Afghanistan. In 2009, Stanley McChrystal, the top commander of the US military in Afghanistan, described the phenomenon of warlords and local strongmen controlling power in his assessment report. "Some local and regional power brokers were allies in the early stages of this war, but now they are focused on controlling their respective regions. Many of them are current and former officials of the Afghan government. Their economic independence and loyal armed supporters give them autonomy, which further hinders efforts to build a unified Afghan regime. In most cases, their interests are neither consistent with the Afghan people nor with the Afghan government, which leads to conflicts that insurgent groups can take advantage of."

During the Obama administration, the United States focused on supporting the "District Service Project" initiated by the Independent Commission for Local Governance in early 2010. The project covered more than 80 key areas in the Helmand River Valley, Kandahar, Kabul, Herat, and the Baghlan-Kunduz Corridor, helping these areas improve their governance capabilities and enhance their relations with relevant departments of the Afghan central government in terms of finance and human resources. However, the actual progress of the project was very slow and later came to nothing.

As for why the local governance projects promoted by the United States are not effective, Stephen Biddle believes that the reason is that the U.S. government underestimated the political complexity of local governance and mistakenly regarded the improvement of local governance as a "non-political" process. In fact, governance issues are related to political interests, not just capacity issues. "’Capacity building’ that is not well supervised often makes the problem worse because it provides crony networks with funds and resources to reward their allies, punish their opponents, and allow crony networks to intensify their efforts to extract resources from the people. Another major challenge facing Afghanistan’s political reconstruction is how to deal with the relationship with the Taliban. Although the Taliban has lost power, it is still the main opponent of the United States in Afghanistan and has a strong political influence locally. Senior officials of the Bush administration and commanders of US troops in Afghanistan regard the Taliban and al-Qaeda as the same, but in fact there are substantial differences between the two, and the US side lacks sufficient understanding of this. The Taliban not only poses a security threat to the United States and the Afghan government, but also competes with the latter in governance. The Taliban is well aware of the political importance of rural areas, and its "comprehensive understanding of local culture, language and tribal structure" has become a major advantage compared to US troops stationed in Afghanistan.

In 2005, the report "Strategies of Insurgents and Terrorists in Afghanistan" written by Amrullah Saleh, head of the Afghan intelligence agency and director of the National Security Agency, pointed out that insecurity has led to a decline in the support of the Afghan government by local people in Afghanistan. The Taliban took advantage of this to establish "underground governments" in provinces and regions, including setting up various administrative agencies and courts to replace legal government agencies. The Taliban not only established circuit courts in many places to help people deal with complex conflicts in land and other aspects, but also conditionally allowed women to receive education and agreed to relevant organizations to implement development aid projects in areas under their control. It was not until Obama came to power that the United States began to seriously consider changing its strategy toward the Taliban, treating the Taliban differently from al-Qaeda, and treating the "diehards" and "moderates" in the Taliban differently. Under the strong promotion of Holbrooke, the special envoy for Afghanistan and Pakistan, the US top leaders began to re-understand the Taliban. In March 2009, Obama publicly stated for the first time that the United States was willing to consider talks with moderate Taliban leaders.

Under the direct promotion of the United States, the UN Security Council treated the Taliban and al-Qaeda separately on the sanctions list. In order to reflect the principle of differentiated treatment, the United States only included the "Haqqani Network" instead of the Taliban in the list of foreign terrorist organizations. The Obama administration proposed that peace talks with the Taliban must meet three prerequisites, namely, cutting off ties with al-Qaeda, stopping violent activities and recognizing the Afghan Constitution. But in fact, after 2011, the United States gradually relaxed or even gave up the prerequisites for dialogue with the Taliban.

Even so, the negotiations between the United States and the Taliban were not smooth, mainly because the US government announced the "withdrawal" time too early, and the contradictions between the United States and the Afghan government deepened, which weakened the Taliban’s willingness to negotiate. People in the US strategic community generally believe that the Obama administration’s olive branch to the Taliban while announcing the "withdrawal" timetable has a negative impact on Afghanistan’s domestic political transformation. It has not only caused dissatisfaction among the Karzai government, but also worried the Northern Alliance and other anti-Taliban forces. Under such circumstances, the trend of "armed self-protection" in Afghanistan has intensified, and local governance reform has fallen into a greater dilemma.

The failure of economic reconstruction

A stable regime needs to be based on a stable economy, and economic reconstruction is crucial to the US "nation-building" in Afghanistan. Robert Rotberg and others believe that "financial and extractive capacity" is the key to establishing a successful governance system. In short, the so-called financial capacity is to manage and use the financial funds for national development well, and distribute the benefits of economic development to the people in an appropriate manner; the so-called extractive capacity is to have the ability to build economic infrastructure and promote endogenous development. Obviously, the US economic reconstruction in Afghanistan has failed to enable the Afghan government to acquire these capabilities, and Afghanistan’s weak economy and extreme poverty are very prominent.

Due to the hasty launch of the Afghan war, the Bush administration did not make a clear plan on how to restore the domestic economic order of Afghanistan as soon as possible after overthrowing the Taliban regime. It basically pushed the task of coordinating Afghanistan’s economic reconstruction to the United Nations. Compared with the expenditure on the Afghan war, the United States’ investment in economic reconstruction is quite limited. In addition, the aid from the United States and other Western countries has the problem of "focusing on promises and neglecting fulfillment". According to statistics from the Ministry of Finance of the Afghan government, less than 40% of the donations were made from 2002 to 2011. Among them, the United States is the largest donor to Afghanistan’s reconstruction, and about 1/3 of the aid funds come from the United States. However, the United States promised to provide $22.8 billion in aid, but only about $5 billion was actually fulfilled. Among the aid funds fulfilled, the proportion received by the Afghan central government is relatively low. From 2002 to 2008, the Afghan government only received 20% of the total aid funds fulfilled by donors.

The Afghan government also faces many restrictions from the United States on the use of reconstruction aid funds. The main legal basis for the United States to provide economic assistance to Afghanistan is the Afghanistan Freedom Support Act passed in December 2002, which proposed to provide Afghanistan with $3.7 billion in civilian assistance in fiscal years 2003 to 2006. Among them, $425 million is allocated annually to meet humanitarian needs and promote development, and $15 million is allocated annually for anti-drug operations. In particular, the US Congress has set many "thresholds" for the allocation of aid funds to Afghanistan, such as requiring the Afghan government to meet certain standards in maintaining women’s rights and developing human rights, fighting corruption, and holding fair and free elections.

The United States mainly inputs aid funds to Afghanistan through channels such as the Economic Support Fund and the Afghanistan Infrastructure Fund. The United States Agency for International Development is the main user of aid funds, and the US Department of Defense also leads the use of many aid funds and has established relevant project promotion agencies, including the Afghanistan Infrastructure Fund and the "Business and Stability Action Group". Another important channel for the United States to provide aid to Afghanistan is international organizations, among which the World Bank and the Asian Development Bank are the main cooperative institutions. In May 2002, the World Bank re-established an office in Afghanistan after 20 years, and established the Afghanistan Reconstruction Trust Fund in 2003. With the support of the United States, the Asian Development Bank has played an important role in the construction of roads, railways, power grids and other infrastructure in Afghanistan. The United States provides economic reconstruction assistance to Afghanistan in two main ways, namely "targeting Afghan government agencies and state-owned enterprises" and "targeting the project itself." A typical case is that the United States provides support to the National Solidarity Project operated by the Afghan government through the Afghanistan Reconstruction Trust Fund. The main goal of the project is to promote local development in Afghanistan and help more than 20,000 villages and towns build priority development projects determined by local community development councils. Each project can receive a maximum of $60,000 in funding. The United States provides more than 90% of the funds for the implementation of the project.

However, the results of Afghanistan’s economic reconstruction are very limited, and the ability of governments at all levels to absorb tax resources, meet the economic needs of the people, and promote the country’s endogenous development is very weak. Several mistakes made by the United States are important factors leading to this result. In order to serve military goals such as "counter-terrorism", the United States attaches importance to "quick effect projects" and ignores Afghanistan’s long-term development needs, and attaches importance to cities and ignores rural areas. Agriculture is an important foundation for the sustainable development of Afghanistan’s economy, but the United States’ support for Afghanistan’s agricultural development is seriously insufficient, and it has failed to provide sufficient development assistance to rural areas of Afghanistan. From 2001 to 2011, only $400 million to $500 million of international aid funds went into the agricultural sector, and less than 5% of the aid funds from the United States went to Afghanistan’s agricultural development, while 66% of the funds went to military security and road construction. In Badakhshan Province in northeastern Afghanistan, most of its 830,000 people rely on agriculture for their livelihoods, but in 2009 the province’s budget for agriculture, irrigation and animal husbandry was only $40,000, roughly equivalent to one to two months’ salary for foreign consultants in Kabul. In addition, less war-torn provinces such as Bamiyan Province have been neglected, and 80% of the aid from the United States and other countries has mostly flowed into Helmand Province and other southern and eastern provinces to support the US military and NATO coalition forces in carrying out military operations in these areas. Under such circumstances, the Afghan economy has become a typical "garrison economy", and economic growth is heavily dependent on the activities of foreign troops such as the US military in Afghanistan. Most of the economic aid from the United States to Afghanistan flows to areas closely related to military activities. The primary purpose of this type of aid is not to promote the development of Afghanistan, but to make the military operations of the US military more convenient, which has led to strong dissatisfaction among the Afghan people. In addition, since the US military and NATO coalition forces often participate in some infrastructure reconstruction projects, these projects are more likely to become targets of harassment by insurgents. The deterioration of the security environment has made economic reconstruction more difficult to carry out.

Being ignored, 80% of the aid from the United States and other countries mostly flowed into Helmand Province and other southern and eastern provinces to support the military operations of the US military and NATO coalition forces in these areas.

Under such circumstances, the Afghan economy has become a typical "garrison economy", and economic growth is heavily dependent on the activities of foreign troops such as the US military in Afghanistan. Most of the US economic aid to Afghanistan flows to areas closely related to military activities. The primary purpose of such aid is not to promote the development of Afghanistan, but to make the US military operations more convenient, which has led to strong dissatisfaction among the Afghan people. In addition, since the US military and NATO coalition forces often participate in some infrastructure reconstruction projects, these projects are more likely to become targets of harassment by insurgents. The deterioration of the security environment has made economic reconstruction more difficult to carry out.

The economic reconstruction of the United States in Afghanistan is highly dependent on domestic contractors and non-governmental organizations, which has created a "double parasitic system". On the one hand, the massive influx of international aid has turned Afghanistan into a "parasitic country". On the other hand, the reconstruction funds have flowed back to the United States in the form of US companies and aid organizations contracting US government projects, and relevant US institutions have also become "parasites". Many Afghans complain that what the United States gives is nothing more than an invisible and intangible "phantom aid". According to statistics from the non-governmental organization "Action Aid", 83% of US aid to Afghanistan has become "phantom aid". These aid funds either flow back to the United States or are used ineffectively and cannot bring benefits to the Afghan people.

Government agencies such as the United States Agency for International Development directly signed contracts with many American contractors. Most of these contractors set up headquarters in Washington and strived for the US government’s aid contracts through public relations activities. They were considered "Washington thieves." US congressmen helped these contractors get government contracts in exchange for the latter’s support in campaign donations and other aspects. "The evidence of the connection between obtaining contracts and political donations shows that contracts are not complete. A large amount of US aid funds were obtained through competition." The funds were spent on paying salaries to various consultants in the United States and foreigners working in Afghanistan, as well as subcontracting to other companies, hiring private security personnel, and renting luxury houses in the local area. These practices have greatly increased the cost of economic reconstruction projects. Michael Hogan and others believe that this is actually a "government-supported corporate crime" and "higher-level unethical behavior."

The United States lacks effective measures to deal with Afghanistan’s drug economy. Due to the harsh natural conditions and long-term war, drug production and trafficking have become the way of livelihood for many Afghans, and the drug economy has formed a symbiotic relationship with other economies. Karzai regards the drug problem as the most serious problem since the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan in 1979, which is more serious than terrorism. Since the United States lacks a deep understanding of the "pathology" of the "cancer" drug economy that is more harmful to Afghanistan, its anti-drug policy has been either short-sighted or unrealistic, from the focus on "eradicating poppy cultivation" during the Bush administration to the emphasis on "alternative planting" during the Obama administration. After the outbreak of the Afghan war, the Bush administration was reluctant to send a large number of troops to Afghanistan. When the United States carried out its "anti-terrorism" mission, it had to rely on local warlords and local strongmen in Afghanistan, who regarded drug production and trafficking as their basic source of funds and strength guarantee.

In 2004, the Bush administration began to pay attention to the drug problem in Afghanistan, but attributed the worsening of the problem to the failure of the "leading countries" responsible for dealing with the drug economy, Britain and the Karzai government, to vigorously eradicate poppy cultivation. The United States forced the Karzai government to implement a policy of eradicating poppy cultivation, which caused political turmoil. Many Afghans lost their livelihoods and became landless farmers or tenants who planted poppies. Many people could not bear the hardship and fled to the border areas of Afghanistan and Pakistan and joined the rebel organizations.

The Obama administration proposed "excellent performance initiatives" and promised to provide financial rewards to provinces that successfully reduced poppy cultivation, trying to help Afghan farmers gradually get rid of their dependence on the drug economy by promoting alternative planting. However, alternative planting requires supporting policies to promote agricultural development, such as building Or improve the infrastructure such as irrigation system, provide fertilizer and improved seeds, help farmers find domestic and foreign markets, develop rural finance, etc. The United States lacks investment in these aspects, so it is naturally difficult to carry out alternative planting. According to statistics from the Afghan government, in 2011, about 191,500 farmers relied on poppy cultivation as their main source of livelihood. Among the villages surveyed, only 30% of farmers received assistance in seeds, fertilizers and irrigation in the previous year. Most families chose to replant poppies. With the announcement of the gradual withdrawal of troops from Afghanistan by the United States, Afghanistan’s drug economy problem has become more serious. The survey results of the United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime show that the area of poppy cultivation in Afghanistan reached 209,000 hectares in 2013, an increase of 36% over 2012, a record high. The annual opium production was 5,500 tons, an increase of 49% over the previous year.

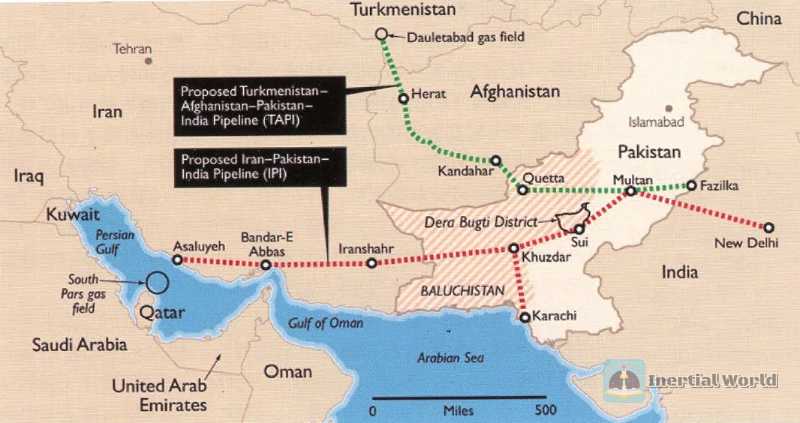

The "New Silk Road" plan proposed by the United States has not been effective, and it is difficult to form endogenous development momentum in Afghanistan. In the case of ineffective response to issues such as the drug economy, the United States seeks to add external impetus to Afghanistan’s economic reconstruction. In September 2011, then Secretary of State Hillary Clinton proposed the "New Silk Road" plan, which aims to take advantage of Afghanistan’s geographical location and build Afghanistan into a regional trade and transportation hub to promote economic integration in Central Asia and South Asia. The United States originally hoped to provide impetus for Afghanistan’s development through the "New Silk Road" plan, but it overestimated the integration of Central Asia and Afghanistan in terms of geo-economics and did not invest. In addition, although the United States supports the natural gas pipeline project connecting Turkmenistan, Afghanistan, Pakistan and India, it obstructs the natural gas pipeline project between Iran, Pakistan and India. The United States pressured India to withdraw through civil nuclear energy cooperation, and then asked Pakistan to abandon the project. This "double standard" for regional economic integration has caused dissatisfaction among relevant countries.

At the same time, there is still a lack of internal motivation in Afghanistan to promote the "New Silk Road" plan. The expected economic benefits brought to Afghanistan by the "New Silk Road" plan are mostly given to large cities such as Kabul, and the vast rural areas are unlikely to benefit. The United States also tried to use the "New Silk Road" plan as a geopolitical tool. Erica Mallett pointed out that "the ’New Silk Road’ plan unnecessarily geopoliticizes typical trade policies, which deliberately exclude Russia, China and Iran." Frey, the proposer of the "New Silk Road" concept. Derek Starr pointed out that the reason why this concept was taken seriously by the US government around 2011 was mainly because it hoped to share the responsibility of Afghanistan’s reconstruction with the international community in the context of the US withdrawal. However, the US State Department has unnecessarily politicized this economic concept, and has been overly vigilant and even excluded Russia.

The "New Silk Road" plan lacks substantial progress in practice, and it is difficult for the Afghan economy to truly benefit from the plan. Katherine Collins concluded that "Washington proposed the ’New Silk Road’ plan to help Afghanistan get rid of poverty and bring stability to the region. This idea is attractive, but it is a daydream."

From 2001 to 2014, with the support of the United States and other countries, Afghanistan’s reconstruction has made certain progress in political, economic and social development, but Afghanistan’s "national capacity, including infrastructure construction capacity, economic transformation capacity, distribution capacity, and ability to coordinate relations with external actors, is still quite low. Afghanistan has not become the free and democratic country that the Bush administration tried to establish, and the Taliban, who were driven out of Kabul by the United States, have controlled most of Afghanistan in 2021 and returned to power after the withdrawal of US troops. The US experience in Afghanistan once again proves that the US intervention in small countries often fails. Failure. Mearsheimer pointed out that "despite the great efforts of the US military and the investment in reconstruction that has exceeded the Marshall Plan’s commitment to Europe after World War II, the United States is doomed to fail in Afghanistan."

The failure of the United States in the graveyard of empires

The "nation-building" carried out by the United States in Afghanistan lacks feasible goals and a coherent and clear strategy. Many policies are contradictory, resource investment is seriously insufficient, and there are many problems in policy implementation. The victory of the United States in overthrowing the Taliban regime in Afghanistan is nothing more than a "catastrophic success" and the "Afghan version of the American dream" is unsustainable. The failure of the United States’ "nation-building" in Afghanistan is reflected at the strategic level in "the United States’ serious lack of understanding of the country it intervenes in", from "light footprint" to "increased investment" From the "quick withdrawal" to the "rapid withdrawal", this ups and downs of policy changes show that the United States does not have a well-thought-out, coherent and clear strategic design on the Afghan issue.

The Iraq War launched in 2003 and the "freedom agenda" of the Bush administration to implement democratic transformation in the Greater Middle East have further plunged the US "nation-building" in Afghanistan into "drifting". Although the United States was able to achieve military victory in the early stages of the Afghan war, it lacked an effective political strategy to deal with the Afghan issue, especially making the mistake of indiscriminately attacking the Taliban and al-Qaeda. To a large extent, this is due to the fact that the US decision-makers and policy implementation levels know very little about Afghanistan, especially its "power structure, customs and mental state". The United States "lacks cultural affinity between the people of the countries it intervenes in, and has no understanding of the local "There is no sufficient understanding of the mentality and environment of the locals."

As a witness to the promotion of "nation-building" in Afghanistan, Dav Zhakshim reflected that "as long as Americans ignore the real concern for the ’locals’, as long as they do not understand the culture, lifestyle and values of the locals around them, not to mention the language, the United States will never be able to achieve its policy goals in a non-Western environment." The fundamental reason for this situation is that the United States lacks real respect for Afghanistan’s sovereignty and its disregard for the interests of the Afghan people. The United States mainly pursues its own security interests in Afghanistan. In the eyes of most Afghans, the United States is an unwelcome "external force" or even an "aggressor."

The United States’ "nation-building" overseas is deeply influenced by domestic political factors in the United States. Since the Clinton administration’s "nation-building" in Kosovo and other places caused dissatisfaction at home, the Bush administration showed a reluctant attitude towards "nation-building" in Afghanistan from the beginning. However, in order to win the support of the American people for the Afghan war, Bush Jr. and Condoleezza Rice and others continued to promote the so-called "wonderful success story" of Afghanistan, but the price they paid was the loss of the "golden opportunity" to start reconstruction after the main combat mission in Afghanistan was completed.

During Obama’s administration, Afghanistan policy became an arena for the "Obama circle" and the Department of Defense, the State Department and other parties to wrestle. The contradictions between the White House and military leaders continued to deepen. Even Holbrooke, the special envoy for Afghanistan and Pakistan, was not trusted by the White House. As the saying goes, "the White House is more interested in getting Holbrooke out of office than implementing the right policy." This power game has a great impact on the US Afghanistan policy, causing the Obama administration to frequently replace the commander of the US troops in Afghanistan, and announced the "withdrawal" timetable while announcing the "increase of troops." Although this is unwise in terms of Afghanistan strategy, it meets the need to establish the authority of the White House and gain political support from domestic voters. As early as 2009, Obama realized that the American people’s support for the Afghan war and reconstruction would not last long.

Although the United States is reluctant to "build a nation" in Afghanistan, there is no lack of ideas to impose its own interests and political ideas on Afghanistan. For example, in policy areas such as women’s issues, the United States’ approach is divorced from the reality of Afghanistan and violates Afghan social and cultural customs, and is more to respond to domestic demands. This "imposed liberal values" and "Western cultural invasion" have caused dissatisfaction among the Afghan people.

Finally, the United States’ "nation-building" in Afghanistan faces serious shortages in personnel, resources and mechanisms. The "capacity deficit" is an important factor that makes the US "liberal hegemony" strategy unsustainable. Although the United States has carried out many "nation-building" actions since World War II, the United States lacks the ability of "institutional learning". It seems that it has to start over every time and cannot learn lessons from previous mistakes. In promoting Afghanistan’s "nation-building", the United States faces old problems such as unsustainable resource investment, poor military-political coordination, and poor cooperation among civil institutions. It also has to face new difficulties in carrying out reconstruction operations in an Islamic country and in a divided ethnic and social environment. In this process, the United States has fully exposed the problems of frequent transfers of senior military and political officials, short terms of service of diplomats, serious "risk aversion", insufficient civil aid personnel, poor intelligence work on Afghanistan, and reconstruction projects that are eager for quick success and lack supervision.

"Nation-building" as a large-scale "social engineering" for intervening in the country is an extremely complex task. Its core challenge lies in dealing with the problem of "interconnection between security and development". In theory, it requires the United States to use diplomatic, military and development policy tools in a comprehensive and balanced manner to establish an effective "whole-government" action framework, but the practice of the United States in Afghanistan has proved that it is quite difficult to truly achieve this goal.

"Nation-building" must be a political process, not just a problem of mechanism, technology or capacity. Fundamentally speaking, the United States’ "nation-building" to reshape Afghanistan based on its own interests and its own wishes and preferences lacks a moral basis and is difficult to obtain the real support of the Afghan people. There are many conflicts with the reconciliation process advocated by the Afghan government, which is "led by Afghans and owned by Afghans", highlighting the arrogance of American power and the profound dilemma of its "liberal hegemony" strategy. The United States’ "nation-building" in Afghanistan was once highly anticipated. Larry Goodson proposed in 2003 that "if the United States can persist in Afghanistan, Afghanistan can provide a ’demonstration effect’ to show that even those Islamic countries with extremely unfavorable conditions can achieve good governance, economic development and establish friendly relations with the West."

However, from a realistic point of view, the United States’ "nation-building" in Afghanistan has failed, let alone played a "demonstration effect". As Amitai Etzioni said, "nation-building" driven by external forces is very costly, but basically will not succeed. The COVID-19 pandemic in 2020 plunged the United States into a deeper crisis, further reducing the impulse of American society to interfere overseas. The Biden administration’s rapid withdrawal from Afghanistan shows that it is unwilling to bear the heavy burden of "nation-building" again. (To be continued)